Plassey: Myths and reality

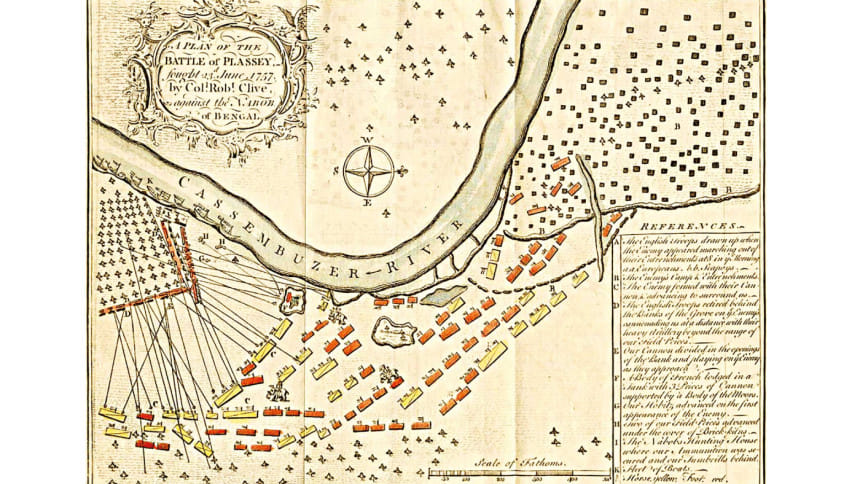

Each year on 23 June arrives an occasion of template lament for Bengalis: the defeat of Siraj-ud-daulah at Plassey at the hands of forces led by Robert Clive—and Bengal's subsequent quick subjugation by the East India Company. Indeed, the quick subjugation of the Indian Subcontinent by both Company and Crown in a blistering 190-year sprint from that Monsoon day in 1757 until a muggy August in 1947. The fact that this article is being written in English and not French, Marathi, the language of the Bōrgi, or—a long historical shot—Persian, is an indication of the dexterity with which 'John Company' and the British government navigated and dominated South Asia's shape-shifting dynamics.

This rubric included Britain's arch-enemy France (along with initially robust competition in Bengal from the Dutch). The back story of Plassey—the battle as well as the run-up to it—is a mix of aggressive mercantilism married to geopolitics, an often-diminished fact. Few works acknowledge just how much the French were a factor in the run up to Plassey. Then there was the Maratha confederacy that ran riot from western India all the way to the opposite bank of the Bhagirathi in Murshidabad. And there was the crumbling pay-per-farman Mughal Empire.

Plassey—Polashi—was never a binary conflict. Black and white. Sacrifice and betrayal. Horrid English and disadvantaged natives. The descriptions of a hapless Siraj, and a crafty Clive backed by a treacherous Mir Jafar are not absolute. This seminal event in Bengal and South Asian history is a Rashomon truth, as it were. That it continues to be portrayed in binary terms even by some eminent historians and intellectuals, let alone by pamphleteers who live off emotional history for political gain, is outright misdirection—and Plassey's true lament. Let me illustrate this with just a few of numerous examples.

Take the myth that John Company were content in Bengal until the arrival of Siraj to the masnad in April 1756, upon his grandfather Alivardi's death. This myth discredits the contentious relations the nawabs of Bengal had with the British East Indian Company in Bengal from the time of Shaista Khan's governorship in the late 17th century. Indeed, Job Charnock, who later helped establish the Company presidency in Calcutta 1690, was kicked out of the Company trading depot in Cossimbazar—Qasimbajar—alongside a near-total shutdown of trade, by Shaista, on account of aggressive manoeuvring. Charnock was merely following in the haloed military-mercantilism steps of Thomas Roe, who arrived as ambassador of the court of King James I to the court of Emperor Jahangir in the early 17th century. Roe and his colleagues diligently carried out the Company S.O.P.: Treat with the Mughals, threaten them, and blockade Mughal shipping in the Arabian Sea and Bay of Bengal if need be. Play hardball.

The Company and Charnock returned to conduct business in Bengal only after Shaista was recalled by Emperor Aurangzeb. This happened nearly 70 years before Siraj became nawab. Subsequent governor-nawabs, including Murshid Quli Khan, and later, Alivardi, who defeated Sarfaraz Khan to rule Bengal, had numerous run-ins with the Company over trade, duties, concessions, breach of protocol, overstepping command-and-control boundaries and, occasionally, military overreach. The British repeatedly attempted to paper these over with abject apologies and 'gifts'.

As late as 1749—seven years before Alivardi's death and Siraj's accession—Company records speak of attempts to mollify Alivardi with the gift of a "fine Arab horse" as the nawab had squeezed trade to and from Calcutta and Dhaka as one of the outcomes of a dispute the British had with local Armenian traders.

Alivardi wasn't mollified. He soon began to stop the boats of British merchants, and cut off the supply of provisions to the British factory in Dhaka. Alivardi's troops surrounded the factory at Qasimbajar, reminiscent of the time of the nawab Shaista, and not unlike what Siraj would do in a few short years. The Company capitulated by paying off Alivardi through the Jagat Seths, bankers who would shortly conspire against Siraj—but they had actually been conspiring against Siraj before he became nawab.

The Company's Consultations of 31 August 1749 note: "The English trade being stopped and the factory at Cossimbazar surrounded with troops by the Nawab owing to the dispute with the Armenians the English try through the Seets to propitiate him, but his two favorities demand a large sum of money Rs. 30,000 for themselves and 4 lakhs for the Nawab, at last after much negotiation the Armenians expressing themselves satisfied the Nawab becomes reconciled, but the English got off after paying to the Nawab through the Seets …"

Various disputes continued right until 1755, a year shy of Alivardi's death, a matter of routine give-and-take and written off by the Company as both an investment in goodwill and the cost of doing business.

The Company reached out to Siraj too—a gesture that was reciprocated. This happened in 1752, when Alivardi declared Siraj as his heir and successor. Siraj visited Hugli, the trading town north of Kolkata on the western bank of the eponymous river. Company representatives travelled upriver to meet the crown prince, and Company records note they were received by Siraj with "… the utmost politeness and distinction far superior than was paid the Dutch or French …"

They took gifts for Siraj. A chronicler, the Reverend James Long quoted Company ledgers to observe:

"In the accounts of presents to Suraja Doula and his officers on their visit to Hugly are entered 35 gold mohurs, = Rs. 677; ready money Rs. 5,500; wax candles Rs. 1,100; a clock Rs. 880; looking glasses 2 pairs Rs. 550; 2 marble slabs Rs. 220; pistols 1 pair Rs. 110; a diamond ring Rs. 1,436; to Alliverde's wife and women 26 gold mohurs,= Rs. 429; fukiers Rs. 184 … the sum total in ready money amounted to Rs. 15,560. In return the president of the council in Calcutta received a robe of honour and an elephant."

This honour to his favourite grandson greatly pleased Alivardi. It pleased Siraj too. He would write to Roger Drake, Company chief in Calcutta, adding his pleasure to a pro-Company parwana: "…you are a great man, and that greatness becomes you, the head of all merchants, and the standard of merchants."

Siraj was then a friend as much as any nawab, established or on the make, could be a friend, strategically fêted and suitably befriended. The teenage heir apparent hadn't yet been magically transformed into the demon the British—and their post-Plassey allies, who contributed to creating a history of victors—loved to hate, the man whose forces would pressure Drake and most of his colleagues to abandon Calcutta less than four years later.

(Maybe Siraj-ud-daula was unpredictable, perhaps a mystery. Even when he became relatively better known to the Company, the political nuances and personalities of Bengal evidently remained as arcana to the board of directors in London. As the writer and historian Piers Brendon wryly observes, '…one Company director did ask if Sir Roger Dowler was really a baronet.')

Here are some other often-ignored aspects of Plassey. The conspiracy against Siraj in Murshidabad predated Plassey and Clive's arrival in Bengal over the winter of 1756-57. Mir Jafar, who was sacked by Siraj as paymaster general of the Bengal army had, with the help of Ghaseti Begum, Siraj's aunt, conspired to incite Shaukat Jang, the nawab of Purnea and Siraj's cousin, to march on Murshidabad. Shaukat Jung did, twice—once abortively and the second time fatally, for him. Ghaseti Begum had it in for Siraj even before Siraj was made heir apparent by her father. She wished for Siraj's younger brother Ikram-ud-daulah, whom she had adopted, to succeed Alivardi. Her hate for Siraj grew after Ikram died of illness and Siraj was elevated to heir. When the Plassey conspiracy was finally sealed as late as April-May 1757, just weeks before the battle, Clive essentially walked into a ready environment and leveraged it with the backroom help of the Jagat Seths, who read the political and economic tea leaves and threw their lot in with the British over the French and Siraj.

Moreover, the British were determined to rid the French from Bengal—the trading plum for both European companies and their countries—even before Clive arrived in Bengal. He arrived not to wrest Bengal from Siraj, but basically in the hope of negotiating with Siraj to win back the Company's possessions and concessions in Bengal the Company had lost in 1756 through the policy and military overreach of the Calcutta Council. Clive & Co. were focused on the French, their rivals in Europe, the Americas, Africa and Asia, as much as regaining trade in Bengal.

"I hope we shall be able to dispossess the French of Chandernagore …" Clive had written in a letter to the Company's Select Committee in Madras on 11 October 1756, five days before the Company & Crown fleet sailed from Madras to Calcutta. The imperative to win the French bastion in Bengal was underscored in a letter dated 13 November by the Select Committee in Madras to Admiral Charles Watson, a Royal Navy officer who commanded the naval arm of the expeditionary force; Clive commanded the infantry: "If you judge the taking of Chandernagore practicable without much loss it would certainly be a step of great utility to the Company's affairs and take off great measure the bad effects of the loss of Calcutta by putting the French in a position equally disadvantageous."

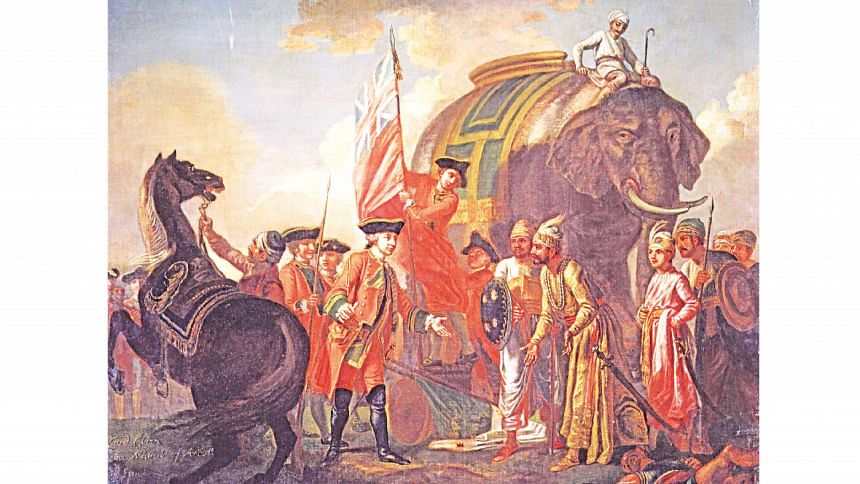

And what of the so-called Lion of Bengal, later celebrated as "Clive of Bengal," and gilded into British peerage as Baron Plassey? That pushy, often-brilliant, opinionated but nervous wreck of an opium addict who nearly drowned on his way to take up his position as a lowly Company Writer in Madras? That "heaven sent general" who, despite signing the Plassey conspiracy with Mir Jafar that guaranteed Clive & Co. great riches and that disgruntled noble the masnad of Bengal, was far from sure of victory even hours before the battle? The desperate man who was ready to make peace with Siraj as if nothing had passed between them?

A whiny, insecure, desperate Clive who had staked his career and the Company's fortunes on a thrown of campaign-dice, wrote to Mir Jafar on 22 June, the day before the battle:

"I am determined to risque everything on your account, though you will not exert yourself … If you will join me at Placis, I will march half way to meet you, then the whole Nabob's army will know I fight for you. Give me [leave] to call your mind how much your own glory and safety depends upon. Be assured if you do this you will be the Subah of these Provinces, but if you cannot do even this length to assist us I call upon God to witness the fault is not mine, and I must desire you your consent for concluding a Peace with the Nabob, and what has passed between us will never be known ..."

There was no guarantee even hours before the battle commenced at 8 a.m. on 23 June 1757. Indeed, I would maintain that it wasn't so much that Monsoon showers spoiled Siraj's party by wetting his army's gunpowder—in addition to most of his army standing idle in conspiracy to see which way the storm winds travelled—but Siraj's own insecurity in leadership.

There are numerous examples of non-binary truths about Plassey. But there's a stodginess about visiting the information-soaked by-lanes of Plassey, those exciting neighbourhoods beyond the ghettoes of template interpretations. Colonial pursuits and the other side of that coin, lamenting Siraj and Bengal's abject fate, have formed the bedrock of such historiography. Binary history is an expired commodity. Certainly Plassey deserves better.

Sudeep Chakravarti is an historian, author, columnist, and visiting professor of South Asian Studies at ULAB, Dhaka. He has written several books including Plassey: The Battle that Changed the Course of Indian History (Aleph, 2020).

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments