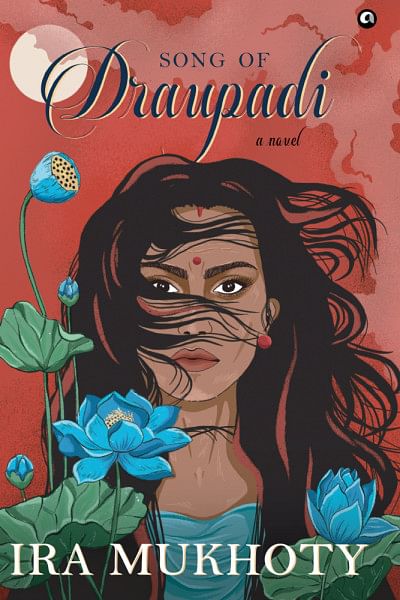

Ira Mukhoty's ‘Song of Draupadi’: An inside story of the Mahābhārata heroines

Ira Mukhoty, as a writer, is interested in the evolution of mythology and history, the erasure of women from these histories, and the relevance it has on the status of women in India. The Mahābhārata is famous for its historical battle and powerful men. But somewhere along the way, the stories of the great women of this tale were lost. As with her past books, Heroines: Powerful Indian Women of Myth and History (Aleph, 2017) and Daughters of the Sun: Empresses, Queens and Begums of the Mughal Empire (Brilliance Audio, 2018), Mukhoty aspires to recover those lost stories—this time through fiction—in her latest novel, Song of Draupadi: A Novel (Aleph Book Company, 2021).

The battle of Mahābhārata was a righteous war to claim the throne of Hastinapur between two groups of first cousins, the Kauravas and the Pandavas. The visual family tree at the beginning of the novel, elaborately illustrated, helped me understand these complex relations. But unlike in the tale of Mahābhārata, Song of Draupadi neither begins nor ends with the brothers' stories. A circular narrative encompasses the entire life of Draupadi, the protagonist of the story, from birth to death. As the novel progressed, I also encountered other influential women like Ganga, Satyavati, Amba, Gandhari, and Kunti.

My favourite character, Rani Satyavati of Hastinapur, hadn't come from a royal bloodline. Despite her background, the fisherwoman became the wife, mother, and grandmother of kings. Satyavati's pragmatic craftiness (she influenced the old, lustful Raja Shantanu to marry her and forced him to vow that only Satyavati's sons will be the rightful heir of Hastinapur) made her the most ambitious regent—more powerful than any king or male regent of that throne. Each of the women mentioned in the novel have thus played crucial roles in shaping the destiny of ancient India's Kshatriya rulership.

Mukhoty's lush poetic language recreated a palpable ambience of ancient India. She borrowed words like godhuli, takht, swayamvar, and brahmacharya from Hindi to retain the fragrance of 'Bharat'. Yet it was the tempestuous personality of Draupadi that startled me the most—a dark feral beauty born out of agni, with eyes like the blue lotus—vocal, fiery, and deadset on her vow. Draupadi, the Pandavas' wife, was wagered and lost by her husbands in a game of dice to the Kauravas. After the Pandavas lost her, one of the Kauravas forcefully dragged her by her hair and presented her as their slave in a courtroom full of men. All the elderly men of the family were present, yet nobody came to her aid. Bursting with anger and pain, Draupadi took an oath to avenge her humiliation: she would purify her hair with the blood of her culprit. Unafraid to criticise her husbands for their silence, she later incited them to war. As her character unravelled, I realised, Draupadi was not a devi to be put on a pedestal, she was a trailblazer.

Mahābhārata is a foundational story, particularly for the people of undivided India. Its verses were originally written by Brahmin men. This epic of valorous heroes, which was versified by society's upper-class male figures, pushed all the heroines behind the scenes. Their voices were muffled; everything the women said became ventriloquism. Mukhoty lets us hear those voices. Her heroes are flawed, gelded by lust and power and her heroines, clever and determined.

Among many age-old epics, the Ancient Greek epics Iliad and Odyssey are eminently popular. Their translated versions have been part of English Literature for many decades. Recently, we've also had the feminist retelling of these myths: Madelline Miller's Circe (2018) and The Song of Achilles (2011) are brilliant examples. Since the Sanskrit epic Mahābhārata is not as widely read in English as the Western epics Iliad and Odyssey, a lot of readers might be unfamiliar with the culture that the Mahābhārata represents. Song of Draupadi changes that.

Some terms, borrowed directly from Hindi or Sanskrit, might seem foreign to readers unfamiliar with the language. This is the only obstruction readers might face while enjoying this book. Another fact to be kept in mind: this is a work of fiction, not history. One must read the novel with an unprejudiced mind.

Maliha Huq is an engineer who loves reading books and (sometimes) enjoys writing essays. You can reach her at [email protected].

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments