Into the rhyme and reason of poetry

I think I've always been a poet. Even when I thought as a teenager that I would grow up to be a best-selling novelist, I sought out layers to peel off my phrasing; I sought out words that travel beyond their scope and I had a habit of writing and rewriting my sentences until they felt like a fluid ripple gracefully dripping off my tongue as I read them aloud. But I'm going to make a bold claim here—I think we all are poets. To be human is to be a poet. And I will tell you why.

Anyone slightly versed in the literary world will tell you how poetry happens to be the most ancient form of literature. How so?

You can easily infer from the cave paintings of prehistoric human species that our history and prehistory relies on narratives. Think about it: the written records of tales as ancient as the Iliad, Odyssey, Vedas, Mahabharata, Ramayana all came in verse form. Hellenistic dramas were written in verse and remained a tradition carried forward for centuries in theater up until the finessing of the Elizabethan dramatists. The teachings of religious scriptures remain encased in the opulence of verse.

For a long time, verse remained the marker of nobility. You had to uphold a certain rank in society for you to be worthy of it. As we can see in Shakespeare's plays, dialogues in verse, with especially intricate phrasing, are reserved for characters of high stature—either in society, or in morality. The verse of religious scriptures was gatekept by Christian religious leaders during the Dark Ages—the common man deemed unworthy of interpreting such depth of knowledge hidden within words. It is a practice still upheld in some Muslim societies, where some maulanas are seen to impart a biased interpretation of the holy word to the common man attending his khutba, while parents pressurize their tiny, blossoming Muslims to read the verses in their intended musicality and not knowing the intended meaning.

But is that the purpose of poetry? To be intentionally elusive? To be so elitist that it shuns away entire groups of people on the basis of their educational achievements or the lack thereof? I say no. Poetry is human.

Poetry is for all humans—regardless of which walk of life they come from. Poetry is imparted upon the toddler just beginning to learn to express themselves with half-formed sounds of their language—starting with the timeless verses of a black sheep or a twinkling star or a chaand mama. The greeting card industry, whatever's left of it, continues to rely on half-heartedly formed rhymes. Jingles on TV commercials, much more well thought out, follow the same formula: relying on the language of poetry to make their message memorable (even as I write this my brain is playing 'eita ki 16255?' on loop). Even the beggar trying to wear you down into sharing alms employs requests spoken with a rhyme and rhythm. Why then do so many people disregard poetry with the claim that they don't understand it?

All I can interpret from this is that poetry is widely misunderstood. Is it that we don't know what poetry means? Do I need to define poetry? Probably not, but for the sake of my prose, I will. The most immediate definition that any literary-inclined individual will probably think of is Wordsworth's—"spontaneous overflow of emotions." If I truly examine my own experience as a poet, my first poem, which I still have documented, was indeed just that. I felt so much and I did not have space within me to contain those feelings, so I let them overflow, pouring down as acidic words drenching the page of my diary. But I wanted to see if my contemporaries thought if there was more to poetry. And of course they did.

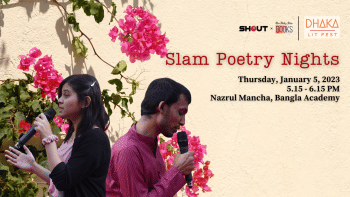

Stewie Chatterjee, with whom I have come to know from sharing the stage of DS Books & Shout's Slam Poetry Nights, says "the poetic exercise, in [its] essence, is simply saying something" with intent.

Raian Abedin, a writer whose Instagram poetry I had been following for a long time, says "poetry has been the most important way I've navigated the mess of my life, and it really didn't start until I began to explore both language and myself in ways to understand what I truly wanted."

Another writer, Uzayer Masud, says "poetry is where we start to push the bounds of language to describe things that we don't have words for. For example, consider how you might describe the colour red to someone who has never seen it before. There are no words in [any] language that can describe red for what it is."

Through all of our experiences, I find a singular motif: poetry is expressive. For me, it is an expression of feelings; for Stewie it is an expression of their beliefs; for Raian, it is an expression of his unconscious identity; for Uzayer it is a medium for defining the undefinable. How can poetry be elusive then?

Yes, poetry is an expression of the poet in their own language–in the words they feel comfortable wearing as their identity. But it is malleable. Eliot can write his gaudy verse if he wants to but Kaur too can write her simplistic expression because she wants to. With every form of art, there are standards that define their prestige–but just as fast-fashion is still fashion even if it is not couture, and a toddler's crooked illustration of a butterfly that resembles a mouse more is still art even if it is not Van Gogh–what you write or say to express a feeling or thought you simply can't contain is poetry, even if it is not embellished with the poetic devices studied in Literature classrooms.

Because, as my brilliant O Level English Language student, Ms. Areeba Parvez, points out–poetry is a feeling. When you listen to Vivaldi or the tracks that the Lo-Fi girl studies to, you don't need words to make sense of the music. It is simply a feeling some part of your brain instantly connects to, and you interpret what this music means to you. Just as my perceptive O Level Literature students, Ms. Nashra Jamal and Ms. Samiha Tahsin, point out–you can just give poetry your own meaning!

Ultimately, this is what poetry offers to generations now and generations of the future: a tool for expression; a tool for overcoming the limitations of language.

Moreover, if language is one of the most distinctive attributes of humanity that sets it apart from prehistoric homo sapiens with their 'confused unga bunga', then surely, poetry is the epitome of being human.

Just as one of my favourite poets on Instagram and a regular reader of Star Literature whose writing often graces its pages says, "[poetry] attempts to delve into the pure essence of who we [humans] are, the why's and how's that facts and data fail to reach."

As the rest of the human world tumbles forward in their race to emulate itself and the mind behind it through AI, machine learning, metaverse, etc., poetry is already human–as human as it gets–as it sits back, watches human idiosyncrasies and details them for the future generations to know how far we've advanced and feel how little we've changed.

Tashfia Ahmed teaches O Level English Language and Literature at Scholastica and ghosts followers of her poetry on Instagram. She requests that you leave her tasteful hate comments at her handle, @tashfiarchy.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments