Global diplomacy and the birth of Bangladesh

During their heroic Liberation War, the people of Bangladesh received much international sympathy for the terror unleashed on them by the Pakistan army, but little support for the cause of independence. Right up to November 1971, India was the only country to support the cause of an independent Bangladesh. The Soviet Union came on board at the end of November.

International opinion was reflected in the resolution adopted by the UN General Assembly on December 7, 1971. The resolution called for an immediate ceasefire, which would have halted the advance of the liberation forces. It was adopted by a massive majority of 104 votes to 11, with 10 abstentions. Only India, Bhutan and the Soviet bloc voted against the resolution.

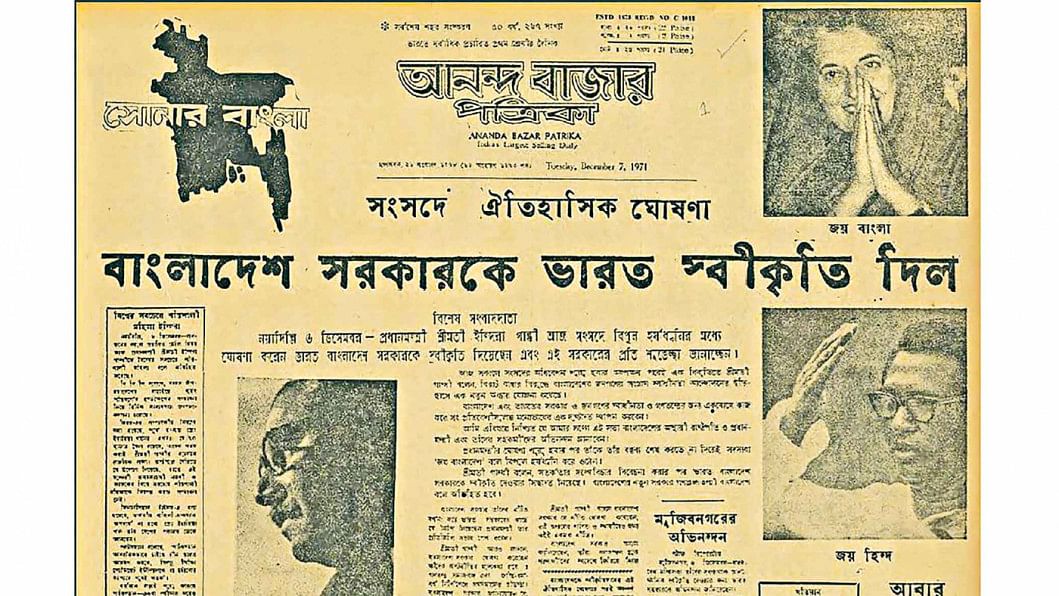

Before the Pakistani surrender on December 16, 1971, only two countries, India and Bhutan, formally recognised the People's Republic of Bangladesh. Others took months, or even years to follow suit.

Why did other countries not support the cause of an independent Bangladesh earlier? And why was India an exception?

Many Pakistanis believe that India had always intended to break up the old Pakistan and that it simply seized the opportunity that offered itself in 1971. The documentary evidence conclusively disproves this belief. Indian policymakers deeply sympathised with the legitimate demands of the Bengalis of the erstwhile East Pakistan but they hoped, right up to March 1971, that these demands would be met by a transition to democracy in Pakistan.

Thus, in a secret letter to New Delhi on December 2, 1970, India's High Commissioner in Pakistan, BK Acharya wrote: "Majority control of the Central Pakistan Government by East Pakistanis seems to be our only hope for achieving our policy objectives towards Pakistan and overcoming the stone- wall resistance of West Pakistan. In order that this may become a reality, however, it is essential that Pakistan (with its East Pakistan majority) should remain one…"

In early 1971, most Indian policymakers found it difficult to believe that Pakistan's military rulers could be so irrational as to launch a murderous onslaught against the majority population of their country – an onslaught that would inevitably trigger off a liberation war and lead to the break-up of Pakistan.

The question came to the forefront in early March when, on instructions from Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman, Tajuddin Ahmed met the Indian representative in Dhaka, Deputy High Commissioner Sen Gupta. Tajuddin asked whether India would offer political asylum and other support to freedom fighters in the event of a Pakistani crackdown. Maidul Hasan, a close associate of Tajuddin, informs us that New Delhi's response was that Indian officials were not convinced that a military crackdown was imminent but, if it were to be imposed, India would offer all possible assistance to the Bangladeshis.

The brutal military crackdown on March 25, 1971 produced a massive wave of public sympathy and support in India for the Bangladesh cause and demands that all possible assistance be given to the liberation movement. On March 29, the Indian parliament unanimously adopted a resolution voicing its "profound sympathy and solidarity with the people of East Bengal" and calling upon all countries to "prevail upon the Government of Pakistan to put an end immediately to the systematic decimation of people which amounts to genocide."

India decided to extend all possible help to the Bangladeshi freedom fighters to achieve victory as early as possible. New Delhi hoped for a friendly neighbour on her east. She also feared the possible spill-over effects of a long-duration guerrilla war across her borders. The Mujibnagar government was afforded the facilities it required and assistance was provided for training and equipping the Mukti Bahini. In April, following discussions between Indira Gandhi and Tajuddin Ahmed, a comprehensive plan was drawn up for Indian assistance in the Liberation War, leading up to a decisive victory before the end of the year.

In the diplomatic field, India had a two-fold objective: mobilising general support for the Bangladesh cause, and seeking the support of at least one of the two superpowers in the inevitable conflict that loomed ahead.

On March 29, India approached the UN Secretary general requesting him to take an initiative to "stop the mass butchery" in the erstwhile East Pakistan. The latter declined, explaining that UN member states insisted that the secretary general had no right to interfere in their internal affairs. This posed an "insuperable obstacle."

We must recall that, in the 1970s, the principle of humanitarian intervention had yet to find acceptance in international law and practice. The principle of territorial integrity of independent states was interpreted as excluding secession or breakaway of a territory. This interpretation was vigorously supported by most Afro-Asian states, which were populated by diverse ethnic, tribal or religious groups lacking an overarching national identity. No breakaway movement had succeeded since World War II. Katanga and Biafra were failed attempts. After the founding of the UN, Bangladesh was the first case of a successful breakaway state.

As noted earlier, the UN General Assembly called for an immediate ceasefire on December, 1971, in an attempt to halt the progress of the liberation forces. Some of the 110 countries voting in favour – in particular, China, USA, and certain Middle Eastern countries – were motivated primarily by their close political ties to Pakistan. Others voted to uphold the principles of territorial integrity and non-interference, as interpreted at that time.

The liberation cause found a more receptive audience in liberal democracies, which had a free press and active human rights NGOs. There was a great deal of public sympathy for the people of Bangladesh in many western countries. Though none of them were prepared to support the cause of an independent Bangladesh, UK, Australia and New Zealand did, at least, call for an end to the bloodshed and a return to negotiations between Islamabad and the Awami League. Even in Nixon's United States, public and congressional opinion restrained the White House from supplying arms to Pakistan.

In its search for the support of the superpowers, India received an early favourable signal from the Soviet Union. On April 2, Moscow conveyed to Yahya Khan its "great alarm" over the crackdown in East Pakistan. However, India received a mystifying response when it sounded the Soviet Union on its readiness to share the burden of supporting the liberation struggle. Moscow's cryptic reply was that there were "unused possibilities" for further strengthening Indo-Soviet ties! It later became clear that this was a reference to the 1969 Soviet proposal for an Indo-Soviet treaty, on which India had been dragging its feet.

The quest for US support ran into an unsuspected obstacle. Without the knowledge even of the State Department, Nixon and Kissinger were secretly planning a dramatic breakthrough in US-China relations, using Pakistan as a channel of communication. The implications of this "geostrategic revolution" became apparent in July, after Kissinger's visit to Beijing, via Islamabad. Sensing an incipient US-China-Pakistan axis, India invoked the countervailing power of the Soviet Union. The Indo-Soviet Treaty of Peace, Friendship and Cooperation was signed on August 5.

Moscow was prepared to turn a blind eye to India's clandestine support to the Bangladesh freedom fighters but, even at this stage, it was opposed to open intervention. Moscow still hoped for a political solution within the framework of a united Pakistan. India perceived an opportunity to change the Soviet perception when, in September, the Mujibnagar authorities formed a United Front, including the CPB and other leftist parties, and also opened up recruitment of CPB and NAP(M) followers to the Mukti Bahini. Indira Gandhi flew to Moscow at the end of the month and succeeded in at least partly convincing the Soviet leaders that the Bangladesh struggle was a "war of national liberation" as defined in the Marxist lexicon. By the end of November, this was fully accepted by Moscow.

On December 3, Pakistan attacked India's air bases in the west, triggering off a war for which India had been readying itself since April. As anticipated, the US tried to deny a decisive victory to the liberation forces through a Security Council resolution imposing an immediate ceasefire and troop withdrawals. These attempts were thwarted by the Soviet veto. Nixon's attempt to "scare off the Indians" by sending the nuclear- powered aircraft carrier USS Enterprise into the Bay of Bengal met with a defiant response from India. The Liberation War ended with the unconditional surrender of the Pakistani occupation forces on December 16, 1971 – a glorious day in South Asian history.

Chandrashekhar Dasgupta is the author of, "India and the Bangladesh Liberation War."

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments