Women photographers of the Bangladesh Liberation War

War and women – this phrase usually conjures up an image of women being victimised during war, but there are activities of women, fighting on the battlefield, or even capturing photos with a camera in hand, which represents that time.

The 1970s were a time of global turmoil, during which the media had to select their stories based on the gruesomeness of the event. The Vietnam War took up most of the attention of Western media. Bangladesh made headlines only after the devastating cyclone in 1970 left half a million people dead.

Bangladesh declared independence on March 26, following a brutal operation of the Pakistani army on March 25, 1971 during which they killed intelligentsias, students and East Pakistani Regiments of the armed forces. A million people were displaced from the country within a month. News of the military operation spread across the world but as journalists were denied entry into the country, it was difficult to provide authentic news to the world. Going into the war zone posed great risks as well, since the Pakistani Army was ruthless and refused to maintain the protocols of war.

As the military operation spread across the country, approximately 10 million people were forced out of the country and took refuge in India. In September 1971, "Carry on Dying" and "Can the Refugees Ever Go Home?" were headlines in British newspapers. Testimonies from the refugee camps largely shaped opinions about the war, which was still out of reach of photojournalists. However, there were a few brave photojournalists who were desperate enough to report from the war zone.

At that time, there were technical limitations as well. Photographers had to come out from the war zones to send their films to their agencies for publication as quickly as possible. If they wanted to do a story, they had to type it up, go to the telex operator and ask them to telex it.

This piece is a tribute to a group of individual women photographers who stood their ground, broke social norms, and paved the way for future generations to provide us with glimpses of history through their iconic images of an unrecognised genocide.

Sayeeda Khanam

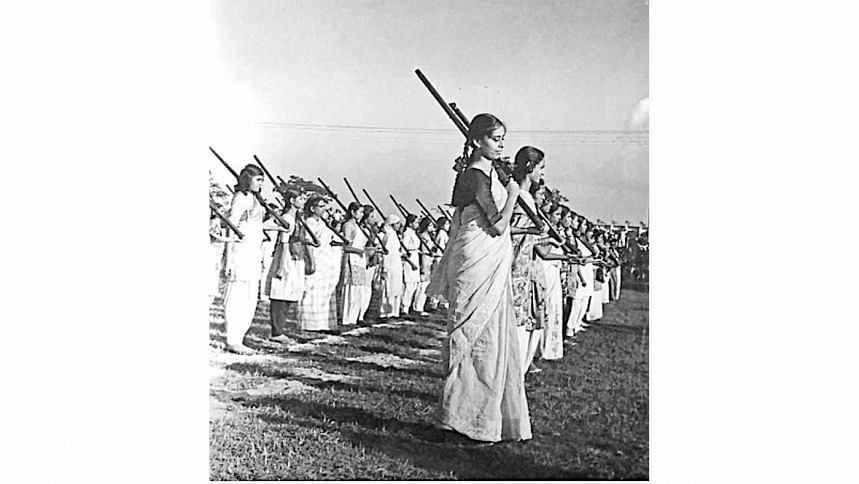

One of the most widely-known photographs of women freedom fighters, showing a group of women in sharees, rifles in hands, undergoing combat training, was taken by Sayeeda Khanam.

She took this photo just before the war began, at Azimpur Girls' School, a makeshift training camp at the time. But the irony is that she could not take a single photo during the nine-month war, she was stuck in Dhaka. This is what she calls her biggest regret in life. In a 1972 essay, published in the weekly magazine Bichitra, Khanam wrote: "I think I failed in every aspect miserably. I could not take a single picture in these nine months. The helplessness frustrated me each and every moment in that time. If only I had better equipment – a telephoto lens and few colour negatives, I could record a bit of the history of these nine months even after being stuck on the second floor of a building."

When news broke out of Bangladesh's victory, she went out with her camera and only one roll of medium format film. She was photographing freedom fighters in front of Hotel Intercontinental, where a crowd was cheering them on. All of a sudden, shots were fired into the crowd. Khanam sought shelter in a nearby house while other spectators fled the scene. After a few hours, she attempted to return to the same place to take photos, but got caught in the crossfire in front of the hotel. Fortunately, she survived, unharmed. One of the photos she took on that day was of the Muktibahini on the roof of a bus, and of the dead body of a soldier found near Ramna Park.

After the return of Sheikh Mujib in 1972, the students of Azimpur Girls School gave him a guard of honour, which was covered by Sayeeda Khanam. She also worked as a volunteer nurse at Holy Family Hospital, photographing child victims who were wounded in a grenade explosion. According to her lifelong friend Aleya Ferdousi, Khanam rescued and rehabilitated four female war victims from the Azimpur China building. She kept regular contact with the women who had been tortured during the Liberation War.

Photographer Golam Mustafa (1940-2021), recipient of the Ekushey Padak, recalls seeing her courageously working at a political procession in Sadarghat, despite being warned by her male counterparts not to go there. Consequently, she lost her glasses, sandal, camera strap, and her sharee was torn, but she did not care about such risks.

Khanam befriended legendary filmmaker Satyajit Ray after she met him in 1962 for an assignment for the magazine Chitrali. She later worked on three of Ray's films

("Mahanagar" in 1963, "Charulata" in 1964, and "Kapurush" in 1965) as a still photographer. Her book Amar Chokhe Satyajit is about her time and experiences with the filmmaker and his family.

Sayeeda Khanam was the first female, Muslim professional photographer of Bangladesh. She was born on December 29, 1937 in Pabna district. In 1956, she began her career as a photographer for Begum, the only newspaper dedicated to women at the time. In her photographs, we find such intimate moments as Sheikh Mujib visiting his ailing father in PG Hospital, national poet Kazi Nazrul Islam with his wife Promila Devi, and of classical musician Annapurna Devi taking lessons from her father, maestro Ustad Baba Alauddin Khan. She also photographed Mother Teresa, master painter Zainul Abedin, and Queen Elizabeth II's 1966 visit.

Recipient of the Ekushey Padak in 2019, Sayeeda Khanam passed away on August 18, 2020.

Anne de Henning

"I don't think you can ever get desensitised to images of war because they're always about separation, death, destruction… the same pictures and the same awful results of what fighting brings upon the civilians, and also, of course, the fighters. So, I don't think anyone should be desensitised. I don't think anyone can get desensitised."

These words were spoken by French photojournalist Anne de Henning, born in Paris in 1945, who is among the few women photographers to have witnessed the conflicts in Vietnam and Bangladesh. She was the only female photographer who travelled to East Pakistan in April 1971, during the early stages of the war.

In March 1971, de Henning had been photographing in Nepal when she read in the news that fighting had erupted in Dhaka. At that time, the Pakistani authorities were not letting foreign journalists into the country, obviously to keep them from reporting on the atrocities against the civilian population. Upon hearing this, de Henning felt compelled to fly to Kolkata to try and get into East Pakistan and share with the world what was happening. After several failed attempts to cross the border near Kolkata, she teamed up with three colleagues: photographer Michel Laurent, AP correspondent Dennis Neeld, and CBS correspondent Patrick Forest. They hired a beat-up car, loaded it with three jerry cans of petrol, reached the border with East Pakistan further north on April 6, and managed to convince the border security forces to let them in.

On the way, they witnessed crowds of people getting ready to fight, but the streets were eerily empty and a lot of refugees were crowding at the station. People had also come to see the journalists on the train to share the news and appeal for help. They travelled all the way to Rajbari, guarded by the Mukti Bahini. But on the night of their arrival there, the Pakistani army was crossing gunboats to the Padma River, which posed a huge risk to them being caught and held. De Henning aimed to go in with precision and leave immediately to get the news out. She decided to return to Kolkata on her own after a week. Her colleagues gave her their films and articles.

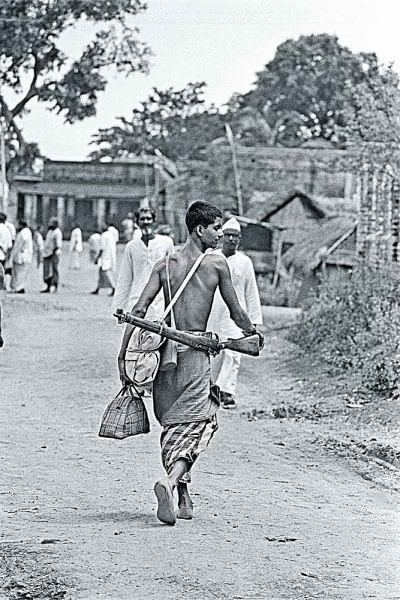

One of her signature photos, which has been widely circulated, depicts a bare-chested freedom fighter with an old British 303 rifle over his shoulder, wrapped in a lungi, walking briskly to join his combat unit.

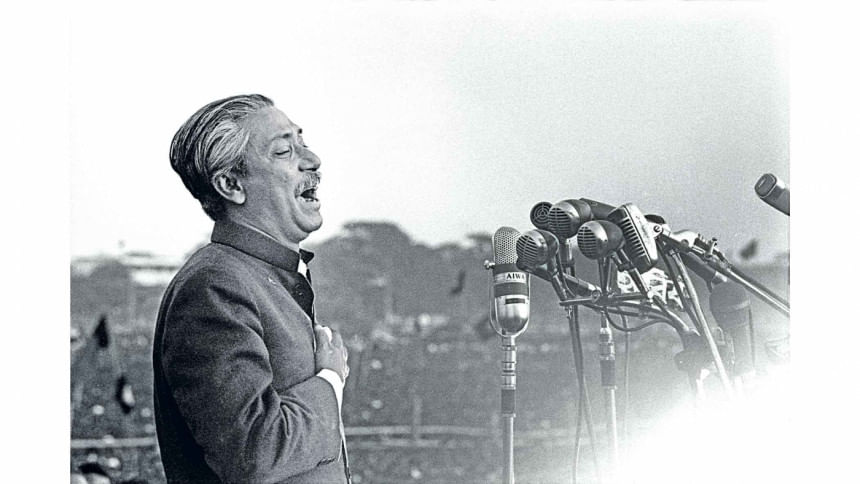

She flew back to Bangladesh from Kolkata in April 1972, as she wanted to return to the free country and cover Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman's speech, where she produced some rare portraits of him in colour, in which prominent national leaders such as Tajuddin Ahmed can be seen beside him.

Penny Tweedie

Penelope Tweedie was born on April 30, 1940, in a farming family in Hawkhurst, Kent. She studied photography at the Guildford School of Art from 1958 to 1961 under the legendary Ifor Thomas. Her first work was with Queen Travel Magazine in 1961. Two years later, she quit to pursue a freelance career, setting her own socially concerned assignments, which included covering homelessness, teenage pregnancy, and alcoholism.

She spent four decades working for charities and non-governmental organisations but suffered disappointments professionally, such as when the offer of a prominent staff position on the Daily Express was retracted after the British National Union of Journalists said it would be unthinkable to send a female photographer to a train crash.

After being turned down for commissions to cover the crisis in East Pakistan, British photojournalist Penelope Tweedie interestingly set out to photograph Air India's in-flight meals at their Heathrow kitchens in exchange for a ticket, and made her own way to Kolkata in 1971.

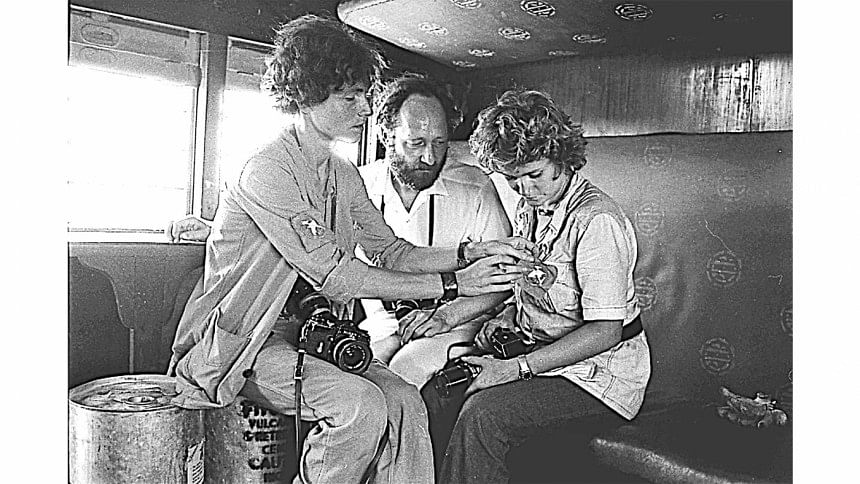

Once there, she was hired by The Sunday Times. Tweedie and a number of her coworkers (Simon Dring, Philip Jacobson, Bob Whittaker and Peter Gill) met in December and crossed into East Bengal by rickshaw, but they were detained as spies and imprisoned in a Kolkata jail. Once freed, all of them were photographed together by William Lovelace. She borrowed cameras after being freed, and the images she published of the war in Bangladesh depicted the suffering of refugees, as well as the bodies of Bengali intellectuals who had been killed by the retreating Pakistanis.

She worked extensively in the refugee camps. The suffering of women and malnourished children was portrayed vividly in her work. One of her photos of a dog digging out corpses from shallow graves was synonymous to the testimony provided by Friends of Liberation War Honour recipient volunteer Anjali Lahiri (1922-2014). Tweedie worked briefly in Khulna, then travelled to Dhaka with the joint forces of Mukti Fouj and the Indian Army. She visited Rayerbazar, where the mass killing of intellectuals by the Pakistani army and Al-Badr took place.

In one of Marc Riboud's photos, Tweedie is seen taking photos of the surrendered Pakistani army in Dhaka. When Bangabandhu came back to Bangladesh, she was there alongside other photographers.

On December 18, 1971, a victory rally at Dhaka Stadium put Tweedie in an unexpected position that would affect her professional career. A few Mukti Bahini irregulars started jeering at a number of prisoners who Tweedie accurately surmised would be executed for the benefit of the international press. She did not want to capture this horror, but the two photographers who stayed went on to win the Pulitzer Prize for their photos. The Sunday Times terminated her contract the following day, which may have been a coincidence. That incident followed Tweedie for years, but she never regretted following her heart.

Tweedie was her own worst critic, and photojournalism was her passion. She took her own life on January 14, 2011. It appears she was dejected about the lack of chances in her chosen field. The National Library of Australia acquired her entire library in 2013, which was its first acquisition of the lifetime work of a female photographer.

Marilyn Silverstone

Born in London in 1929, Silverstone began to photograph professionally as a freelancer in 1955, working in Asia, Africa, Europe, Central America, and the Soviet Union. She became an associate member of Magnum Photos in 1964, a full member in 1967 (as one of the only five women members), and a contributor in 1975.

In 1959, she was sent on a three-month assignment to India, but ended up moving to New Delhi and was based there until 1973. During that time she produced a number of books, including "Bala: Child of India." In 1970, Silverstone covered the local inhabitants who survived the devastating cyclone and the tidal wave at Charkukri Mukri island of Bangladesh.

When the war broke out in 1971 and people took refuge in bordering areas, she visited Salt Lake camp hospital in Kolkata, Haringhata camp, Helencha camp, Chandranathpur camp near Silchar, Bagchara Camp in 24 Parganas, the transit camp at Agartala airport and camps near Siliguri, and took photos of the crowded camps and skeletal children. The heartbreaking stories of motherless, undernourished children and people lying in makeshift hospital beds during the cholera epidemic, and the perilous journey of refugees, were graphically portrayed in her work.

She also visited the Liberation Army training camp in the eastern sector of Bangladesh, where 600 volunteers, schoolboys, village youths and shopkeepers received training to use machine guns and light machine guns. Post-independence, she travelled to Dhaka in 1972, when Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman addressed the biggest rally ever held at the Ramna Race Course. There, she produced an iconic portrait of Bangabandhu crying while addressing the nation.

From photographer Amiya Tarafder's view, we can see Marilyn standing in the back of Penny Tweedie and Rashid Talukdar sitting on the left. Interestingly, Silverstone also took photographs of paintings made by children who went through the trauma of war and painted some horrifying images of the Pakistani army's torture.

Silverstone, whose photographs have appeared in many major magazines, including Newsweek, LIFE, Look, Vogue, and National Geographic, became an ordained Buddhist nun in 1977. In 1999, she returned to the US for cancer treatment. She died in the same year in Shechen Monastery near Kathmandu, which she had worked to establish and maintain.

Mary Ellen Mark

Mary Ellen Mark was an American photographer born on March 20, 1940 in Pennsylvania. She began photographing with a Box Brownie camera at age nine. She joined Magnum Photos in 1977 and left in 1981, joining Archive Pictures. In 1988, she began her own agency.

Like Sayeeda Khanam, Mary Ellen Mark was also a unit photographer on movie sets, shooting production stills of more than 100 movies, most notably Francis Ford Coppola's Apocalypse Now (1979) and Baz Luhrmann's Australia (2008). For Look magazine, she photographed Federico Fellini shooting Satyricon (1969).

Mark was well-known for establishing strong relationships with her subjects. She published her famous book "Falkland Road: Prostitutes of

Bombay" in 1981, after spending 10 years building connections before starting work. She published 18 books of photography and contributed to publications such as LIFE, Rolling Stone, The New Yorker, The New York Times, and Vanity Fair. She produced her first book, "Passport" in 1974, which contains, among others, photos of the Bangladesh Liberation War of 1971.

Mark entered Bangladesh after Pakistan declared war on India in December in order to divert attention away from their atrocities in Bangladesh. Her notable photographs portray a very young freedom fighter with sunken eyes, sitting in the back of a truck with a gun, a defeated Pakistani army sergeant standing in front of the table of surrender in Khulna, and collaborators being captured in Khulna. Although her companions took photographs of dead bodies, no such photos can be found in Mark's work.

In an interview for this article, David Burnett said that Mary Ellen Mark was travelling with photographer Jack Garofalo from Paris Match magazine. She entered the country with the support of the Indian Army. He met them in Jessore and travelled to a newly liberated town in Jessore (Jhikorgacha).

Mark was transparent with the subjects of her photography, about her intent to use what she saw in the world for her art. She once said, "I just think it's important to be direct and honest with people about why you're photographing them and what you're doing. After all, you are taking some of their soul." She died at the age of 75 on May 25, 2015 in Manhattan. The Mary Ellen Mark Archives currently hosts two million images.

Marilyn Stafford

Marilyn Stafford born in Cleveland, Ohio in the US in 1925. Her photographic career was formally launched in 1948, when she took her first portrait of Albert Einstein for friends who were making a documentary film about him. She worked mainly as a freelance photojournalist based in Paris in the 1950s and early 1960s, and then in London, travelling to Lebanon, Tunisia, India, and many other places.

On a ferry crossing to England in 1949, Stafford had a chance encounter with Indian writer Mulk Raj Anand (1905-2004). He became Stafford's life-long friend and introduced her to Henri Cartier-Bresson, who was to become her photography mentor in Paris.

In 1971, through Mulk Raj, Stafford was invited by the then Indian Prime Minister, Indira Gandhi, to do a photo essay entitled "A Day in the Life of Indira Gandhi."

In early 1972, Mulk Raj was concerned about the fate of some of his Bengali writer friends, and Stafford accompanied him on a trip to Bangladesh to cover the aftermath of the Liberation War. On that trip, she photographed Sheikh Mujibur Rahman in Dhaka and took a helicopter to his village home, which was ravaged by the Pakistan Army. Her photographs portrayed one framed photo of Rabindranath Tagore, broken by the army when they were shattering everything onto the floor. They went on to plunder and burn villages.

One of Stafford's photos is of a destroyed village in Gopalganj, filled with burnt trees. As she visited the war-torn villages, her photos gave a glimpse into how people got back on their feet with new houses being built, the few available buses on the Mymensingh-Tangail route being heavily overcrowded, boats sailing on the river ,and people slowly going back to their homes and their lives. Some were not so lucky. Many villagers were killed and Stafford also saw some women who were in severe shock.

Stafford was motivated to capture the destruction left by the war. But, more importantly, she wanted to tell the stories of those who were physically and emotionally scarred by it, particularly the girls and women whom the Pakistani Army had raped.

Stafford was contacted by Salma Chowdhury, who had set up numerous shelters for women in need in Bangladesh. Thousands had been tortured, raped, and widowed by the Pakistani military and their local allies. Nari Punorbason Kendra (Women's Rehabilitation and Welfare Centre) was founded at Eskaton Garden in Dhaka, and Stafford visited the Centre in 1973. After she returned to England, she published the story in The Guardian and raised GBP 5,000 to send to Bangladesh to help the raped women get abortions. She later spoke on how she felt she "didn't do things so much photographically but did make a humanitarian contribution."

Marilyn Stafford had also taken photographs of paintings made by children for an exhibition organised by Kachi Kachar Mela, which spoke of the genocide and resistance during the Liberation War. The exhibition was later brought to the Commonwealth Institute in London by Bangladeshi master painter Zainul Abedin, who said, "We, the adult painters, have failed so far to treat the genocide and resistance on our canvases. These children have opened a new and fresh vision for us." Marilyn played an important role in organising this exhibition.

When she got back to London she was offered a staff post in a leading international fashion newspaper, which she turned down as she could not face living in the fashion world full time after what she had witnessed in Bangladesh.

Stafford has published three photobooks. One of them, Marilyn Stafford: A Life in Photography (2021) contains a chapter titled "The Aftermath of Bangladesh Liberation War." She set up the Marilyn Stafford FotoReportage Award to support women photographers for solution focused documentary photographic projects. In 2020, she was awarded the Chairman's Lifetime Achievement Award 2019 at the UK Picture Editors' Guild Awards in London.

----

I hope that, beyond this list, we will be able to explore the fascinating lives and works of more women photographers from the Liberation War period. There are still thousands of photographs from that period in possession of local private archives. As photographs provide strong historical evidence, it is essential that thorough research is conducted on those from 1971.

The women photographers gave us an insight of the female gaze during the Bangladesh Liberation War. Their work with the women and children in refugee camps displayed intimate and personal connectivity with their subjects. The fact that many came to Bangladesh of their own accord reflects their determination. Penny Tweedie suffered for her ethical stand in photojournalism. Anne de Henning, who was one of the first photographers to visit the free zones of Bangladesh, produced one the first colour photographs of the Bangladeshi flag which was presented to her. She also took some of the few colour photographs of Bangabandhu. While most of the photos taken during the Liberation War period are gritty, high contrast black and white representations of destruction and human misery, Marilyn Stafford's colour photographs show the resilience of the people of Bangladesh. They are like the transition from a grim, dark past to a vibrant future.These visual records by the women photographers are evidence of the undeniable genocide against a people, and a strong reminder of the need to hold onto hope.

Some of their roles actually went beyond photojournalism, as they helped put the word out by providing statements and worked closely with the rehabilitation of victims of war. It would be an injustice to them if their contribution is judged by only their photographs. Behind those lenses, the eyes of the beholder have stories to tell.

Amirul Rajiv is an art historian, curator and co-founder of Duniyadari Archive.

PS: Writing about this issue led me to contact people around the world and go through visuals and records at that time. The testimonies of the people portrays the level of sacrifice people at home and abroad had to make for the freedom of our country in 1971. I want to thank the following people and organisations for their support and contribution:

Anne de Henning, Marilyn Stafford, David Burnett, Shaheen Akhter, Paramita Muller Lahiri, Surajit Lahiri, Bharati Dasgupta, Lorène Durret of Association Les amis de Marc Riboud, Naim Ul Hasan of Duniyadari Archive, Lina Clerke & Nina Emett of Marilyn Stafford Photography, Michael Regnier of Panos Pictures, Ruth Hoffmann & Georgina Dallas of Magnum Photos, Mary Ellen Mark Archives, Ain o Salish Kendra, Shechen Monastry, Shamsuzzoha Sajen of Bangladesh on Record, Mofidul Hoque & Amena Khatun of Liberation War Museum, Ruxmini Reckvana Q Choudhury of Samdani Art Foundation, Shameema Binte Rahman of rottenviews.com, Nafeesa Shamsuddin, Pavel Partha, Anil Mandal.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments