As I Remember Syed Waliullah, My Papa

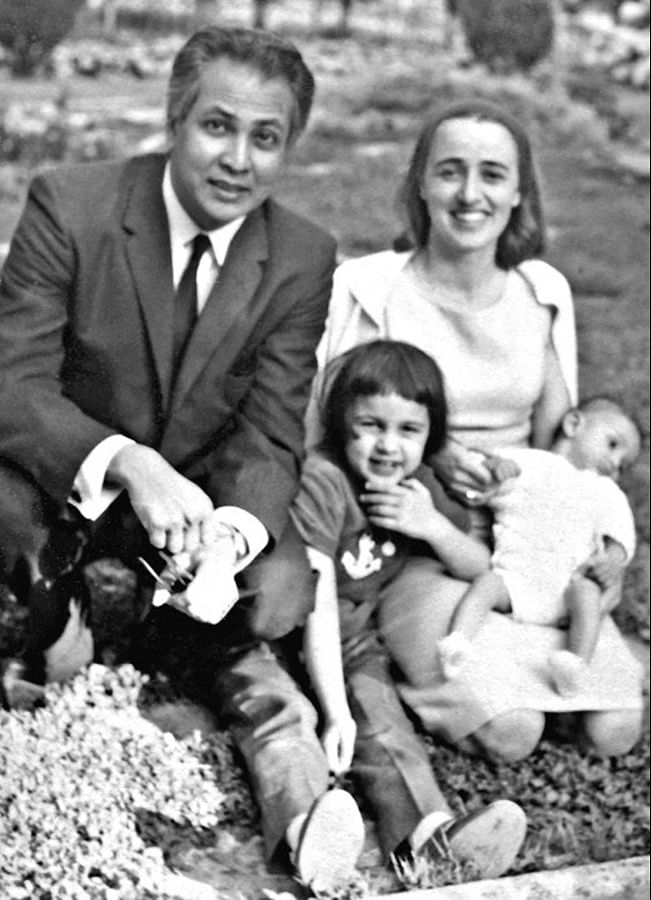

Thinking of Syed Waliullah and being his son always triggers contrasting feelings of joy and pride, melancholy and pain. Regrettably, neither my elder sister Simine nor I am able to remember much about our father, as we were both very young when he passed away. His loss was a terrible shock that severely impacted and changed our lives forever. While our mother was trying to balance her personal grief and raising us on her own, we had to live with the fact that we would no longer be able to develop and nurture the Bangladeshi half of our parents' heritage. However, I am pleased to share some intimate recollections and personal feelings about Syed Waliullah as a father, who is known to the many readers of Bengali literature as a writer.

I know many of these facts from my mother and some I remember myself. My mother regaled us with many stories about him, some of them that she even published in a book titled My Husband as I saw him ('Amar Swami Wali' by Anne-Marie Waliullah, translated by Shibabrata Barman and published in 1999 by Prothoma Prokashan)

One monochrome photograph of my father is still preciously kept on my bedroom shelf. It shows him wearing spectacles, a bow tie, and sitting on rattan furniture. My mother, seated beside him on the sofa, is wearing a close-fitting striped dress, Grace Kelly style. The sofa and the dress in the picture were designed by my father. Syed Waliullah was not only immersed in literature but was also a multi-talented man who used to paint, draw, and design.

My parents met in Australia where my mother was working at the French embassy. My father was there as Press Attaché in the Pakistan Embassy. They met at a party – the embassy officers typically dressed in white suits with an orchid on their lapel. Like the others at the embassy, he smoked Sobranies with the country's emblem printed on the cigarette paper. My parents married several years later in Islamabad – my mother converted to Islam, taking on the name Nasreen. Together they lived as civil servants in different countries in Asia and Europe. Lastly, when he was posted in France, he took a job at the UNESCO headquarters in Paris, where they finally settled.

They lived in an apartment in the 16th arrondissement of Paris, one of the nicer residential areas in the capital. There were very few Bengalis residing in France in the 1960s. Of course, our family socialized a lot with this small community. I will always remember the day when Papa took us to visit the famous Bangladeshi sculptor Novera Ahmed who lived in a charming little house in Paris. I was fascinated by her rather unusual pet: an owl freely hovering above our heads.

When Bengali people visited Paris, my father demonstrated a great sense of hospitality and tirelessly welcomed them and gave of his time as a tourist guide. Because of these many occasions, the Louvre as well as Versailles palace no longer held any secrets for him. Our home was a lively home often filled with guests. And luckily our parents would allow us to stay and participate in the entertainment in this world of adults. Among them, my father's dearest friends were Syed Najmuddin Hashim and the artist Rashid Chowdury, both of whom used to visit frequently. I also remember well Humayun Rashid Choudhury and his family; they were close and regular visitors. Truly, our father wouldn't miss a single occasion to spend what he considered to be special moments with other Bangladeshis. Homesick, he enjoyed recreating in our apartment the flavour of his beloved country, like Bengali food, long and intense discussions with friends, and musical performances.

My sister Simine remembers well how he enjoyed listening to music; his tastes included classical western music, jazz, Indian music, and, of course, he had a significant collection of records of songs by Tagore and Kazi Nazrul Islam. He would often sing himself with a very soft voice, and I can still sing by heart some of these songs of my youth: Noor Jahan Noor Jahan, for example. He also introduced his daughter to contemporary western music like Bob Dylan, the Beatles and the Rolling Stones and often went to concerts and shows, for example the hit musical comedy Hair.

My father's library consisted of a large and varied number of books reflecting his great intellectual curiosity; these included some of the best of world literature, history, social sciences, art, but also thrillers like those of Raymond Chandler.

I remember seeing him lying down on the sofa reading. And, like him, I too prefer a reclining posture when reading or even writing, a habit I must have inherited from him. I cannot recall when he had the time to write, except that he was very nocturnal. In fact, he would come home from work at UNESCO late every evening and rarely empty-handed since he brought us small gifts. Also, he would often spoil our mother, using any made-up pretext he could think of, just "to celebrate", as he used to say.

He was a very affectionate father and would take time to tell bedtime stories.Yet sometimes, he could also be a strict and disciplinarian father. I remember him always wearing a suit with a tie or a bow tie, very occidental in style. Sometimes he wore lungis, but only in private. He was formal and elegant in his appearance, and always paid extreme attention to his manners and presentation, both publicly and privately. He was very autonomous in his domestic affairs, including washing and ironing his own clothes. He loved cooking too, making appetising chapatis and delicious shami kebabs and he did not begrudge having to wash the dishes on various occasions.

My sister's recollections of my father are a little clearer than mine as she was older than I when he passed away. She remembers papa working on his book-covers, which he would design, draw and paint himself. She recalls about four or five final designs for the Chandar Amaboshay book cover – particularly a print-like composition with a full moon in black against a dark-green sky and waves in white below. A version of this design was finally chosen for the cover. He was a perfectionist in his creative and domestic life; as a result, we have very few paintings by him because he would discard works that he didn't like.

My father understood French perfectly but didn't speak it with his children – he addressed us instead in his lightly accented English. He would have liked us to know Bengali, but it was hard to teach us the language in France at that time. However, our education was of great importance to him. It was slightly upsetting for him not to be able to be closer to our educational experiences and he was very concerned with details of our dress, manners and etiquette at all times.

As if to emphasize our bicultural roots, we were deliberately given mixed names from ancient Persia and France. My sister and myself too gave Franco-Persian names to our children, Tristan-Timour and Shahane-Louise, except one, Margot-Swati.

My father was an amateur photographer. He usually carried his Nikon camera around his neck, and he was very fond of technology. He would take pictures of anything of interest that would appear before his eyes. We still have all the family photo albums. In view of the celebration of his centennial birth, my sister Simine edited a coffee table book titled My husband as I saw him, (My husband as I saw him by Anne-Marie Waliullah, edited by Simine and Iraj Waliullah and published by Nymphea Publication in 2022) which we intend to share widely. It contains a large number of unknown and intimate images of his life

We made several trips with my father – he was always eager to show us cultural sites and museums, including Louis Kahn's parliament building in Dhaka, which he was very fond of. My sister recalls several car journeys with him, sometimes with my mother's relatives – to Spain, Denmark and other places. He loved long-distance driving. These vacations were more cultural than anything else. He disliked going to the beach with us and if he did, he would wear a suit. He was not into sports and wouldn't dare to try to learn skiing with our mother, who was very good at the sport because she came from the French Alps region.

We also visited Pakistan and Bangladesh with him in the winter of 1969. There our mother wore saris and he wore suits during the days and evenings as they attended many formal events.

My sister recalls visiting a mosque in Dhaka with him – he was upset because she was not allowed to enter with him. His interest was mainly in showing her the architecture, not to pray, as he was secular and modern in his thinking. While he was interested in the cultural dimensions of Islam in Bengal, he was at the same time a strong critic of narrow-minded thinking, as illustrated in the novel Lalsalu.

Simine made a special trip with him to England in July 1971, ostensibly to introduce her to the museums and sights there, but in fact for the very special purpose of him getting more involved in the national struggle, pledging allegiance to the provisional government of Bangladesh and spending a great deal of time with expatriate Bangladeshis to discuss the war, the only major concern of his at that time.

Inevitably, his pattern of life changed when he was forced to leave UNESCO during which time the intense liberation struggle for Bangladesh had begun. I remember that he was devastated and deeply worried at the outbreak of the war, willing to return home through West Bengal and to contribute to the creation of Bangladesh. He helped as much as he could from France, mobilising French intellectuals for the cause of Bangladesh and generating public opinion in favour of his homeland during the last remaining weeks of his life.

The timing of my father's death coincided with the birth of a new country and a new nation. He desperately wanted to play a part in the construction of Bangladesh. He had purchased a property in Dhaka where he was planning to move permanently. In preparation for the move, I recall he sold his Citroen DS for a Fiat 128, which was the only kind of foreign vehicle that could be serviced in Bangladesh at that time. I remember its red export license plates, which, sadly, had to be replaced by regular ones after his demise.

My father was only 49 when he died in France. His grave is in Meudon, close to Paris, a simple structure that I often visit. Sometimes by chance, I come across with other visitors from Bangladesh. They honour my father for his contribution to Bengali literature, and I find this very moving and inspiring. For my part, I remember him as a man of his time, very westernized in his tastes and progressive thoughts, yet also deeply rooted in Bengali culture – and as a caring and loving father.

Other than these fleeting memories, my father remains somewhat of an enigma to me. Fortunately, the writings he left can be viewed as a testimony of his inner thoughts, perhaps the finest keys for understanding the man.

Syed Iraj Waliullah is the son of Syed Waliullah

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments