Foreign literature is a very precious tool for peace

Daily Star Books' panel on January 8, Day 4 of the Dhaka Lit Fest sought to take the audience to a more existential aspect of what the festival attempts to do. Who chooses which stories deserve to become books? Who chooses whether news of those books will even reach readers? Does book criticism truly help the flow and business of literature within and across national borders?

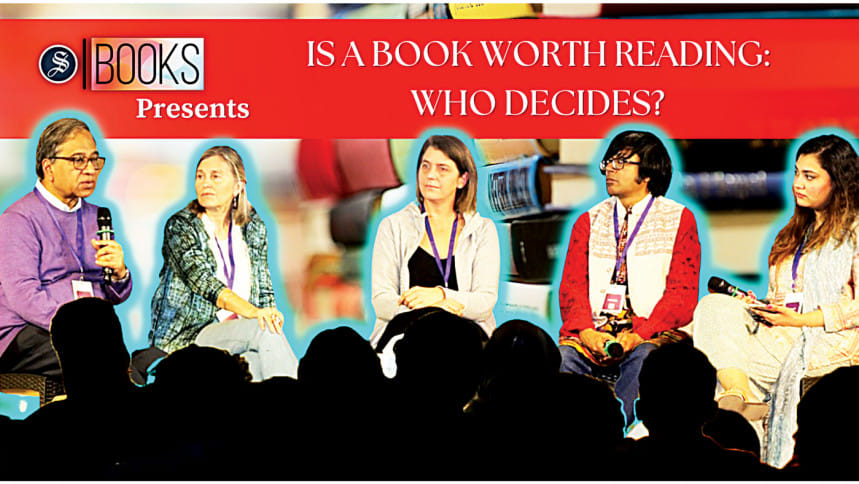

Moderated by DS Books Editor, Sarah Anjum Bari, the panel included writer, editor, translator, critic, and academic Fakrul Alam; French author, journalist and literary critic Florence Noiville; researcher and academic Mashrur Shahid Hossain; and Annette Köhn, a Berlin-based graphic designer, illustrator and publisher of young and emerging artists.

What are some of the factors that come up when we're deciding the 'worth' of a book?

Fakrul Alam: With a good review, you can tell that a book has stirred a reader's imagination. There are two kinds of book reviews in Bangladesh—one that, like a magic carpet, takes you somewhere else, and the other is when somebody you know has written a book and they dump it on you. I can say no to some, but it's something that you have to do.

Annette Köhn: For me the worth of a book is that it has to be touching—you learn about a part of the author that is inside the story. The second is that it helps you learn something about a topic.

Mashrur Shahid Hossain: The very nature of the book defines whether it is worth reading and reviewing. I would like to differentiate between book reviews that appear right after a book is published—its major objective is to engage and inform the reader to read it or not read it, and literary criticism—which has more methodical rigour. The point is whether the book brings to the fore something new and something relatively less explored. As Annette pointed out, whether it is well presented is also important in order to make the book engaging for a reader.

Florence, as editor of foreign fiction for Le Monde, you're trying to bring the vast world of literature to your local readership. Fakrul Sir, you were also Literary Editor of The Daily Star. How do you curate your content?

Florence Noiville: The readership is there, and it is not the same readership as for The Guardian or the TLS. Except that I do not know exactly who they are. I make suggestions and the editor-in-chief has the final cut. But what I'm really trying to do is to not favour too much of the Anglophone world, meaning the white, classical English and American. We tend to be overwhelmed by translations. What is important is to bring, as you said, the entire world in those pages. In the long run, foreign literature is also a very precious tool for peace. It helps you get under the skin of the other.

Fakrul Alam: For me, sometimes it depended on what books were submitted to us. So sometimes it was a book that I thought would be good for The Daily Star readership. Occasionally we would experiment with a book—such as a poetry book written in Bangla.

I think book reviews should also be about going back to classics and reacquainting it with audiences.

Florence Noiville: I completely agree. If Tagore were republished by Galimard, that is something I would want to highlight. Forgetfulness is very common among us all and it's important to make links between authors of now and the past.

I also pay attention to small presses—they are the ones who make the discoveries and take all the risks.

Media coverage is not the only way we find out about books. First, we study them in classrooms. How much are we able to innovate our school and university syllabi in order to nurture readers?

Mashrur Shahid Hossain: How many of our hundreds of national and international authors are covered in our textbooks? We choose a certain number of authors and we consider them representative of a language or a culture. The very first choice of what to read is made by curriculum makers. The question to ask here is whether these curriculum makers incorporate literary critics. It is the critic who helps to develop or generate a literary and cultural tradition of a country. Which author we will use to be proud of our country, which author we will learn from about other countries, that is somehow defined and conditioned by the choice of writers and texts that we cover in our syllabi.

We have noticed some problems in the recent reconfiguration of our syllabi regarding writers from which language, religion, or ethnicity will be included or excluded. When a particular ethnicity or religion is represented in a curriculum, that gives us the idea that they do not exist. For instance, how many non-Bangla writers do we accommodate in our conception of Bangladeshi literature?

My point is that let us not fake objectivity. If I have a stance, let me make it clear that I have a stance so the reader can decide how they will perceive my choices.

Fakrul Alam: I have more experience selecting texts for Honours and Masters curricula in Bangladeshi universities. So how did I choose? It was based partly on my reading but also on the fact that I was privileged enough to travel abroad and get books that you wouldn't get here. So over the years of shaping the English department syllabus, I think I have contributed my bit to keeping us occura—with books from recent decades. The best thing to do is international networking. Going back and forth.

How much freedom do university lecturers and even students have in selecting what to read in classrooms?

Fakrul Alam: We have a top-heavy system. I would say that the selection is more nuanced now than before. We have African literature, we have Latin American literature—previously it was only English literature. Cultural studies has also contributed to this widening of the syllabus.

As for students, they can choose if only they read a lot. I just took a national university class for college teachers, and all of them were complaining that no students read. I told them, did you ever ask yourself if you taught them how to read? So I'm not blaming the students at all.

Read the rest of this conversation on The Daily Star website and on Daily Star Books' Facebook, Instagram and Twitter.

Sarah Anjum Bari is editor of Daily Star Books. Reach her at [email protected] and @wordsinteal on Instagram and Twitter.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments