Doing journalism and telling the truth: Zahur Hossain Chowdhury’s ways

Among the editor-journalists in our country, one of the most famous names undoubtedly is Zahur Hossain Chowdhury (1922-1980). Syed Najmuddin Hashim, a close friend of Zahur Hossain and an erudite writer and former diplomat, referred to him as 'the nucleus and the life-force of East Pakistan's giant editor-trio,' which also included Manik Mia and Abdus Salam. Zahur Hossain began his career in journalism at the famous literary journal Bulbul, edited by his cousin Habibullah Bahar Chowdhury and Samsunnahar Mahmud, before joining The Statesman as an apprentice journalist in the 1940s.

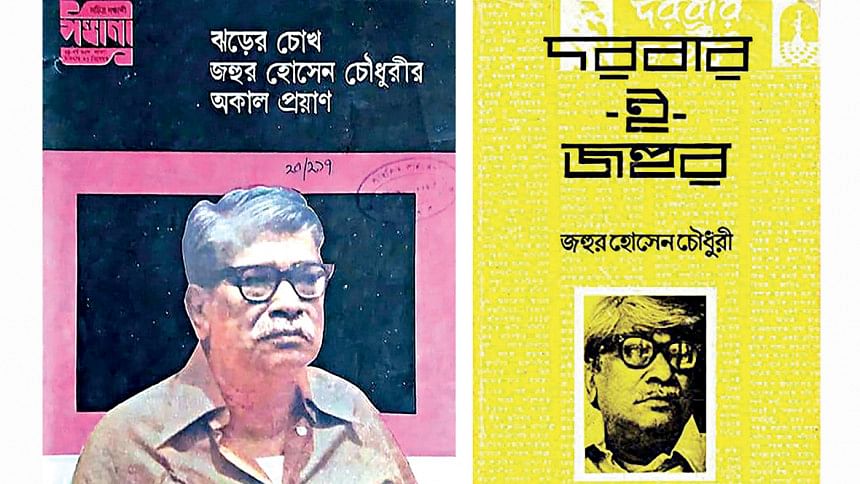

Immediately before and after partition, Zahur Hossain Chowdhury worked in various capacities at Weekly Comrade, Star of India, Azad, and Pakistan Observer. But his name became synonymous with Sangbad, a newspaper where he joined in 1951 and later became editor in 1954, a position he held until 25 March 1971 when the newspaper was burned to ashes by the Pakistani military. Zahur Hossain Chowdhury's reputation reached legendary heights during his lifetime due to his courage, incisive writing, and commitment to free journalism and democracy. On the centenary of his birth, a careful examination of his extraordinary and prolific career reveals that all the attributes attached to him go far beyond their ordinary meanings.

Under his editorship, Sangbad's role extended far beyond simply depicting what was happening in society. Through his fiery editorials, penetrating commentaries, and informed analysis, Zahur Hussain Chowdhury played a significant role in shaping public opinion and influencing the political trajectories of his time. Particularly in the 1960s, Zahur Hossain was an important catalyst in the emergence of student power, workers' and peasants' movements, and the resurgence of demand for democratic reforms in East Pakistan. His writings on the issue of economic exploitation and the cultural rights of Bengalis, supported by factual examples from history and rationalism, provided the people of East Pakistan with the means to fight for their rights.

Through Sangbad, Zahur Hossain gave voice to the discrimination against East Pakistan, the underrepresentation of Bengalis in armed forces and central government jobs, and the overall question of political, cultural, and economic autonomy for East Pakistan.

While Ittefaq represented one strand of the struggle of the people of East Bengal, Zahur Hossain Chowdhury's Sangbad represented another. In addition to addressing issues affecting Bengalis in general, he facilitated the voices of the struggles of workers and peasants.

Sangbad actually served as a popular mouthpiece for class-based politics in East Pakistan. If we want to discuss Zahur Hossain Chowdhury's contribution to the cultural flourishing in East Bengal during the 1950s and 1960s, we must also recognize the role played by the newspaper he edited, through its literary, cultural, and children's supplements. In addition, he played a key role in organizing culturally and historically significant Pohela Boishakh celebrations in the 1950s and Tagore's birth centenary in the 1960s.

Doing journalism, let alone being an editor, in Pakistan, a country that was frequently ruled by military dictators or military-backed governors, was a dangerous and difficult job. The dangers and difficulties of this profession came more from external factors rather than the inherent hazards of the business.

The repressive Press and Publication Act (which changed in different versions over time) always hung like a sword of Damocles over a journalist's head, and editors were frequently served with lists of dos and don'ts.

A popular and influential newspaper like Ittefaq was shut down, and its editor Manik Mia – whom Zahur Hossain Chowdhury greatly admired and affectionately called 'Manik Bhai' – was imprisoned. While Zahur Hossain Chowdhury did not have to go to jail during the Pakistan era, he did have to deal with a couple of defamation cases (he was ultimately arrested in independent Bangladesh in 1980, a few months before his death).

As an ardent believer in democratic values in every aspect of life, Zahur Hossain Chowdhury never hesitated to speak truth to power when it came to freedom of the press and speech. He not only expressed his views through his fiery writings and commentaries, but he was also actively involved in organizing journalists to defend untrammeled journalism. He was one of the founders of the East Pakistan Press Club and the East Pakistan Journalist Association.

As he was known for his trustworthiness and expertise in history, literature, and politics, Zahur Hossain Chowdhury was also famous for his wit, quick wit, and skill in using expletives (which he only used in private). In personal encounters with self-assured and patronizing civil and military bureaucrats and politicians on issues that pitted East and West Pakistan against each other, Zahur Hossain Chowdhury never hesitated to use his sharp intellect and biting words.

There are descriptions of many such encounters, including some with Pakistan's 'Iron Man' Ayub Khan, in Zahur Hossain Chowdhury's own writings and the recollections of his contemporaries. For example, in response to Ayub's insinuation that he had allegedly taken money from a certain embassy to celebrate Tagore's birth centenary, he said, 'I do not sell my soul at such a cheap rate.' Najmuddin Hashim wrote that one of Zahur Hossain Chowdhury's weapons was 'thoughtful buffoonery', through which, like the fools in Shakespeare's plays, he spoke uncomfortable truths.

Zahur Hossain Chowdhury's criticism was not limited to the West Pakistan-based ruling clique and their local Bengali agents. He had the ability to go beyond the easy task of laying all the blame on the obvious culprits. He consistently criticized the leaders of democratic movements for their shortsightedness, disunity, and unhealthy competition for power and positions, which he argued often paved the way for authoritarian rule in Pakistan.

Despite his deep respect and personal friendship with national leaders like Fazlul Haq, Suhrawardy, Maulana Bhasani, and Sheikh Mujib, Zahur Hossain Chowdhury did not hesitate to criticize them.

One example from the 1965 presidential elections can be cited here, where Fatima Jinnah, the candidate of the Combined Opposition Parties of Pakistan (COPP), ran against Ayub Khan. Despite unprecedented enthusiasm for the opposition candidate, Fatima Jinnah received 49% of the vote share in East Pakistan and 20% in West Pakistan. Zahur Hossain Chowdhury believed that Bhasani's sudden abstention from campaigning for Miss Jinnah was responsible for her not gaining a majority in East Pakistan. He criticized Bhasani for leaning towards Ayub at this time, stating that if the opposition candidate had won a majority in East Pakistan, the democratic movement would have been intensified in East Pakistan.

It is also worth noting that his opposition was directed towards the limited and constrained nature of democratic movements and demands. He did not hesitate to say that the leaders of the democratic movements, by democracy, mostly understood elections and capturing power. Without downplaying the importance of elections, Zahur Hossain pointed out the pitfalls of such a narrow understanding of democracy. To him, democracy meant something more than what his contemporary political leaders understood it to be. To illustrate this point, I want to draw readers' attention to his writings and activities during the riots of 1964 throughout East Pakistan.

The riots of 1964 began in Khulna in the first week of January against the backdrop of the Hazrat Bal incident in Kashmir and the India-Pakistan tension. Soon after, in a familiar pattern, as refugees started to pour across the border, riots broke out in Kolkata and its surrounding areas. Before the Kolkata riots could be fully contained, the most violent and widespread riots since 1950 engulfed all of East Bengal, with the worst of it occurring in Dhaka, Narayanganj, and Joydevpur.

The resistance to the 1964 riots demonstrated the power of solidarity in the face of communal frenzy. Journalists, intellectuals, students, and political leaders not only condemned the government but also confronted the rioters in many places by forming peace committees. Ordinary citizens heroically risked their lives – a few were even killed – in trying to save their Hindu neighbors, friends, and colleagues.

Among journalists, Zahur Hossain was at the forefront of the resistance. At a time of heavy-handed censorship, Zahur Hossain, shortly after the outbreak of the Khulna incidents, cautioned everyone – especially the progressive leaders of East Bengal – about the danger of communalism and the urgent need to resist it. While others remained indifferent, he wrote about it and even went so far as to reprint an essay written and distributed by Jasimuddin during the 1961 riots that affected some northern districts in both Bengals. He also immediately organized other editors and journalists to issue a joint statement condemning the riots and urging the government to take necessary steps.

But Zahur Hossain Chowdhury, in his characteristic manner, saw the other side of the issue. Even before the anti-Hindu riots could spread beyond Khulna, he addressed the issue in a series of articles titled 'The Weakness of Our Democratic Movement,' identifying the weaknesses in the ongoing struggle for democracy.

Zahur Hossain Chowdhury had no illusion about the government's involvement in the riots. However, he also noticed that the pro-democracy progressive forces had not taken the issue of communalism seriously enough. He saw this aversion to confronting the issue of communalism as a "fundamental weakness of our democratic struggle."

The riots began on January 3 in the afternoon, and the news reached Dhaka that night. Zahur Hossain Chowdhury wrote that no leader bothered to rush to the terror-stricken Khulna. The following day, the leaders of the National Democratic Front, a coalition of major pro-democracy parties including the Awami League, met in Dhaka and made some important demands, but did not mention the ongoing riots in southwestern parts of the province. On January 5, the pro-China National Awami Party held a large meeting at the Paltan Maidan to celebrate Maulana Bhasani's return from China, but none of the speakers mentioned the riots that by then had affected more areas in Khulna and Jessore.

He found such behavior of the leaders of the struggle for democracy "deeply saddening." He knew his criticism would be unpopular and not sit comfortably with the leaders and activists the criticism was directed to. But he minced no words, "many of our leftist leaders and activists, too, are not fully aware of the danger of communalism. They fight against imperialism for democracy and socialism, but regarding communalism, their attitude, to a great extent, is like an ostrich.

If the democratic movement is strengthened, and people's struggle intensified, communalism will disappear automatically - such an obscure belief they maintain. This is an oversimplification of the real problem; denial of historical trends." In the communal hatred-charged atmosphere of today's South Asia, his observations are more relevant now than ever before.

Growing up in the post-Khilafat non-cooperation era, in a time that saw what he called the "transformation of difference and distance into bitter communal conflicts," he was fully aware of the danger of communalism. On the other hand, due to his familiarity with Pakistani politics, he knew how the ruling class of Pakistan whipped up communal issues and used them to derail any legitimate and democratic demand of the people, especially in East Pakistan.

In fact, he acknowledged that riots and communal conflicts were the main weapons used by the Pakistani rulers to enable their undemocratic rule. In communal riots in East Pakistan, Urdu-speaking Mohajirs played prominent roles, and it was known that the government instigated and used them. Zahur Hossain knew this very well, but he did not want to put all the blame on the people known as Biharis. He asked the uncomfortable question: if communalism was not well-entrenched in society, how was it possible for a small number of Mohajirs to carry out riots over and over again?

Tragedy and catastrophe (both natural and man-made) in the society he lived in were recurrent themes of contemplation for Zahur Hossain Chowdhry. He lived through the tumultuous events of the long twentieth century under three different states- British India, Pakistan, and finally Bangladesh - and he saw it all: wars, famines, riots, political assassinations, and natural calamities like the cyclone of 1970.

He saw men's humanity, and cruelty condensed in these events. It seems, the great Bengal famine and the great Calcutta killings in the 1940s, left an indelible mark on his psyche and shaped his worldview to a great extent. That's why we see his writings here and there strewn with incidents of his stumbling on dead bodies on Kolkata's Wellesley Street on the night of the blackout.

In his famous Darbar-e-Zahur columns, written towards the end of his life, we find a Manto-esque description of the Great Bengal Famine lurking "after eating a double-aanda jelly toast full up, holding a notebook with two fingers, at the gate of Calcutta University I saw a cadaverous man gasping to death like a fish drawn out of water", or about the notorious Great Calcutta Killing, "the sound of shattering human skull with a full-brick that I heard from two forearms away still rouses me from sleep." Such descriptions come as caesuras in his humorous and engaging prose and create an immense impact on the reader.

One of Zahur Hossain's persistent obsessions was exposing the Bengali middle class - the Bengali Muslim middle class in particular. An otherwise ever self-deprecating, Zahur Hossain Chowdhury confidently claimed to have spent much ink and paper over the years writing the biography of this class, to which he himself belonged.

Anyone familiar with his writings would agree that his skill in exposing the Bengali middle class - the Bengali Muslim middle class in particular - straddles between that of a sociologist and an artist. The recurrence of famine, riots, political intrigues, and assassinations in his writings had much to do with his explorations into the psyche of the Bengali Muslim middle class.

He identified this class as one "recently emerged from the paddy field, who made fortunes through permit business and black-marketing". More than anything else the mentality of this class was characterized by a strong longing for easy access to wealth and power - and these two reinforced each other.

He saw the profiteering mentality among businessmen, bureaucrats, and politicians during the Great Bengal Famine in British India; similarly, in the Pakistan era; and again, after independence, in their scrambling for power, hoarding, and black marketing during the famine of 1974, and in their acquisition of state-owned industries after 1975.

According to him, rather than going through the hard way of competition, the Bengali Muslim middle class always preferred the easy way of acquiring the favor of state power to perpetuate their life of comfort and privilege.

Behind the return of authoritarian rule, corruption, and assassination in Bangladesh in renewed intensity, even after the bloodbath of 1971, he identified the profiteering mentality and greed of the Bengali Muslim middle class. He sarcastically described the reality in the aftermath of 1971 as our version of "one step forward two steps back." He was frustrated and angry over the state of our society and culture, but did not wrap himself in cynicism, nor did he develop any bitterness. He kept doing what he did best - telling truth and exposing lies and criticizing the power. His writings in the Bangladesh period of his career are no less sharpened than anytime before. Looking at the prevailing condition in Bangladesh, his writings seem to be more important now than in his lifetime - they show us what it is that still ails our society.

Mohammad Afzalur Rahman is currently pursuing his PhD at Jawaharlal Nehru University. He can be contacted at [email protected]

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments