Dysfunctional political demonstrations and the disruption in daily life

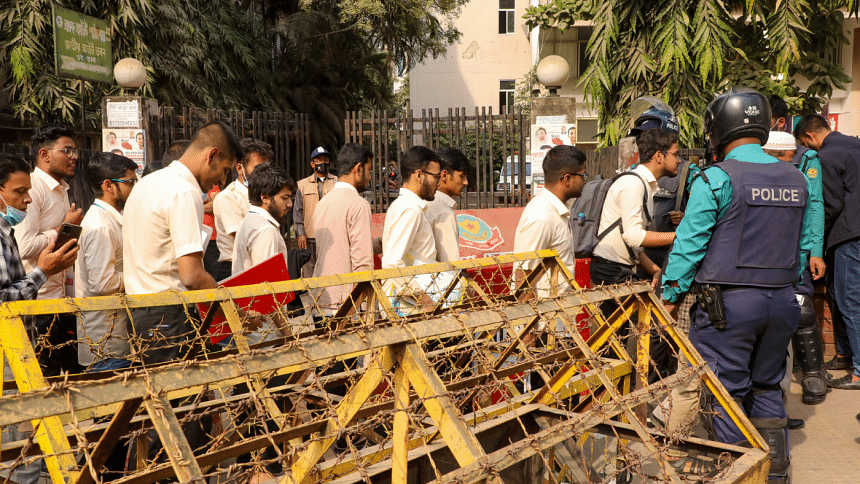

I stood in front of the Bijoynagar Water Tank as I saw a few policemen instructing shopkeepers in the area to close their shops. I immediately realised that I could not stand in the spot any further as political clashes continued to brew in front of the nearby BNP office.

I headed back home instead of going to my coaching for my Further Maths mock exam.

This was not the first time that I had to suffer due to political demonstrations in the capital. Being a resident of Paltan, it is very evident that my house is near some of the epicentres of political violence in the country, such as Shahbagh, Press Club, Suhrawardy Udyan, and the BNP office itself.

Given the nature of the political fabric we find ourselves stitched into, it is very obvious that there is a significant possibility of violence erupting from political demonstrations. However, the problems with political demonstrations are not just limited to the violence faced by those actively taking part in it, the onus of which is shared by both the ruling and opposition parties, but rather extend to the bystanders who find themselves in the middle of it, who end up getting hurt or face serious disruptions in their daily lives.

Why are political demonstrations like this? I think one of the most important points of origin of such disruptive political demonstrations can be traced back to the British colonial rule. Back in those days, the only way political dissenters could grab the attention of the British colonialists was to disrupt the government's functionality. Similar tactics were used against the Pakistani regime too. Therefore, the present scenario may be the lingering remnants of those very same methods.

While it is true that such methods worked back in those days, one cannot help but be extremely sceptical about their efficacy in the status quo. It seems to me that such political demonstrations are rather counter-productive as people are less likely to feel positively about a certain political party if they see that the party's men are causing road blockages resulting in commute delays, especially if people have not bought into the demands made in these demonstrations.

The established political parties and movements in our country have a multitude of methods to get their manifestos across, such as press conferences being broadcast in the national media. However, in a country where politics is largely based on showing off muscle power at the ground level, it is unlikely that politicians will have the incentive to be sensible enough to choose nuisance-free alternatives to national-level rallies.

While it is perfectly understandable for people to be agitated about the disruptions to public life caused by these demonstrations, I believe that exceptions have to be made. For movements such as the Road Safety Movement of 2018, exceptions can be made, as these protestors did not have malicious intentions nor the socio-political capital held by established politicians.

As the country heads into another election season, political demonstrations will definitely be on the rise and so will the number of disruptions in public life. To say that political parties will improve themselves in conducting peaceful demonstrations which do not cause public nuisance is a statement built entirely on hope. And hope, when it comes to the Bangladeshi political landscape, is not a wise thing to have.

Hrishik Roy is an intern at The Daily Star. Reach out to him at [email protected]

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments