Probashi: Histories of the Bangladesh diaspora

The term diaspora originates from the ancient Greek dia speiro meaning a scattering of seeds. Originally used to represent the ancient Greek and Jewish exiles, "diaspora" is now used in general terms to refer to the movement and dispersal of people who affirm a shared identity based on their place of origin.

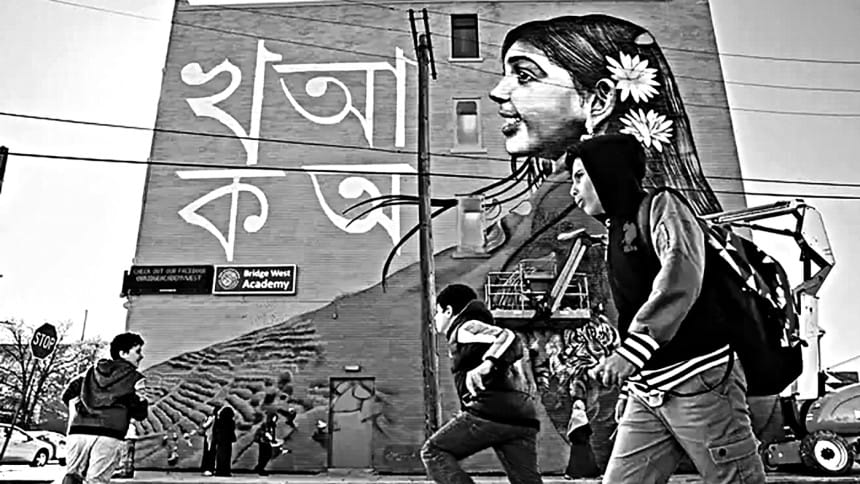

Movements across national borders are part of a regional history that predates Bangladesh as an independent state in 1971. The end of British rule over South Asia in 1947, accompanied by the partition of India, spurred one of the largest mass migrations in history, of an estimated fifteen million people. However, it is only after 1971 that we see the development of distinctively Bangladeshi international migration flows and settlements, defined by their relationship to and identification with Bangladesh as a nation. Since then, the Bangladesh diaspora population, also known as "probashi Bangali" or people from Bangladesh who live abroad has grown. From the Shaheed Minar Monument in Toronto, Canada, to the "Welcome to Bangla town" signs that greet people in Hamtramck, Michigan in the USA, the Bangladesh diaspora of today is a visible and influential presence in metropolitan areas throughout the world.

From 1947 to 1971, during the period of Pakistani rule, movement abroad was limited for people from present day Bangladesh because of the discriminatory practices of the Pakistani government including the routine denial of passports to the Bengalis of East Pakistan. Despite these constraints, the Pakistan era did see the development of a migration circuit between the region of Sylhet (Northeast Bangladesh) and Britain. The roots of this circuit lay in the nineteenth century history of young men from Sylhet who found work as lascars or sailors on British ships that carried out goods from the region. The experiences of these pioneering seamen created a culture of migration in the region with enduring social networks between Sylhet and Britain. In the post-WWII years, Bengalis moved to Britain as labor migrants and gradually established their presence by sponsoring family members to join them.

Starting in the 1980s, national and global forces converged to usher in an era of expanding international migration for Bangladesh. National policies became increasingly subject to international financial regimes and the principles of state-centered development were replaced by those of integration into the global market economy. A major component of these movements is labor migration directed largely towards the oil-producing GCC states -- Bahrain, Kuwait, Oman, Qatar, Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates. Since the 1990s, these destinations have expanded from the GCC to include a wider range of countries such as Malaysia, Singapore, Jordan and Lebanon. Hampering the growth of stable, multi-generational Bangladeshi diaspora communities in these societies are host country policies designed to prevent long-term settlement and integration and to ensure that Bangladeshi workers return home. Most Bangladeshis are recruited to work abroad on short-term labor contracts, often for low-skilled jobs in agriculture, construction and domestic service. With some exceptions for professional, entrepreneurial and skilled migrants, families are not permitted to join them. In these societies, citizenship is not automatically granted to those born in the territory and opportunities for naturalized citizenship are largely limited to the foreign wives of national men and. Foreign workers are generally prohibited from marrying locals.

Besides labor migration, a second stream of post-1980s international migration from Bangladesh has been towards the Global North, to Australia, Canada, Italy, the United States and other economically developed countries. A critical feature of the second stream, unlike the first, are the available opportunities in the destination societies for family migration and permanent settlement. Unlike the first, the second stream has also largely been of Bangladeshis with middle-class origins.

The independence of Bangladesh in 1971 resulted in expansion in the ranks of the middle-class due to a new growth of employment opportunities in the public administration sector. Since that time, the Bangladeshi middle class has grown and stratified to include professionals, business owners, and white-collar workers in the financial and retail industries and NGO sector. In a "brain drain" dynamic, Bangladeshis holding professional credentials and skills that are valued in the global market have migrated in response to lucrative and attractive employment opportunities that are far superior to what is available to them in Bangladesh. Family reunification laws have enabled them to sponsor family members to join them. Besides the possibility of better employment opportunities, the goal of acquiring globally recognized educational credentials for one's children drives these movements to the Global North. Of relevance also is the growth of middle-class consumption in early twenty-first century Bangladesh that is oriented towards the global market. As is the case in neighboring India as well as in other parts of the world, this "new middle class" as it is often called, is defined by its taste for globally branded goods, whether it is electronics or fast food. Under a neoliberal global regime, migration and settlement in the developed world has been informed by goals of upward mobility through a lifestyle that satisfies emergent consumption standards.

What will the Bangladesh diaspora of the future be like? Despite the increasingly restrictive policies of migrant-receiving countries, I am quite sure that the Bangladeshi presence abroad will continue to expand in size and breadth across different parts of the world. I am less certain though about how the diaspora, across its many diverse segments, will identify with Bangladesh and organize ties to the country in the years to come. Some of this depends on the state of governance and politics in Bangladesh, which will shape levels of trust in the country's institutions and confidence in its continued progress. These conditions have important consequences for how Bangladeshis abroad understand and act towards their country of origin. For example, pride in the country's progress and confidence in its future encourage the diaspora to maintain active ties with the homeland, and to invest and participate in its progress. Conversely, reports of corruption (often verified by frustrating personal encounters with government bureaucracies), human rights abuses, unsafe roads and declining democratic practices foster a desire to distance and disassociate with the country.

We can expect the diaspora policies of the Bangladesh state to have an impact on the relationship of expatriates to the homeland. Since the 1990s, Bangladesh has acknowledged the importance of the diaspora, especially of the remittances, for the country's economy; remittances are a major source of foreign earnings for Bangladesh. In 1990, the Wage Earners Welfare Fund, which requires contributions from each migrant worker, was set up to help migrant workers and their families in emergency situations such as illness, death or legal problems in the receiving countries. In 2002, the Ministry of Expatriates Welfare and Overseas Employment was created with the goal of facilitating labor migration, exploring new labor markets and ensuring the welfare of Bangladeshi migrant workers. Despite these efforts, successive governments have faced intense criticism for their failure to protect the most vulnerable less-skilled labor migrant citizens from the abuses of the labor migration system, especially from mistreatment by foreign employers and exploitation by recruiting agents.

With respect to the permanently settled diaspora population, the Bangladesh state has drawn inspiration from the much-heralded diaspora role in two of the world's most important growing economies – China and India. Like "NRI" (Non-Resident Indian) in India, "NRB" or "Non-Resident Bangladeshi" has emerged as an official category of identification, suggesting a particular connection and attendant privileges with respect to the Bangladesh state. These range from special NRB eligibility for certain kinds of foreign currency bank accounts in Bangladesh as well as the official waiver of Bangladesh visa fees and requirements for NRBs who are traveling to Bangladesh on a foreign passport. The Dual Nationality policy of Bangladesh, which allows those who are foreign citizens of Bangladeshi origin (as well as the children born to them) to become or to affirm their citizenship, has also institutionalized NRB status.

In recent years, expatriate demands for greater political rights in Bangladesh have grown. For example, segments of the diaspora have vigorously lobbied for dual nationals to hold the same rights and privileges as other citizens, including voting rights and eligibility to participate as candidates in local and national elections. These demands reflect the important role of diaspora communities in the politics of Bangladesh, whether through financial support of political parties and candidates, or the lobbying of foreign governments and bodies to support a particular cause. Political leaders in Bangladesh have expressed concern at various times (especially when they are in power) about the diaspora's undue influence through its international connections, on the political scene in Bangladesh.

Besides political and policy developments, I see the future of the Bangladesh diaspora to rest on the continued identification with the homeland of those who are of Bangladeshi origin but were born and/or raised abroad. Bangladeshis around the world have established local groups and associations that aim to facilitate and encourage the practice of cultural traditions as well as foster a sense of community among Bangladeshis. They organize social and cultural events, such as annual picnics, Bangladesh Independence Day celebrations, and cultural shows featuring celebrity singers and performers from Bangladesh. They may also hold Bengali language classes for children on the weekends and conduct fundraisers for charity and disaster relief efforts in Bangladesh. Communities also work to establish ties with local political representatives and authorities in an effort to gain recognition for community needs and support for projects ranging from introducing Bengali as a second language in public schools to permission for building mosques and community centers.

Another type of diaspora association is the HTA (Hometown Association) which brings together those from a specific locale in Bangladesh with the goal of fostering social ties among them and collectively engaging in good works back in the home community. There are also alumni associations based on affiliation with schools and universities in Bangladesh as well as occupation-based groups such as the American Association of Bangladeshi Engineers and Architects. The activities of these associations typically include annual meetings, newsletters, internet chat groups, and fundraising for scholarships in Bangladesh.

To what extent will the community organizations of the Bangladesh diaspora, initiated largely by people who were born and raised in Bangladesh, be successful in fostering a continued sense of identification with Bangladesh among the younger generations? In my research on second-generation Bangladeshis in the UK and the USA, I found a range of attitudes towards Bangladesh: of strong commitment to maintaining ties as well as rejection of them, with most falling somewhere in the middle of these extremes. In the context of a post-9/11 political landscape with its War on Terror policies and rampant Islamophobia, many young persons were inclined to prioritize their identity as Muslims over and above their Bangladeshi origins.

Over the course of over fifty years of independence, Bangladesh has shifted, from a region of limited to one of extensive overseas movements. The Bangladesh diaspora, composed of a diverse set of movements and settlements of Bangladeshis around the world, continues to grow and evolve.

Nazli Kibria is Professor of Sociology, Boston University, USA. Her books include Muslims in Motion: Islam and Identity in the Bangladeshi Diaspora (2011, Rutgers University Press).

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments