Hankering for rural contact? Pahela Baishakh isn’t the answer

It's been quite some time since we've had a Pahela Baishakh in the middle of Ramadan. Their convergence this year begs appreciation of life in its many complexities but also raises questions. How do you, for example, reconcile the spirit of restraint of the holy month with the unrestrained joy of life associated with Bangla New Year? For now, perhaps we should be just happy that the familiar sights and sounds of Pahela Baishakh festivities are back. The celebratory mood at the historic Ramna Batamul is not only a nod to tradition but also a welcome sight after two years of pandemic-induced closures, during which we lost more than just music. It means turning a page filled with loss and grief, and giving life a fresh start after it has been rudely stopped in its tracks.

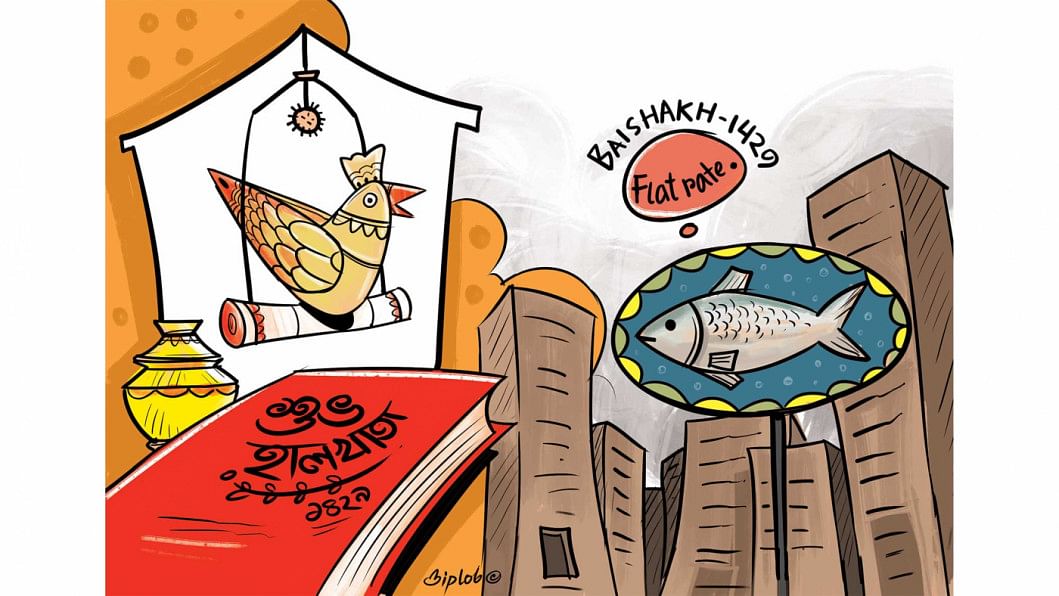

Chhayanaut's musical tribute to Pahela Baishakh, or the spectacles of the Unesco-recognised Mongol Shobhajatra, can be equally evocative for those who see in them a celebration of nature and the pastoral life. But here's the irony: How out of place does this celebration seem when held in a concrete mess like Dhaka? Put another way, we're celebrating the rural idyll and tradition through nature-themed songs and processions featuring traditional artefacts, carnival floats and other folk motifs, all the while surrounded by flyovers, skyscrapers, shopping malls and endless streams of vehicles. In truth, it's more lamentation than celebration. One of the conundrums of our search for a closer connection to the rural world is that the search itself has morphed into a "fancification" of those rustic products and motifs now on display at the festival sites. It's as if the visitors are customers, and what they are really buying into is a sort of processed pastoral.

Dhaka is a city that is not only increasingly encroaching upon the nearby countryside, but also snubbing out all traces of rustic life and values within itself. I say "values" because taking in the scene without taking in what it represents is superficial. Dhaka's urbanisation is in sharp contrast to the ruralisation drive in some more developed parts of the world. I remember reading about the ruralisation trend in the UK, where the desire for a closer connection with nature has led to a replication of the countryside in a number of cities and towns—in how their residents shop, eat, play, read, dress, decorate homes, and even spend their time. You can see rustic playgrounds, wildflower meadows nestling beside tower blocks, rustic furniture, weekly farmers' markets, flourishing rural children's literature, street food being sold out of revamped agricultural trucks, or from village-delivery-style bicycles. Pastoral scenes, real or manufactured, are everywhere. There is a deliberate attempt by ordinary citizens to bring the best part of the country into their lives.

One may argue if this is enough for someone seeking true rural contact, or possible in a city like Dhaka. But we are not even giving it a serious thought anymore, let alone a serious try, apart from having Pahela Baishakh celebrations. As I remarked elsewhere, "Dhaka is trapped in an ironic twist as it grows and falls apart at the same time. Its aggressive development is rivalled only by the progressive decline in almost all other parameters of urban life." Any description of this city these days invariably summons up images of toxic air, loud noise, unsafe drinking water, traffic gridlocks, high population density, high cost of living, inadequate road, transport and recreational facilities, general lack of security, etc.

More than the decline in the quality of our sights and scenes, it's the absence of rural values and the essential simpleness associated with them that should bother seekers of rural contact. Imagine strolling down the street and not being stopped for a salaam or namaskar. Imagine not knowing your next-door neighbour. Imagine not having any meaningful contact with your children or parents. Imagine not being on a first-name basis with anyone outside family or friends. Imagine feeling restless every time you go out, or get on a public transport, anticipating trouble. Imagine feeling lonely even when surrounded by people. Imagine worrying if you'd have a final resting place somewhere you know, or have anyone beyond close relatives at your janaza prayer when you die. This lack of connection and simpleness is the opposite of what living—or dying—means in the countryside, at least the villages I visited.

I got a real taste of that recently after attending the janaza of a relative. He was by no means a popular man—just someone who lived long enough, albeit weakened by infirmity. But his janaza was attended by almost the whole neighbourhood. Relatives close and distant, neighbours from adjacent villages and even random people who were passing by at the moment felt the need to give him a proper send-off. Memories were shared, tributes offered, and prayers sought. His body, after the janaza, was carried to the gravesite and laid to rest among the people he once knew. As the poet Lang Leav said, "We will remain unwritten through history, no X will mark us on the map; but in books of prose and poetry, you loved me once, in a paragraph." My uncle would remain similarly unknown in history, but his stories will survive through the people he was connected with.

I have often marvelled at these rural customs, values and the power of stories shared and passed through generations. To me, the countryside is more than the purity of its water, cleanliness of its air, or the unadulterated nature. Living in Dhaka as we now do, bereft of any real connection with it or the people around us, what we need is a critical rethink of our desire for rural contact and how we want to achieve it. We must make a conscious effort to turn the clock back on Dhaka's destructive urbanism, and begin a gradual process of ruralism, covering not just the sights and sounds but also the values that can make us live better. Celebrating Pahela Baishakh is not the answer to the void we feel deep inside.

Badiuzzaman Bay is an assistant editor at The Daily Star.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments