Right to information in the age of authoritarianism

As authoritarianism creeps in across the world, the ideals of participatory democracy and representative governance have taken a back seat once again in many countries. Since the end of World War II more than seven decades ago, the scope for people's participation in the affairs of the state has waxed and waned, in countries old and new – and now it seems to be receding again.

The incredible devastation and human suffering caused by the war sparked the quick generation of international principles, norms and standards, in which people were put at the centre of all visions for a new world. International legal instruments sprang up, in which the rights and welfare of the people were the main focus. Soon these were relayed into national laws.

An important outcome of this development was the rejection of the traditional concept of governance by political elites in favour of the concept of people's sovereignty over all affairs of the state. The idea of "active citizenship" in matters of governance began to evolve. Though derailed frequently during the Cold War period, it got back on track firmly after the demise of the Soviet Union and the emergence of new democracies.

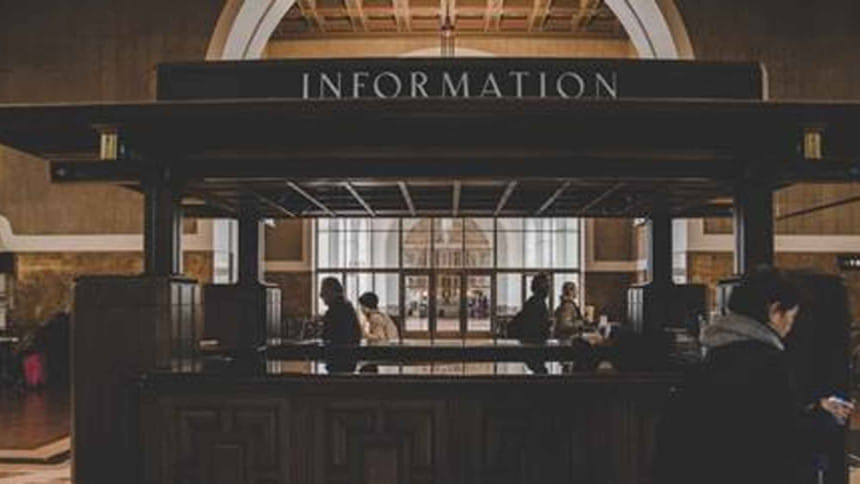

It was during this period that the concept of active citizenship took a big leap forward. New democracies joined their older counterparts to adopt freedom of information (FOI) act or right to information (RTI) act. These laws sought to end the culture of secrecy in government work and to empower citizens with a legal right to seek relevant information from public authorities to monitor their work. They were seen as "auxiliary precautions" against government proclivity to keep citizens in the dark about their activities.

But adopting a law and putting it to actual practice are two different things. So as the number of countries with FOI/RTI laws grew, scholars and activists were drawn to measuring the effectiveness of these measures. Their findings reveal a rather discomforting picture of many governments adopting the law as "window dressing" to improve their international image or paying the law a mere lip service because of domestic or international pressures. Hence, governments do little to implement the law proactively. Meanwhile citizens are generally uninformed about their responsibilities to make effective use of the law.

An important finding of the scholars indicates that the success of RTI law depends largely on society's view of citizenship and the government's commitment to that view. The most prevalent understanding of citizenship in many democracies limits the role of citizens to obey the laws, passively participate in periodic elections and let elected representatives deal with the matters of governance. People feel far removed from the workings of the government. In such cases, the task of preparing citizens to assume a more participatory role in the matters of governance, fostering closer interaction with government bodies, requires an active movement. And it is for the citizens to do that. FOI/RTI laws provide them with the tools. Movements like this have sprung in many countries, including in our neighbour country India.

To begin with, users of the law must understand that governments have a legitimate need to keep a variety of information hidden from the general public. FOI/RTI laws have clearly identified the areas which call for safeguards, including those related to sovereignty, public security or individual privacy. The problem arises when public officials use the exemptions mindlessly, as a matter of habit, or to cover their own mistakes or wrongdoings. Unless this is checked, the law is doomed.

This is where the concept of active citizenship comes in. Citizens should learn what types of information will help them discover if government offices are doing their jobs properly. Secondly, while it is easier to use the law for personal reasons – to ask for information relating to the release of pension payments – the real value is in establishing government accountability, i.e. to ask for information relating to public expenditures. Such use requires better understanding of the scope and extent of the exemption clauses. Unless that happens, officials will continue to use exemptions to deny disclosure.

To deal with such abuse, citizens normally depend upon the arbitration role of an independent and impartial information commission. But where that is not the case, the watchdog role of citizen groups becomes important. In Bangladesh, a large number of RTI applications are rejected regularly on the basis of exemption clauses. It is time our civil society turned its attention to the problem and helped establish a mechanism, whereby such arbitrary decisions are put under scrutiny and dealt with legally.

Our judiciary has helped in the past. But the practice of seeking the opinion of the High Court is still very limited. Since decisions of the Information Commission are final, the only way of ensuring proper application of the law is to seek the court's guidance. There is a clear need to develop proper jurisprudence in this area, as has been the case in many older democracies.

Time has come for our social and political elites to match their passion for fair elections in the country with a similar zeal to promote proper application of the RTI Act as an instrument to establish transparency and accountability in governance. This is one law which, when properly used, can yield beneficial results even in difficult political times.

Dr Shamsul Bari and Ruhi Naz are chairman and assistant director (RTI), respectively, at Research Initiatives, Bangladesh (RIB).

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments