1971 and the case for secularism in Bangladesh and India

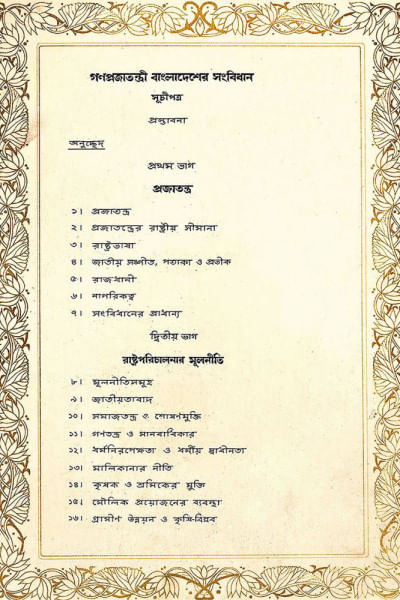

Bangladesh has just celebrated fifty years of independence; this year also marks fifty years since its Ganoparishad ratified the Constitution of Bangladesh. Anniversaries are as worthy occasions as any to recall why certain ideological principles were chosen to guide the new nation.

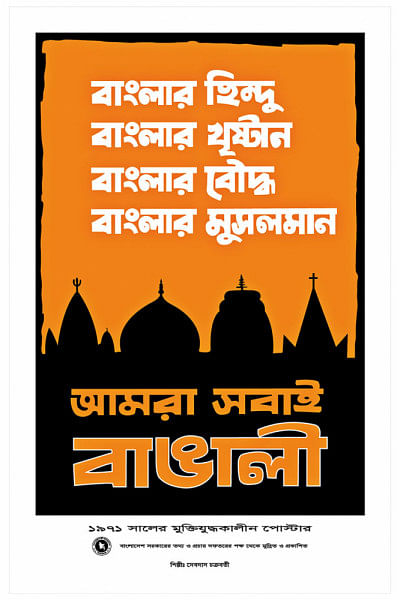

On the adoption of dharma-nirappekhata (translated as secularism) for instance, Kamal Hossain, the first law minister of Bangladesh, clarified to me in an interview in 2018 that this principle gained salience during the war of 1971. It was then prime minister-in-exile Tajuddin Ahmad who developed the doctrine as a response to Pakistan's onslaught on East Pakistan in the name of Islam. In an 18-point missive announced in May 1971, Tajuddin Ahmad advised his compatriots to be united as Bengalis, and not divide on lines of religion, party, or class ["Dharma, dal, o sreni nirbisheshe, jonogon Bangali hishebe oikkoboddho"]. Under his instructions, Bangladesh Betar also routinely broadcast recitations from the Quran, Gita, Tripitaka and Bible, an echo of Gandhi's practice of multi-faith prayer meetings.

To counter Pakistani propaganda that the war was being fought to keep an Islamic nation united, Tajuddin Ahmad exhorted the Arab world to support the cause of Bangladesh. "… that Yahya Khan's soldiers are fighting for Islam's rights … this idea is an unfortunate distraction, [a lie]. He is using Islam to go against the wishes of the public and to stop people's exercise of human rights." Much the same was emphasized by Bangladeshi leader Maulana Bhashani in a series of letters to world leaders including Anwar Sadat of Egypt and Abdel Khalek Hassouna of the Arab League "… all these unspeakable acts have been perpetrated by a Muslim army on an overwhelmingly Muslim population."

The service chiefs of Pakistan, together with none other than General Tikka Khan, stood at attention and saluted the flag of Bangladesh. The symbolism and significance of this act, and of the occasion, could not escape anyone present.

However, the resistance to the misuse of Islam to paper over differences between both wings of Pakistan was not restricted to the time of the war. In the Constituent Assembly debates that preceded the adoption of the first constitution of Pakistan in 1956, Sheikh Mujibur Rahman, who had already served time in Pakistani prisons, argued that the principle of detention without trial was un-Islamic. He reminded the Assembly of the provisions of the Quran and Sunna: "Nobody can be punished without trial. Even Allah will not punish anybody without trial. If I committed a sin, I will be sent to hell—after proper trial. If I have done good, I shall be sent to heaven—after trial. Let us see what this 'Islamic Constitution' provides: anybody can be detained without trial 'in the interest of public order and Pakistan.'" Mujib also scoffed at the forms that were being supplied by Karachi University to students to pledge that they would not indulge in activities "subversive to Pakistan or prejudicial to the University of Karachi." What right had the state to assume that the students were opposed to the state? Mujib as well as H. S. Suhrawardy also emphatically protested Islamic provisions such as naming the nation the "Islamic republic" of Pakistan and reserving the post of head of state to a Muslim.

Even so, fourteen years later, when chief martial law administrator General Yahya Khan announced that one of the five fundamental principles of the Legal Framework Order (LFO) under which elections were to be held would be adherence to "Islamic ideology, which is the basis for the creation of Pakistan", the Awami League accepted the principle. It was war-time atrocities in the name of Islam that turned the tide towards dharma-nirappekhata or secularism. Yet what did secularism mean to Bangladesh's founders?

Shortly after the war, Tajuddin Ahmad met with a Buddhist delegation. According to a report in the Bangladesh Observer, the prime minister declared that Bangladesh would be a "completely secular state which would ensure absolute freedom to every religion. He said that the state would never interfere in any religion but at the same time he said it would not allow anybody to exploit the people in the name of religion." Such an understanding of secularism as meaning the "absence of - communalism in all its forms; the granting by the state of political status in favour of any religion; the abuse of religion for political purposes; any discrimination against, or persecution of, persons practicing a particular religion" was enshrined in article 8 of the Constitution of Bangladesh. In marked contrast to the 1956 (and 1973) Constitutions of Pakistan, the 1972 Constitution of Bangladesh did not reserve the post of head of state to a Muslim.

Critically, the new prime minister Sheikh Mujibur Rahman spoke firmly against weaponizing religion. In his last speech before the Constitution Bill was passed on November 4, 1972, he underlined that secularism did not mean being opposed to the practice of religion. His only difficulty was with the misuse of religion as a political weapon as had happened over the last 25 years. His words are worth reading in full:

Dharma nirappekhata mane dharma hinata noy. Musolmanra tader dharma palon korbe- tader badha deuar khomota ei rashtre karo nai. Hindu tader dharma palon korbe-tader badha deuar khomota ei rashtre karo nai. Bouddhora tader dharma palan korbe-tader keu badha dan korte parbe na. Chrishtanra tader dharma palon korbe-keu badha dite parbe na. Amader shudhu apotti holo ei je, dharma ke keu rajnoitik ostro hishabe bebohar korte parbe na.

25 bochor amra dekhechi, dharmer nam e juachuri, dharmer nam e shoshon, dharmer nam e beimani, dharmar nam e ottachar, dharmer nam e khun, dharmer nam e baebhichar- ei Bangladesh er matite e shob choleche. Dharma oti pobitro jinish. Pobitro dharmake rajnoitik hatiar hishabe bebohar kora cholbe na.

"Our secularism is not against religion. Muslims can practice their religion—the state has no power to stop them. Hindus can practice their religion—no one has the power to stop them. Buddhists can practice their religion—no one has the power to stop them. Christians will practice their religion—no one can stop that. Our only reservation is about using religion as a political weapon.

"We have seen in 25 years, we have seen theft in the name of religion, misrule in the name of religion, betrayal in the name of religion, torture under the name of religion, murder in religion's name and injustice under the name of religion—all has taken place in Bangladesh's soil. Religion is a holy thing. Using religion as a political weapon will happen no more."

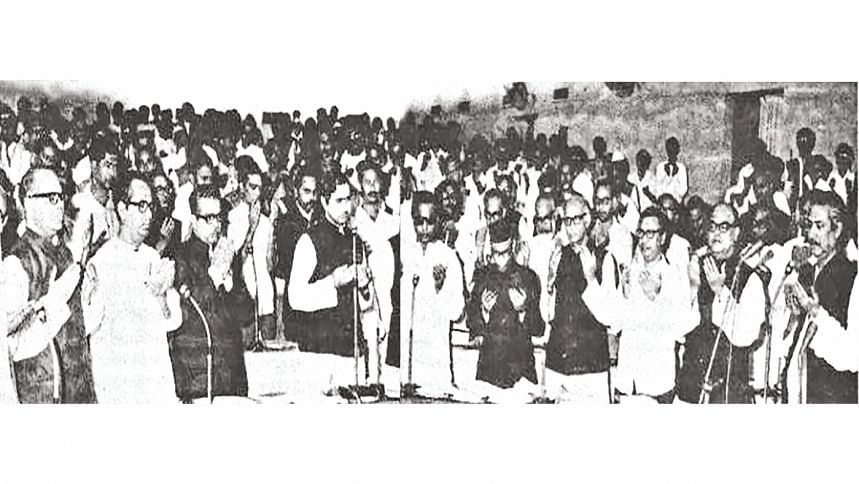

Mujib was not alone in his understanding of secularism as embodying respect for religion. Minutes after this speech, we have photographic evidence of the entire Assembly raising their hands for prayer as Maulana Tarkabagish recited from the Quran.

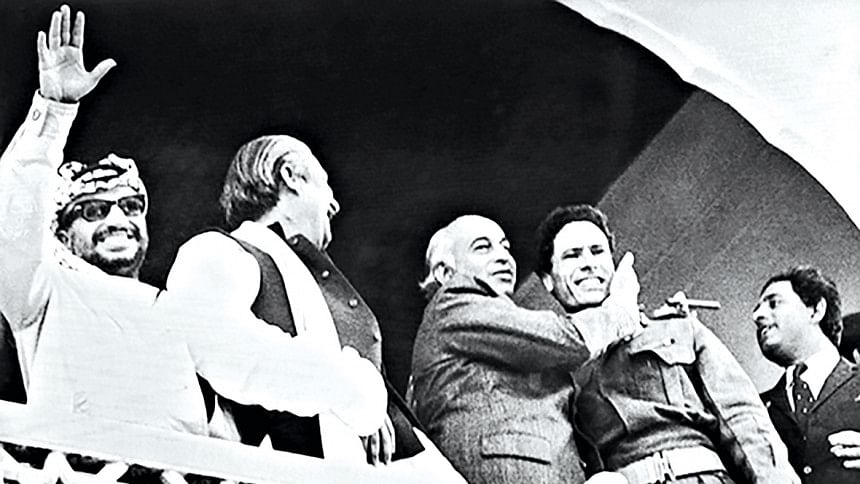

The idea that Bangladeshi secularism was not opposed to the practice of religion had to be repeatedly explained to Muslim leaders abroad, who were reluctant to recognize Bangladesh as sovereign and independent. In his memoirs, Kamal Hossain recalls the negotiations that finally resulted in Bangladesh being accorded formal recognition by Pakistan so that its delegates could attend the formal opening ceremony of the Islamic Summit in Lahore. Hossain remembered listening to the Bangladesh national anthem, in Pakistan:

Our arrival in Lahore was, undoubtedly, a historic moment, charged with emotion. The flag of Bangladesh had been hoisted and, when the guard of honour was presented, the military band started to play Amar Sonar Bangla (Bangladesh's national anthem). Since the shortened version which had been adapted for the national anthem was not available in Pakistan, the band played the national anthem for nearly 20 minutes! The service chiefs of Pakistan, together with none other than General Tikka Khan, stood at attention and saluted the flag of Bangladesh. The symbolism and significance of this act, and of the occasion, could not escape anyone present.

Amar Sonar Bangla was composed by Rabindranath Tagore, whose songs had only recently been taken off Radio Pakistan for being anti-Islamic. The ironies of the moment were abundant. Hossain has also detailed his meeting with King Feisal of Saudi Arabia at some length:

When King Faisal, as anticipated raised the question about secularism, I took the opportunity to explain the background in which the provisions had been made in the Constitution. … Pakistan, while describing itself as an Islamic state, had been responsible for actions over the years and in particular in 1971, that had brought Islam into disrepute and had destroyed the country. There should be no mistake that the Muslims of Bangladesh were no less devout than those of Pakistan: but, having experienced the hypocrisy and intolerance that resulted from the abuse of religion for political purposes, Bangladesh had decided to make provisions in its Constitution which would promote an environment free from religious intolerance. It was in keeping with the finest traditions of the Prophet of Islam (PBUH) to seek to create conditions in which religious minorities would feel secure, and citizens would not oppress each other in the name of religion. Bangladesh, with a Muslim majority, had a tradition of communal harmony and religious tolerance, in which other communities could also live in peace.

Sheikh Mujib spoke similarly to Muammar Gaddafi at the Non-Aligned Summit in Algiers in 1973. He reiterated Bangladesh's commitment to all its people, Muslim and non-Muslim:

Our secularism is not against religion. Our secularism stands for harmony among members of all religions. Indeed, in the opening of the Koran, Allah is described as Rabbul Alameen, the Lord of all creation and not of Rabbul-Muslimin, the Lord only of Muslims. This is the spirit which underlines our secularism.

Across the border in India

Under Tajuddin's instructions, Bangladesh Betar also routinely broadcast recitations from the Quran, Gita, Tripitaka and Bible, an echo of Gandhi's practice of multi-faith prayer meetings.

Just as the trajectory of the war transformed Bangladesh's understanding of the extent to which religion could be misused, a similar shift happened in neighboring India. Member after member of the Congress party rose in India's parliament to proclaim that only the power of Indian secularism could have defeated Pakistan's divisive "two-nation" theory; the divisive rhetoric of the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh and the Jana Sangh could not have defeated Pakistan. N. K. P. Salve of Nagpur revealed his local knowledge of the working of the RSS while interrogating "It is said that this institution is a cultural institution. But what sort of Indian culture is it that it is not open to Muhammedans, Christians? Is character building not necessary for a Christian's or a Muhammedan's son?"

Salve also distinguished between the approach of the Jana Sangh and the Congress: "It is said that Jana Sangh is happy at the victory and liberation of Bangladesh, and at India's contribution to the liberation of Bangladesh. Certainly, you are happy and we are happy except that your reasons are different and our reasons are different. For us it was a fight against the two-nation theory and for secular ideals which we hold dear. For you, we apprehend, it was a different fight. You wanted an Islamic nation to be destroyed. That has happened and you are happy." Salve spoke of feeling "sorry for the people of Pakistan. … What wrong have the people of Pakistan done to us? They have been victims of a very pernicious system." He noted that whereas the Congress had not wanted to continue the war after Bangladesh was liberated, the Jana Singh differed in its approach. "All these things take us to believe that your reasons for our victory in Bangladesh are entirely at variance – in fact, they are contradictory to the reasons, which we cherish, for the liberation of Bangladesh." Salve's sense of goodwill towards the people of Pakistan was shared by a cross-section of the ruling class.

In those confident, purposeful months following the war, and the general election of 1971 which had also given the Congress party an absolute majority, India's parliament passed amendments to sections of the Indian Penal Code which would strengthen its ability to fight communal and paramilitary organizations and make it a criminal offense to cast allegations on any community or group's allegiance to India. Four years later, during the Emergency, the parliament also amended the constitution to insert "secularism" into its preamble. Yet mere words could not staunch the progress of RSS shakhas that were slowly and firmly sowing deep roots across India.

Neeti Nair teaches history at the University of Virginia. She is the author of Changing Homelands: Hindu Politics and the Partition of India (Harvard University Press and Permanent Black, 2011). Her new book Hurt Sentiments: Secularism and Belonging in South Asia, is forthcoming from Harvard University Press in spring 2023.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments