What I write about when I write love stories

A long time ago, when I was a young writer who had just published his first collection of short stories and had just been married to a young and lovely woman, I wrote a love story in the first person, which created two unanticipated problems.

First, my wife stopped talking to me, and second, some of my friends who read the story accused me of humiliating the whole community of Bengali Muslims, being that the protagonist of the story, a Bangladeshi Muslim boy, fell in love with a Hindu girl from West Bengal, India, who disrespected his love.

Set at a university in Moscow during the final days of the Soviet Union, the story describes the complex relationship between the Bangladeshi boy from a middle-class Muslim background and the Indian girl from a Hindu upper caste and elite (Brahmin) family. This family had been forced to migrate to West Bengal as a result of the bloody communal Hindu-Muslim conflicts and the subsequent partition of India in 1947. Their forefathers were from the same area of East Bengal (now Bangladesh) but with very different religious, economic, and social statuses.

To my wife, the story was very plausible evidence of my "loose" character. To my friends, it was humiliating for Bengali Muslims because the Bangladeshi protagonist was portrayed as a coward and a defeated character, a product of the author's "imagined" inferiority complex.

I promised my wife that I would never again write love stories in the first person singular, and then broke that promise again and again: I kept writing. Once they were published, I never reflected on them or tried to analyse them further.

But just a few days ago, when I was told to talk at a panel discussion about writing (or not writing) about love, I started looking back at my stories with an analytical eye and discovered that they were stories not about love but some other emotions and behaviours; some basic, intuitive, organic, crude, raw, and straightforward, some cultivated, subtle and complex. The above story was a tale of romantic infatuation and hereditary/racial prejudices.

A few years after I wrote that story, I wrote a novel. The main protagonist was a powerful female character who had divorced her husband for the sake of her professional career (she was a diplomat). Then she fell in love (or so she claimed) with a journalist, a gentleman of quiet and meek personality, whose wife had abandoned him.

They marry, but soon after the wedding, the gentleman starts un-enjoying his wife's dominating behaviour, which he used to enjoy before they were married when he used to call her "my queen," without anticipating that this romantic queen might turn into a real tyrant.

However, the marriage does not break, primarily because the husband, a naturally meek and submissive person, realises that he should be more accommodating than his wife. She is naturally dominant and cannot help her nature. But his ego refuses to recognise his submissiveness as a defeat and comforts itself with this philosophy: jey shohe, shey rohey, meaning, those who endure, win.

So you see, this is not just a story about sincere or pretended love, but about a cold war between two intelligent, cultivated, modern human beings. Most of my short stories and novels about male-female relationships are like this. I did not write them this way; I don't enjoy writing about conflict or combat; they become like this naturally, as if following the natural laws of the worlds I create. And so I came to wonder why: why are my love stories full of all imaginable emotions except love?

And—is it so?

Then I found a story that I wrote more than 25 years ago, where I found love. It was set in a very remote village in Bangladesh, where the people were very poor, malnourished, illiterate, superstitious and simple, like primitives. A poor young man marries a poorer girl; they love each other more than anything else in the world, so they are happy despite abject poverty. And then, one day, the girl fell sick with some flu, and there was no doctor, no medicine, and the food they usually ate to survive, rice, was impossible for her because she lost her appetite.

Desperate to help his wife in any possible way, the husband keeps telling her, "You need to eat! You need to eat! What do you wish to eat?" She names a kind of small fish found in the paddy fields and small ponds around the village. The husband runs off with a fishing net in his hands and after a while, comes back with a few fish to find his beloved wife dead. But he doesn't cry; he stays silent for a while and then says to his dead wife, "Stupid woman! If you were going to die, why did you ask me to go fishing? Why didn't you say, stay beside me?" Then the night comes. He goes to bed, falls asleep, and dies.

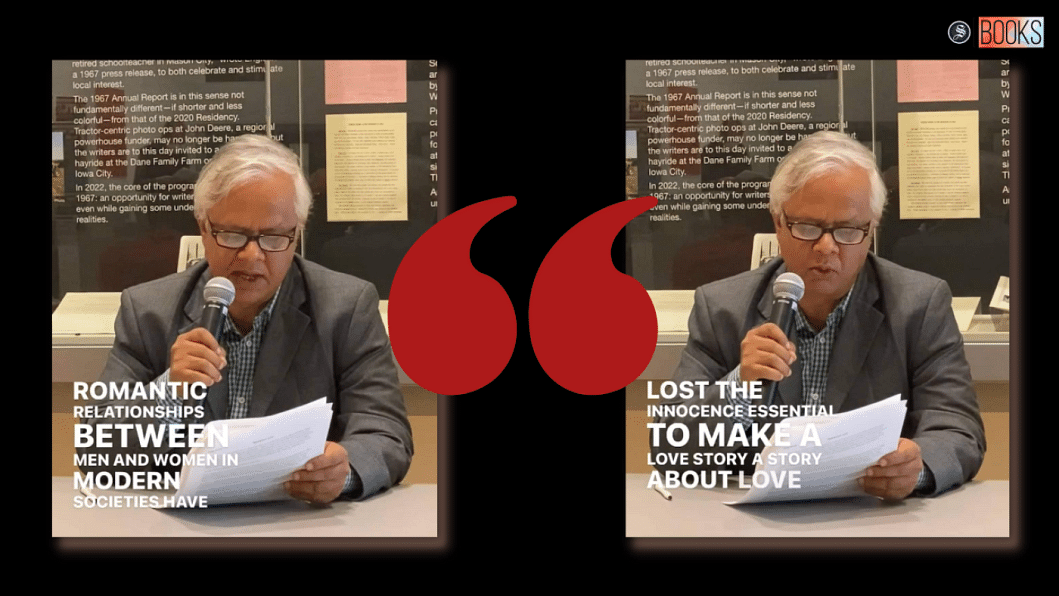

I think stories like this can only be imagined in those types of societies, where modernity has not yet reached, and the human soul has not been contaminated by "civilisation". Romantic relationships between men and women in modern societies have lost the innocence essential to making a "love story" a story about love in the true sense.

Edited by Shabnam Nadiya

Mashiul Alam is a writer, translator, and Senior Assistant Editor at Prothom Alo. He is currently a Writer-in-Residence at the International Writing Program (IWP), University of Iowa.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments