The longstanding fascination with Regency romance

I know it says 'romance' in the title but you're going to have to take my word for it when I tell you that romance is my least favourite genre in literature. It took me several months to go through the Shakespearean classic, Romeo & Juliet, simply because I kept getting too bored to continue reading it in one sitting. Any attempts to read a Nicholas Sparks novel have only resulted in my either dozing off or flipping through to the last chapter to see how the story ended.

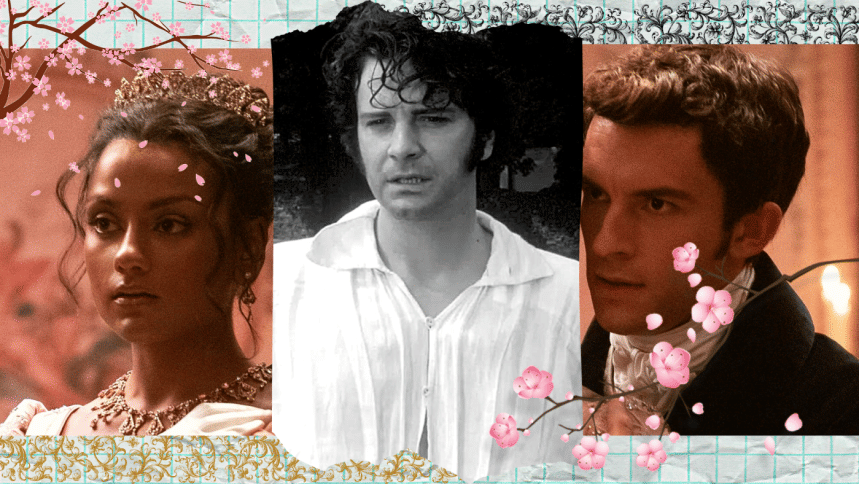

But I eventually came to make an exception for Jane Austen's Pride and Prejudice, Julia Quinn's Bridgerton series (Avon, 2004-2006), Meg Cabot's Nicola and the Viscount (HarperTeen, 2004), and soon enough, romances inspired by the high society of the British Regency period.

The real question is this: how is it that the privileged lives of the British upper classes, in a period of time which lasted arguably less than a decade, have managed to leave behind such an impressive legacy in English literature?

One would most likely credit Jane Austen's literary works being responsible for the birth of fictional romances set during the Regency era. One would be partially correct. While it is indeed Austen who penned some of the earliest and most iconic Regency-era romances, stories such as Pride and Prejudice, Persuasion and Emma, it is novelist Georgette Heyer who helped popularise the 'Regency romance' subgenre early in the 20th century, with her works heavily borrowing elements from those of Austen's. The appeal for the literary subgenre saw a steep decline at the turn of the 20th century, with readers focusing their attention on the broader genre of historical romances. Regency romances went on to gain momentum once again post the 2010s, with contemporary authors Martha Waters, Vanessa Riley, and Evie Dunmore breathing new life into the subgenre by introducing modern ideas and concepts against a backdrop of traditional settings. In the present day, the traditional aspects of a Regency romance—the sexist and racist undertones—are often abandoned or steered in favour of more modern perspectives, in order to appeal to a contemporary audience.

The stories, though, almost always start out as a complicated and heavily-charged heteronormative love story set in the years between 1811 to 1820. These days contemporary novelists have subjected this classic storyline to various treatments of their own, modernising the subgenre over time. But there's much more to a Regency romance.

Its true appeal lies in its ability to offer absolute escapism, in the form of a period romance rife with nearly-endless drama. In the fictional world of Regency romances, there are always balls to attend and weddings to plan, with whispers of an ensuing scandal around every corner. Days consist largely of daily promenades or carriage rides, and elegant dinner parties.

In the midst of all this, the romance between the protagonists plays out like a slow burn through heated banters and stolen glances across ballrooms and dining halls. What starts out as a battle of words between two equally headstrong individuals, always concludes in an almost fairytale-like happy ending. These tales carry none of the period's harsh reality—the squalor and poverty in communities outside of the court's circle, the stark class and racial inequalities—while also reflecting the booming popularity at the time of "fashionable novels" which portrayed the upper classes in all their glamour. This is what truly draws a reader in, the opportunity to take fictionalised accounts of the lives of a select few for what they are: thoroughly entertaining works of fiction, and nothing more.

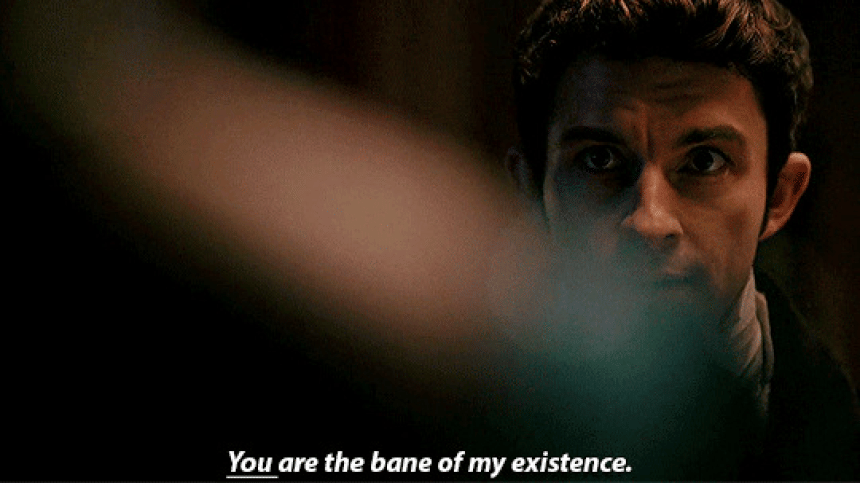

The romantic tension in these stories doesn't stem from 'love at first sight', but rather 'intense dislike at first sight'. A Regency romance believes in finding a match between two people who intellectually challenge each other instead of sharing the same opinions on everything. The couple find their way to love in reverse. This allows the plot to explore the underlying passion in disliking an individual, and what might become of such intense emotions. The reader thus witnesses love between protagonists expressed less through physical contact and more through subtle gestures: a sudden moment of breathlessness, fingertips brushing, a longing gaze. There is something beautifully poetic about the idea of love being communicated entirely through little actions bound to go unnoticed.

Rasha Jameel studies microbiology whilst pursuing her passion for writing. Reach her at [email protected].

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments