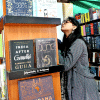

A bookstore is a time machine—Zeenat Book Supply through the ages

Books are rooms. Books are spaces. Their stories may inhabit us, but we inhabit them just as much—from the gate of the front cover to the markings etched across its pages and the smells that seep into its soil. Each smudge, each stroke of ink is a landmark that transports you to a corresponding past. Much like walking down the street of your childhood home.

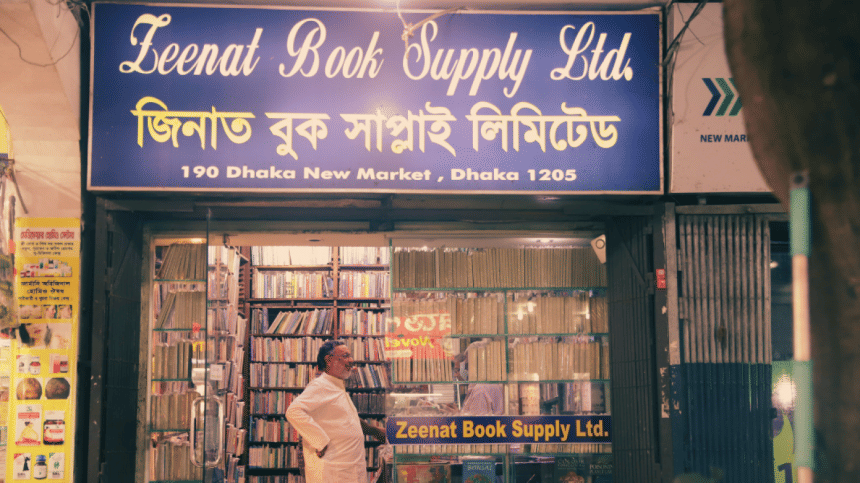

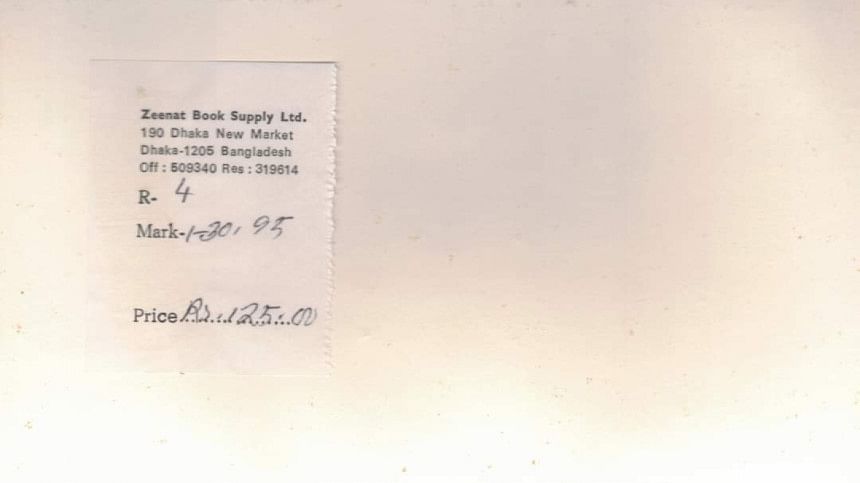

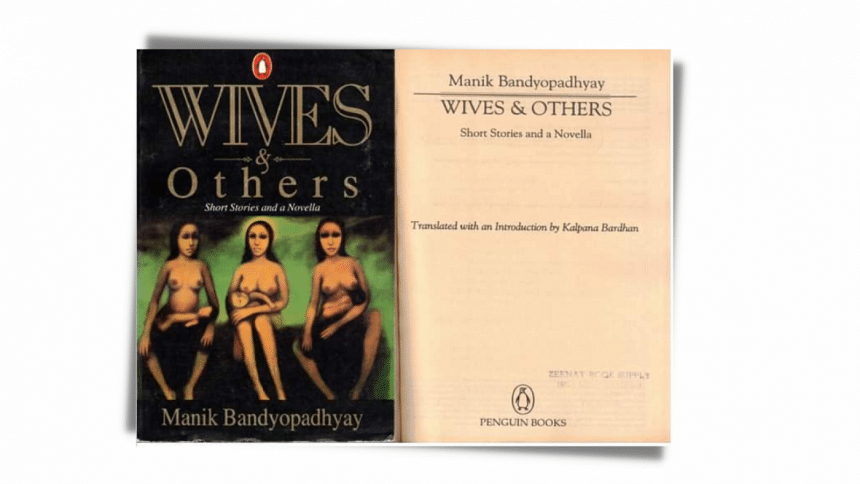

To most people who lived in or passed through Dhaka, particularly through the '60s and '80s, the cracking open of a weather-beaten spine may uncover a small, purple seal stamped onto the bottom right corner of the book's front pages. 'Zeenat Book Supply Ltd. 190 Dhaka New Market Dhaka 1205 Tel 509340'.

A soft laughter. "Ashole amader dokaner lokra onek puraton manush toh, our staff have been working here for so long that they are partial to these old practices instead of the more cost-effective stickers I keep getting for our books."

And so the memories come leaping back.

'I think it was at Zeenat I first said, 'Wow, this Stephen King guy seems very popular."'

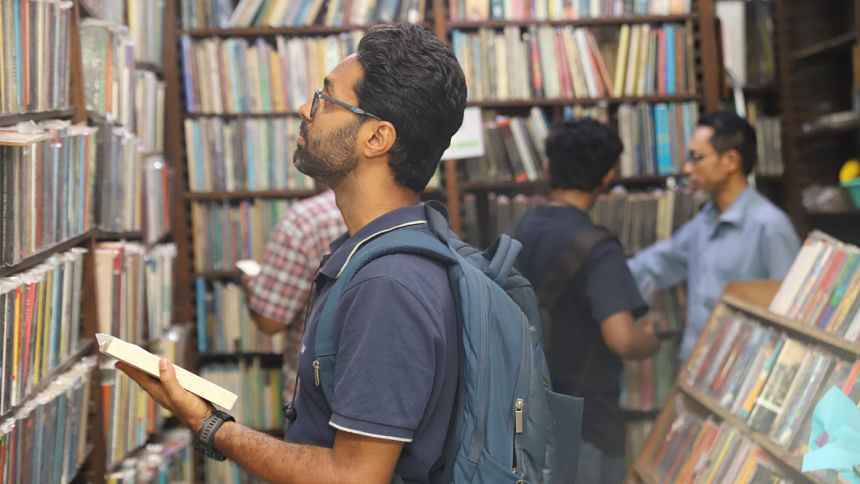

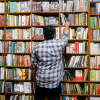

This past week, while hunting for readers' most meaningful memories at one of Dhaka's oldest bookshops in New Market, I expected to chance upon something like a Quality Streets box of chocolates, varieties and all. But stories command their own trajectories, and the memories I gained access to are, across a spectrum of ages and backgrounds, all the same.

"My mom used to buy books from there whenever she took us to New Market", says music journalist Milu Aman, who has recently authored books on Bangladeshi rock music and the late music composer Niloy Das.

Dr. Faustina Pereira, a human rights lawyer and academic, treasured the monthly trips to New Market with her mother in the 1970s. "As a young girl, I would save paisa by paisa, my precious allowance money from weekly chores", she says.

Aspiring writer Sameirah Nasrin Ahsan is to be found alongside her toddler at most children's storytelling sessions in the city's bookstores these days. She says, "Zeenat was one of the few places we frequented, I vaguely remember going through books there with my mom close by, there was a table fan there somewhere. I remember the sound of its gentle hum, the periodic rustling of paper as the fan slowly oscillated from side to side. After we picked our books, I remember reading them on our way back home, stretched out on my mother's lap, my senses filled with the sweet fragrance of new books and Maa's starched cotton sari."

Whatever concerns I felt at the similarities of these quotes soon shed away to make room for awe.

Please don't tell our mother!

A bookstore is a unique site of community building, one of the few places where a child can feel their tastes are as important, as worthy of commanding physical space as an adult's, while a grownup can revel in the whimsy that children enjoy from listening to stories. Bookstores make space for diversity—of interests, of backgrounds—and also for dialogues manifested by time travel. That all those anecdotes surrounding Zeenat are nearly identical speaks volumes about the kind of space it created for its clients. They testify to a nuanced, very tender portrait of Dhaka life, spanning back years and decades, of both mothers and fathers nurturing their children's intellectual curiosity, their emotional development and, therefore, their agency.

"Our school awarded high achievers with book vouchers from Zeenat. I remember feeling really important going to Zeenat to 'cast in' my award. For years after that, my association with the bookstore was as a reward for hard work", says writer , editor, and Sehri Tales founder Sabrina Fatma Ahmad.

Perhaps most precious in these accounts is the proof that so many different people can harbour such similar, overlapping memories and sentiments, despite all that may separate them across age, class, interests and experiences. In this last respect, the culture at Zeenat seemed to bleed into a community role all but absent in Dhaka—that of the library, which wipes out the capitalistic undertones of a bookstore's operations.

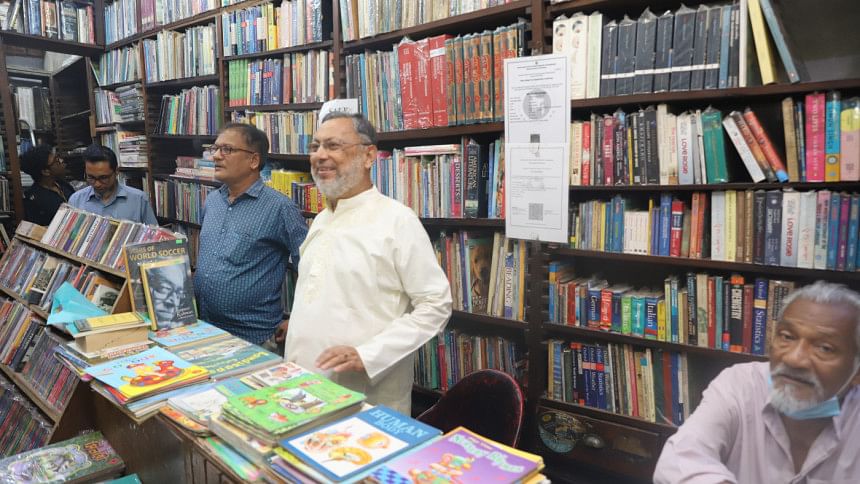

This is what occurs to me when I spend an hour and a half on the phone on Monday night, listening to and laughing over the episodes in the history of Zeenat Book Supply shared by store owner Syeed Mohammad Faisal, who has been its life force for 47 years.

"Two young brothers—they are all grown up and quite well known now—they would sneak out of their home when their mother took her afternoon nap", he recalls.

"They would run to Zeenat, pick up books from the floor and read as much as they could while sweating profusely in the heat. They scrambled back home before they could get into trouble, their sandals flying. Please don't tell our mother, they would say."

"Other times, every single day, I would catch one or two thieves who came in to steal our books because they didn't have the money to buy them. We caught them, let them go, caught them again a few days later. They came back again and again not to resell the books but to quench their addiction to reading. Shei boi porar nesha."

School of reading

An outpouring of news and social media posts have revisited Zeenat's origin story since Syeed Faisal announced that the shop will be closing on May 1, 2023. Syed Abdul Malek, a government employee in East Pakistan's Public Works Department, opened Zeenat to fill up his time after his office hours ended by 2 PM. Entertainment options besides the newspaper and radio were limited. This was in 1963.

In 1974, a young and Notre Dame-graduated Faisal would feel the need to take over the store as his father neared retirement, and members of the staff started handling the business unethically. Taking care of the business would ensure a better life for Faisal's siblings—a brother and sister—the latter the namesake behind the store. By 1993, when its founder passed away, Zeenat's running was entirely in Faisal's hands.

"It would be nice if you could send me the link to the article when it is published", he tells me when we discuss this story. "My sister Zeenat lives abroad, and she keeps saying she wants to read what people are saying about this bookshop named after her."

His early days at the shop would start at 9 AM in the morning, running past 10 at night. A tiffin carrier bearing lunch went with him on his commute—a bus ride that cost him 4 ana around the Nilkhet bend. Any 1 or 2 anas remaining in his pocket would reward him with a rickshaw ride at the end of the day. "The roads used to be empty. I sang aloud when I rode the rickshaw at night", Faisal recalls.

Other times he would walk, to better his health and reserve the energy to talk to people at the bookstore all day long. Bringing up these conversations softens his voice, makes him even more animated, as he remembers customers who have passed away, though their children and grandchildren now visit Zeenat to retrace the steps of their long gone family members.

"The bookstore witnessed the evolution of my life journey through my changing tastes in reading material, including my years as a law student in the early '90s and then as a lawyer. I am certain I am only one of many who can recount similar 'coming of age' associations with this iconic store", Dr. Faustina Pereira says.

Other authors, activists, artists, and readers echo the sentiment—at Zeenat Dr. Pereira discovered Archie Comics, DC and Marvel comics, Nancy Drew and The Famous Five; Arif Anwar, Toronto-based author of The Storm, discovered Stephen King; Nodi Tabassum, a lecturer at Southeast University, discovered discounted leather-bound editions of Wordsworth, Scott Fitzgerald, Virginia Woolf and The Little Prince. Milu Aman was asked to read Ulysses by Syeed Faisal himself. "It was the passion and encouragement that he showed to me when he said those things that really moved me", Aman recounts. "I remember he said, it's one of the greatest literary pieces ever written, you get to know everything about life and the meaning of existence."

In a 2014 series of articles on the decline of South Asian translations, writer and translator Mahmud Rahman recalled how a journey to Dhaka from his home in the United States always includes a trip to Zeenat, one of the few places in Bangladesh that carried English texts in translation, books covered in dust or dirt-brown edges, others wrapped in plastic. Shrilal Shukla's Raag Darbari, Bama's memoir of a Dalit Christian experience in Karakku, Anand's Desert Shadhows. Translations from Hindi, Tamil, Malayalam.

This sense for which books would work for his audience and which wouldn't is an art that Faisal had to master on his own. It involved reading and listening. Circa 1975, Zeenat sold Bangla course books and textbooks for board exams. It was in '77 when they started importing from abroad, around the same time that English medium schools such as Dhanmondi Tutorial, Green Herald, Southbreeze and Sunbeams started flourishing.

"I held book clubs with 20-25 students of the O/A Level classes", Faisal says. "I would give them two books and have them discuss their reading experiences."

In addition, he devoted hours and hours to reading book blurbs, prefaces, and summaries sent over in print form by publishers from abroad—texts on science, philosophy, architecture, literature.

A bygone era?

The passing of years helped Zeenat swell into a grandfatherly figure of sorts among Dhaka's reading community (though he doesn't describe it that way himself). If in one breath Faisal recalls Professor Abdur Razzak spending hours by the bookshelves, a shy, timid smile constantly playing on his face, in another the bookseller speaks of sharing stocks of books with fledgling enterprises that would go on to garner their own big reputations, such as Sunbeams, Scholastica, its bookstore Etcetera. In a past interview with The Daily Star, Sabrina Shefa spoke of how she learned the ropes of running a bookstore from hours of sitting inside Zeenat, talking to Syeed Faisal and observing their operations. The experience helped her to launch Charcha, once a favourite among book-lovers in Mohammadpur.

The beginning of the end began when photocopies and then locally printed copies began infiltrating the market. The drastically lower prices of these "local copies" would prove tough competition for original, imported books sold at stores like Zeenat, who have to bear with steep import taxes on top of exchange rates. The presence of foreign publishers operating from within the local market would be the most viable solution to these price wars. But, in Faisal's experience, the sheer magnitude of piracy in Bangladesh discourages publishers from wanting to operate here.

The arrival of digital alternatives—not only in book buying habits but also in entertainment mediums—has dragged readers farther away from devoting time and money to brick and mortar stores selling original copies, Faisal believes. For shops like Zeenat that don't have alternate revenue streams or a young, digitally savvy staff to compete with online practices, survival can be all but impossible.

But readers both agree and disagree.

"I think reading is antithetical to our consumption of digital content. The latter is defined by its quickness, its agility in production, whereas reading demands an alertness that's difficult to exercise when the other media options are so enticing", says Minhaz Muhammad, an Economics graduate of North South University who also curated and sold books at Mohammadpur's Charcha.

He adds, "I've seen folks talking about how much they enjoyed going to the store when they were young and I found it funny—why did they stop going there once they grew up? They folks have experienced tremendous upward mobility. From Dhanmondi, New Market, Shahbag, they have moved to Gulshan, Banani. Their bookish needs are met through their bi-annual foreign trips."

While many readers have posted online about Zeenat's closing down due to an unwillingness to adapt to online selling, Minhaz believes that what sets Zeenat apart is its lack of glamour amidst other bookstores competing to offer a photogenic interior for social media posts.

"The people who went to Zeenat went there to buy books, nothing else. It's a rare feature here—Zeenat remained the same as it was when it was founded. There is a dignity in its quietly closing down, in ending things on one's own terms", he says.

Finally, some time to read

Md Shafiqul Islam, a poet and Professor of English at Shahjalal University of Science and Technology, Sylhet, believes that "the concerned authority, including the Ministry of Cultural Affairs, may come forward to support so that the culture of reading continues to progress".

Dr. Faustina Pereira agrees that "the government can step in to protect authors, publishers and sellers through appropriate legal and policy support. Authors' and publishers' guilds can be strengthened, just as anti-piracy provisions can be legislated and implemented vigorously."

But the owner of Zeenat Bookstore believes that their decades-old staff will struggle to adapt to the ways of online selling, and he himself would have been able to run the bookshop for 5-7 more years at the longest. Each of his two daughters are alternately living abroad and succeeding in a career in banking.

It is after an hour and a half of discussing the history, the technicalities, and the pitfalls of bookselling that Syeed Faisal finally tells me about his own reading tastes, and what awaits Zeenat's books after the end of its last month.

Faisal enjoys reading nonfiction books on the history of knowledge and Russian classics. He is fascinated by the circumstances in which iconic stories are written, and he's looking for any such texts that contextualise the writing of Rabindranath Tagore's poetry. He enjoys gardening.

After Zeenat Book Supply closes its doors on May 1, 2023 after a sale as generous as its six-decade history, Syeed Faisal plans on selling each remaining book, one at a time, at discounted rates from his social media. Having spent upwards of four decades reading thousands of book blurbs and synopses, he now plans on reading more of the texts inside.

Sarah Anjum Bari is the Books and Literary Editor at The Daily Star. Reach her at [email protected] and @wordsinteal on Instagram and Twitter.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments