Rohingya genocide case to proceed

The World Court yesterday rejected Myanmar's objections to a genocide case over its treatment of the Muslim Rohingya minority, paving the way for the case to be heard in full.

Myanmar, now ruled by a military junta that seized power in 2021, had argued that Gambia, which brought the suit, had no standing to do so at the top UN court, formally known as the International Court of Justice (ICJ).

But presiding Judge Joan Donoghue said the 13 judge panel found that all members of the 1948 Genocide Convention can and are obliged to act to prevent genocide, and the court has jurisdiction in the case.

"Gambia, as a state party to the Genocide convention, has standing," she said, reading a summary of the ruling. The court will now proceed to hearing the merits of the case, a process that will take years.

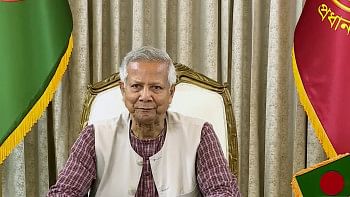

Bangladesh has welcomed the judgment.

"Bangladesh maintains that the question of international justice and accountability will be critical in finding a durable solution to the Rohingya crisis, and would also prove to be a confidence building measure for the sustainable repatriation of the Rohingyas to their homes in Myanmar with their legitimate rights restored," the Ministry of Foreign Affairs in Dhaka said in a statement.

Gambia, which took up the cause after its then-attorney general visited a refugee camp in Bangladesh, argues that all countries have a duty to uphold the 1948 Genocide Convention. It is backed by the 57-nation Organisation for Islamic Cooperation in a suit aiming to hold Myanmar accountable and prevent further bloodshed.

A separate UN fact-finding mission concluded that a 2017 military campaign by Myanmar that drove 730,000 Rohingyas into neighbouring Bangladesh had included "genocidal acts".

While the court's decisions are binding and countries generally follow them, it has no way of enforcing them.

In a 2020 provisional decision it ordered Myanmar to protect the Rohingya from genocide, a legal victory that established their right under international law as a protected minority.

However, Rohingya groups and rights activists say there has been no meaningful attempt to end their systemic persecution and what Amnesty International has called a system of apartheid.

Rohingyas are still denied citizenship and freedom of movement in Myanmar. Tens of thousands have now been confined to squalid displacement camps for a decade, reports Reuters.

The junta has imprisoned democratic leader Aung San Suu Kyi, who defended Myanmar personally in 2019 hearings in The Hague.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments