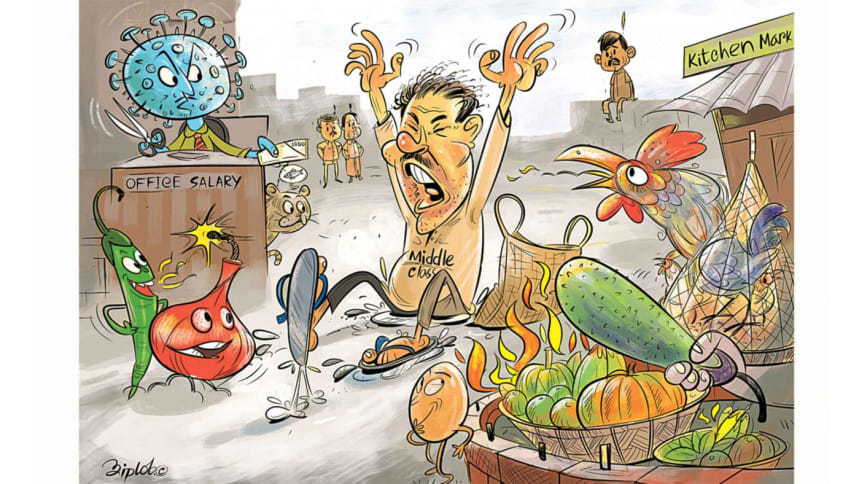

‘Price Controls! Can’t we do anything else to beat inflation?’

Antonio Guterres, the UN secretary general warned on May 18th that in the next few months we shall be facing the "spectre of a global food shortage" which could last for years. According to the Economist magazine, the high cost of staple foods has already raised the number of people who face acute food insecurity by 440 million to 1.6 billion globally. As a consequence, "Political unrest will spread, children will be stunted, and people will starve."

What does a government do to alleviate the pain and suffering caused by rising prices and shortages? In 1539, faced with a similar prospect and a cold winter, King Henry VIII of England advised Cromwell, his aide, "They [the citizens] fear the winter, poor devils. Reassure them that should there be scarcities, no one will profit from their distress. Proclaim a fixed price for grain if you must. Set up a commission to investigate hoarding" (Hilary Mantel, The Mirror and the Light). Interestingly enough, food scarcity, profiteering, hoarding and fixed price for food grains are themes that are relevant even today, even after almost five centuries since then.

With inflation raging out of control across the globe and no end in sight, there is a temptation to talk about price control or mandatory price ceilings. Unfortunately, price control by the government has not worked very well in the past and also has acquired a bad reputation in political and economic circles. However, with the inflation rate now almost in the double digits and the price of essential items soaring every day, the public and many other quarters are seeking alternatives to bring down the price level, or at least, to bring it under control. So, what can be done and what is the alternative to price control? Is there anything else available besides raising interest rates, growing more food and importing soybean oil, or using other measures that take a little time to kick in? Central banks and the economists who guide them are aware that there are no silver bullets to kill inflation. But there is a range of policy tools open to the government.

Many forecasters have said that the current round of inflation is "transitory" and once the supply chain bottlenecks are removed and China starts to make more consumer goods, things will go back to normal. But that was more than a year ago! There's nothing that hits the pocketbook of the average citizen harder than the rising prices of essentials. Furthermore, there is no question that inflation is bad for the future of the economy and the political future of a government party. Just as a threat from a foreign enemy or domestic entity never fails to get a ruling party to marshal its resources and respond with all its might to combat these evil forces, runaway inflation calls for action from the authorities.

Bangladesh government has taken up arms and tried to blunt the impact of rising prices with an increased supply of essential commodities, greater subsidies, and exchange rate regulations. But to no avail. Swinging into action, the Directorate of National Consumers Right Protection (DNCRP) last week fined 64 traders Tk 9.18 lakh across the country for their failure to protect consumers' rights. The news media reported that the directorate imposed the fines during market monitoring activities in 33 districts of the country, including Dhaka. All this is price control in practice.

Price control, however, remains a touchy area. A government cannot really regulate the price of goods in the market and any effort to exercise "command and control" tools to keep the price of gas at the pump, rent for the middle and lower-middle-income classes, and everyday consumer prices (for food grains, edible oils, sugar, meats, and lentils) may eventually come back to haunt the country sooner or later.

Nonetheless, the government has to exercise its authority to keep an eye on essential items, strengthen its monitoring cells, provide subsidised staples for the lower-income consumers, and use "moral suasion" to keep traders in line. Price control is bad but the government has many other tools at its disposal to bring about price stability.

Moral suasion seeks to persuade, rather than force, an entity to act in a certain way through rhetorical appeals, persuasion or implicit threats. In economics, moral suasion is more specifically defined as "the attempt to coerce private economic activity via governmental exhortation in directions not already defined or dictated by existing statute law," (JT Romans, "Moral Suasion as an Instrument of Economic Policy", The American Economic Review).

The only country which has had any measure of luck with price control over the long haul is China. The inflation rate in China was 2.39 percent in 2020, 2.9 percent in 2019; 2.11 percent in 2018; and 1.56 percent in 2017. The CPI forecast for 2022 and 2023 are 2.2 and 2.3 percent, respectively. Obviously, China has tight "state-dominated controls on its economy, which enables it to manage inflation differently compared to other countries. In China, changes are made to subsidies and other price control measures to check inflation."

How do you control inflation in a market economy? There is no easy answer to this vital question. Today, every politician and average citizen is asking and looking for an easy fix for inflation. How do you bring down the price of soybean oil? Well, to allow more imports would be an easy answer. What about the price of food? Well, you cannot ask for an immediate increase in the supply of grains, meat, edible oil, sugar, or lentils. Because, as we all know these solutions don't really solve the problem overnight, what with the war in Ukraine, a depreciating taka, and new supply chain bottlenecks. The goal for the government ought to be to manage the current crisis and overcome the immediate hurdles with a prudent mix of macroeconomic policy, lower tariffs on imports of everyday use, and regulatory guidance.

Unfortunately, there is no easy path to price stability in the current volatile environment. Market forces are at the helm. Some prices go through ups and downs, and others only keep going up. Take the case of gasoline or crude oil.

When supply is abundant, the price goes down. On the other hand, as we have seen over the last 50 years, when there is war in the Middle East or the oil-producing countries suffer any domestic turbulence, the oil market is on fire. Fortunately, these are expected to be temporary, and things calm down. On the other hand, prices of electronic items have gone down in real terms. For Bangladesh, prices of many imported items have recently seen upward pressure due to global shortages, devaluation of the taka, and some degree of market influence by traders or syndicates.

The warnings of Guterres and the Economist Intelligence Unit cited at the beginning only reinforce the hands of policymakers seeking directions or avenues for market intervention. In a recent ruling, the High Court of Bangladesh advised the government to take measures to rein in the syndicates which manipulate the prices of staples.

Dr Abdullah Shibli is an economist and works for Change Healthcare, Inc., an information technology company. He also serves as Senior Research Fellow at the US-based International Sustainable Development Institute (ISDI).

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments