Kyrgyzstan: A tale of an eagle and a bond

The eagle man was waving at us; he wanted to tell us something. Our Kyrgyz driver was eager to start the 200 kilometres return journey to Bishkek after a day-long trip. However, we stopped to listen to what he had to say, and what we got remained the highlight of the tour.

Sarmin and I have been travelling around the world for the last 15 years. For the two of us, it has become the way of life, perhaps a path to happiness as a couple.

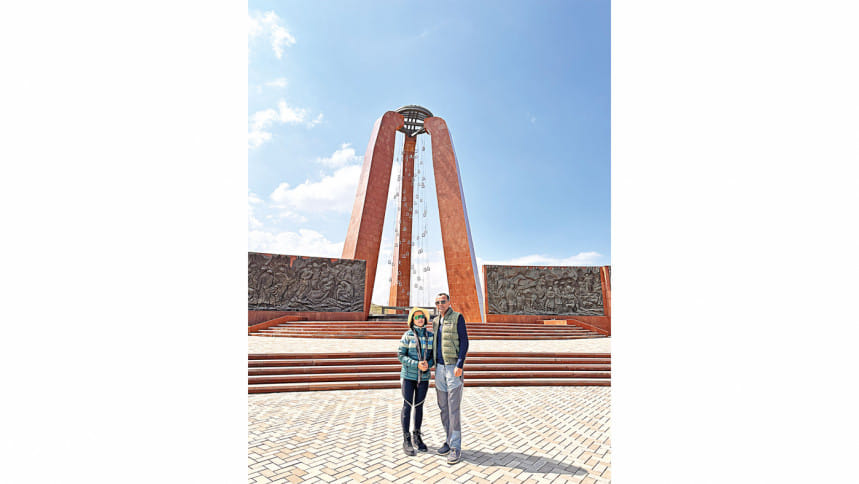

While we had visited Central Asia before, this marked our first time in Kyrgyzstan. Arriving from Uzbekistan in late March, we found ourselves in this landlocked nation bordered by Kazakhstan to the north, Uzbekistan to the west, Tajikistan to the south, and China to the east. Like its neighbouring countries, Kyrgyzstan gained independence following the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991.

The majority of its lower-middle-class populace resides near urban areas, yet a brave few choose to inhabit the vast mountain ranges that encompass over 90 percent of the country's territory.

The allure of Central Asia's authentic lifestyle compelled me to return time and again. The world has changed dramatically; settlers with easy access to the seas have long since transformed the Americas, Europe, Australia, and much of Asia. Only a few places, like landlocked Central Asia and Africa, remain relatively untouched.

Before arriving in Bishkek, we meticulously planned our journey with a local driver and guide named Begaly. Together, we explored Uzbekistan's cities, national parks, lakes, monuments, and historical sites. However, one of the most incredible experiences we encountered was entirely unplanned.

Begaly informed us that he could arrange an eagle hunting show, and after hearing a few details, we agreed.

For over ten thousand years, humans have relied on animals to fulfil various needs. Our superior intelligence has allowed us to harness their speed, power, and unique abilities for our benefit.

Eagles, with their remarkable eyesight nearly eight times sharper than ours, have played a significant role in hunting. Capturing and training these majestic creatures is a centuries-old tradition in Central Asia. Nomadic people, who call the high valleys of Central Asia, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Mongolia, and western China their home, have preserved this eagle hunting tradition.

Today, this tradition is regulated by state and local governments.

Capturing and training a golden eagle is no easy feat. These magnificent birds maintain a home territory of approximately 200 square kilometres and prey upon rabbits, mountain goats, and even wolves. The process requires meticulous preparation and several years of training. The master must treat the eagle with respect and care, as any aggression or mistreatment could cause the eagle to flee, never to return.

The master communicates with the eagle through speaking, signing, and humming, imprinting their voice on the eagle's memory. During training and even afterwards, the eagle's eyes are covered with a head musk to maintain its calm and dependence.

We embarked on a 200 km journey southeast of Bishkek, arriving in the Issyk Kul region in the afternoon. The eagle man was scheduled to meet us near Lake Orto Rokoy.

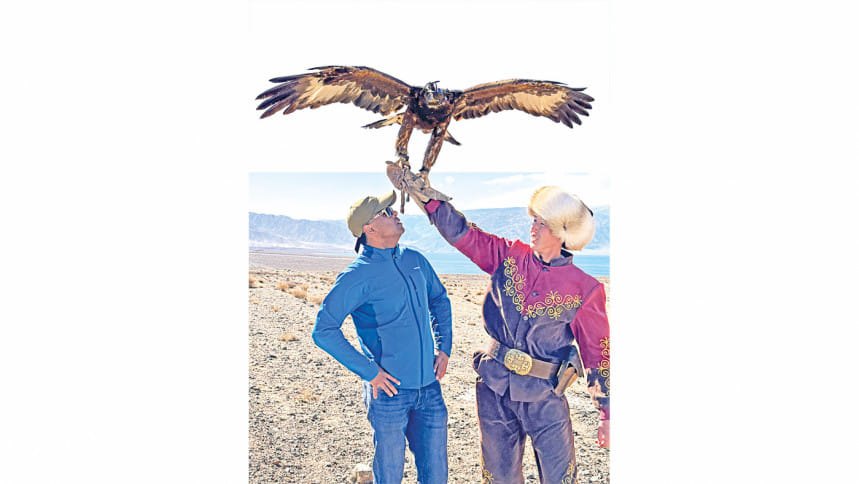

Around 4:00pm, he appeared, accompanied by his golden eagle. The eagle man had travelled 90 kilometres from his village to join us by the lake. His brothers accompanied him, along with a dog, a stuffed fox, and a domesticated rabbit.

It was a breathtaking day, with the sapphire lake reflecting an equally blue sky and surrounded by dry, grey mountain peaks.

Without delay, the eagle man led us further into the mountains. His brother carried the eagle about half a mile away from us and released it. With a whistle, the eagle soared. Its target was the rabbit released earlier by the eagle man.

In no time, the eagle captured its prey. This demonstration showcased the eagle's natural hunting prowess.

After the hunt, a trained eagle waits for its master to arrive on the scene. As the master gives a reward, usually a piece of meat, the eagle releases its hunt from its powerful claws, which have a grip strength of over 500 psi. That's strong enough to break any bones.

We captured countless photos and a few video clips, savouring the awe-inspiring moment. The time came for us to settle the previously agreed amount with the eagle man. As a gesture of appreciation, I added a little extra and instructed our driver to convey that it was intended for the eagle. The eagle turned out to be a three-year-old female with an expected lifespan of twenty-five years.

However, the eagle man would not keep her beyond ten to fifteen years. Releasing captive eagles into nature is a tradition. Before release, the master trains the eagle to survive in the wild. On the day of liberation, the master may even sacrifice a large animal in the mountains as a gift to their loyal companion.

On that day, we bore witness to the profound bond between the master and the eagle.

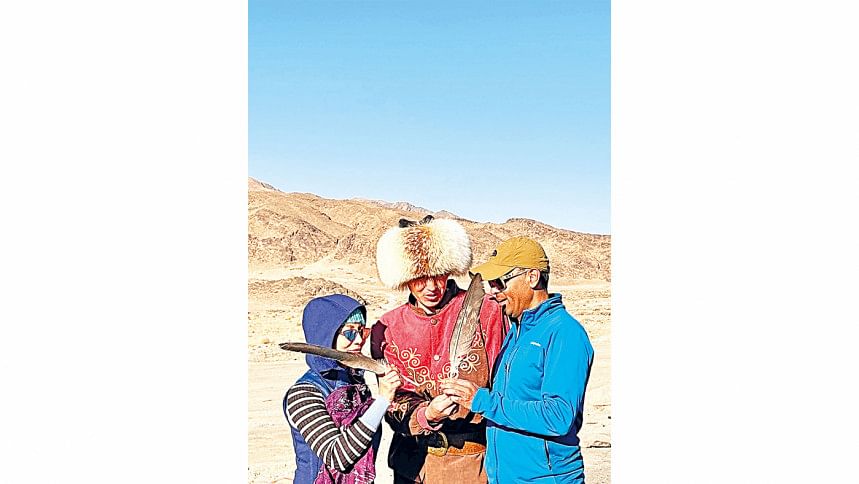

As we embarked on our return journey, an extraordinary occurrence transpired. As mentioned at the beginning, we paused. The eagle man approached us, offering two feathers from his golden eagle. It was a heartfelt token of his affection. Though we lacked a common language, we understood that a connection had been forged.

Now, whenever I glance at those feathers adorning my living room, they transport me back to that cherished time. They serve as a reminder of a man in a distant land, whom I may never see again, but whose memory shall forever endure.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments