Floral economy of Bengal

During the Mughal period, gardens were a ubiquitous element of the city landscape. Dhaka, once capital of the Bengal Subah, was no exception, and the names of some areas of the city such as Shahbag, Lalbag, Golapbag, Malibag, Malitola and Fulbaria bear testimony to this heritage. There are also numerous historical references to the widespread cultivation of various types of flowers in Bengal.

We find interesting details about an exceptional flower of Bengal and the fragrance prepared from it in the book titled Travels of Fray Sebastien Manrique (1629-1643). However, the author does not mention the name of the flower. He informs that this flower used to be cultivated in Medinipur. Oil could be made from it. It was also exported to different states.

James Taylor wrote in details about safflower cultivation in Dhaka in his book 'A Sketch of the Topography & Statistics of Dacca' (1840). He noted, "The Dacca safflower, however, is superior to any that is grown in India, and ranks next to China safflower in the London market."

During the 1860s, James Wise was the Civil Surgeon of Dhaka. His book, 'Notes on the Races, Castes and Trades of Eastern Bengal,' published in 1883, provides a detailed account of the types of flowers available in the area and the activities of gardeners in the nineteenth century. The author shares that there were numerous Muslim gardeners in Dhaka during this period. They used to nurture flower seedlings and sell them in the market. They were involved in the production of different varieties of Jasmine, Royal Jasmine, Arabian Jasmine, Marigold and Rose Saplings. Besides, they used to fashion diverse kinds of flower garlands, flower bracelets and flower sticks for Muslim women to use. Bouquets of flowers were highly regarded by aristocratic Muslims. Flowers were offered at the shrines of the saints.

There were also Hindu Malakars (makers and sellers of garlands). They were known for decorating houses, shops and boats with flowers. They used to supply flowers to temples. Special flowers such as Champak, Royal Jasmine, Arabian Jasmine and Gandharaj were offered to specific god and goddesses in Puja. Garlands made by anyone other than Malakars were not considered sacred. The Malakars were also entrusted with tying the chignons of brides. Arabian Jasmine and Rose were the customary components of chignons.

Shri Jatindra Mohan Roy, in his book 'History of Dhaka (Volume 1)' (1912), provides a long list of flowers that were produced in Dhaka during that period: Marigold, Jasmine, Arabian Jasmine, Malati, Butterfly Pea, China Rose (white and red), Spanish Cherry, Champak, Rotunda, Golden Champak, Giant Calotrope, Oleander (blood red and white), Fringed Rosemallow, Lotus, Philippine Violet, Bhat, Tuni, Hazra, Nandadulal and Crape Jasmine.

The fact that the flower trade did not flourish in India at the beginning of the twentieth century can be inferred from 'Fuler Mulyo' (The Price of Flowers), written by Prabhat Kumar Mukherjee. It was published in 1904. The main character of the story is Maggie, a poor British teenage girl. When she gave the writer a shilling for offering a floral tribute at his brother's grave in India, the writer's soliloquy read: I thought I would return this hard-earned shilling of the girl. I said, "Flowers are available in abundance in our country, you don't have to buy them with money."

The flower industry gained momentum during the British period through the importation of foreign flowers from England and other countries, the establishment of organizations such as the Calcutta Botanical Garden and the Agriculture Society Calcutta and the collection of local flowers from different regions. Kamini, kanchan and gandharaj blossomed alongside the exquisite and colorful seasonal British flowers.

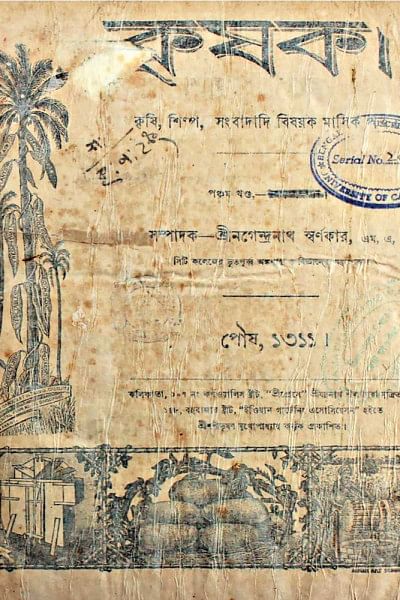

Miscellaneous features related to the cultivation, marketing and usage of flowers in Bengal can be gleaned from various agricultural periodicals published from the region. The pictorial monthly, Krishi-Samachar, was published under the editorship of Shri Nishikanta Ghosh. It had its office in Dhaka. Later, the journal was renamed 'Krishi-Sampad.' Another magazine titled 'Krishikatha' used to be published from Faridpur during the same period. Examples of other agricultural periodicals include Bhumilakshmi (Birbhum), Prakriti (Kolkata) and Krishak (Kolkata). One of the recurring topics in these magazines was rose cultivation. Relevant magazines contained instructions on how to nurture rose plants and apply fertilizers.

A news item titled 'Rose Flower Fair' was published in Krishak on January 31, 1901. The fair was held at Alipore Garden. In another issue of the magazine, a report was published on a flower show which was held in Shillong in 1905. Medals and prizes were distributed at the flower fair. The curiosity of the people was so great that about 240 people bought tickets for this exhibition. A wide array of gardening instruments was displayed there. In those days, rows of fruits and vegetables also made appearances at flower exhibitions. Additionally, new and rare trees were also exhibited. The Gorer Math of Kolkata was the designated space for many such flower fairs.

An old issue of 'Krishak,' published in 1911, contains some interesting facts about the sales of flowers. In Kolkata, flowers like China Rose, Gandharaj, Chrysanthemum, Marigold, Ground Lotus, Lotus and Champak used to be sold at a great number of temples. Profits from selling flowers were generally good. The main location for selling Arabian Jasmine and Jasmine flowers was Mechuabazar, which later came to be known as Jorasanko. Gardeners and wholesalers used to purchase flowers through arrangements with garden owners. These flowers would then be sold to buyers on the street.

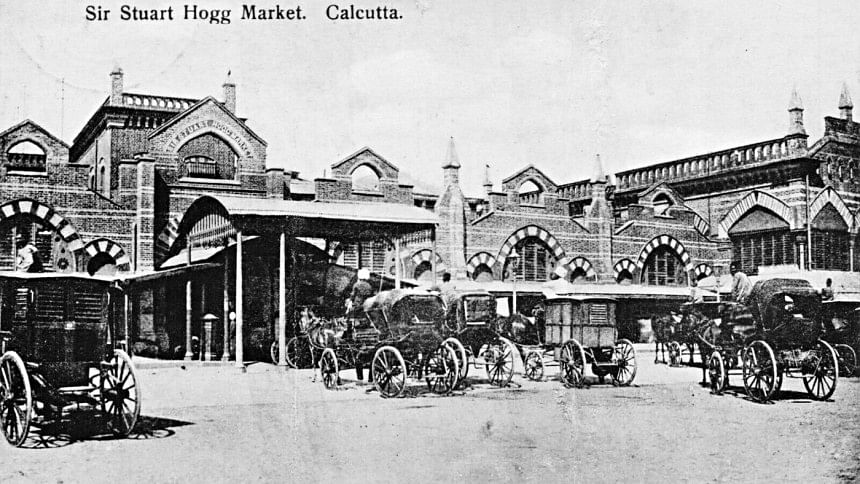

As the Falgun season embarked, Arabian Jasmine would be sold for six to eight rupees per seer. Saheber Bazaar was the locality where Rose, Tuberose, White Champak, Magnolia and British seasonal flowers were sold. The market was named after Stuart Hogg, the then chairperson of the Kolkata Corporation. Although its official name was Stuart Hogg Market, it was renamed as 'New Market,' and came to be known as such to the people of Calcutta.

An organisation named 'Krishi Bagicha Samiti' was established with the aim of improving the cultivation of fruits, flowers and vegetables. The institution undertook research projects in collaboration with local and foreign experts.

Alkananda Patel's autobiography, 'Prithibir Pothe Hetey,' provides an account of flower gardens in Dhaka in the 1930s and 1940s. She writes, "My first memory revolves around House no. 5 of Purana Paltan. The quiet neighborhood. Houses were mostly single storied with a lot of land. In addition to Star Jasmine, White Garland-Lily, Hiptage, Jasmine and Dwarf White Bauhinia, many houses had seasonal flower gardens. My father was passionate about gardening. He would measure the diameter of the chrysanthemum. Even in his last days, he would write to us enthusiastically, describing sizes of flowers. Many people brought seeds from overseas and planted foreign flowers to fulfill their hobby of gardening. At House No. 5, during the winter season, the creeper of the Sweet Pea flower climbed the bamboo as the smaller flowers flickered and stared.''

"Nasturtium, Phlox and Petunia spread the blended fragrances. Besides, there were flowers such as Marigold, Crape Jasmine, Red Rose, China Rose, Double Petal Hibiscus, Tuberose, Arabian Jasmine, Star Jasmine and Dwarf White Bauhinia. Some of my favorite sights were bunches of Hiptages, Wild Passions and Night-Blooming Jasmines scattered on the green grass. The Night-Blooming Jasmine makes one reminiscent of the soft, golden sun of autumn and the reverberations of the drums of Durga Puja - the call of festival and joy. Most of the houses within the vicinity of the university had beautiful gardens. The garden of Nilkhet was famous. Professor Satyen Bose's garden, where he used to take strolls, was well-known. Even though gardeners were pivotal, it was more often than not the householder who enhanced the beauty of gardens - that was the perspective of my father."

Speaking of Dhaka, Mohammad Abdul Qayyum shares in his book, 'History, Tradition and Culture of Dhaka,' that the use of flowers on the occasion of marriages was common. A Dala used to be sent from the groom's house to the bride's residence. The basket was made of raw jackfruit leaves and contained garlands, bangles and flower chains for the bride. However, no large-scale flower cultivation existed back then and flower shops were also not widespread. Malakars were available at Chawkbazar and Shankhari Bazar, where they had opened their own flower stalls.

Mizanur Rahman, in his book 'Dhaka Puran,' refers to another flower market which was located near Babubazar outpost. The buyers were mainly those who were traveling to Kumartuli. Some buyers would gift their purchases to sex workers.

Syed Ali Ahsan writes in his book 'Sixty Years Ago Dhaka' that large, red roses used to be sold outside the gates of the Baldha Garden early in the morning. There were around 200 varieties of roses in Baldha's Rose Garden.

Hrishikesh Das, the zamindar of Dhaka, built a splendid 'Rose Garden' by collecting varieties of roses from home and abroad. The smell of roses had inspired the poet Shamsur Rahman. In the poem 'Ei Matowala Rait,' he describes the sentiments of a disorderly person:

'I am alive now

The scent of roses still comes to my nose.'

Fragrances were also produced from flower extracts in Dhaka. A lane was named 'Gandhi Goli' in homage to a perfume maker popularly known as Gandhi. Notable for having invented a refining method, he had an assortment of perfumes, including Champak, Arabian Jasmine and Jasmine.His products had gained popularity in the local market. He would also manufacture rose perfume and rose water. Nazir Hossain described the techniques of Gandhi in his book 'Kingbodontir Dhaka'.

In course of time, commercial floriculture became popular in Bengal and flower trade grew in volume. Today, Bangladesh can boast of a strong flower industry.

Hossain Muhammed Zaki is a Researcher. He can be contacted at [email protected]

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments