“Who Killed Mujib?” A Narrative with a Difference

'Who Killed Mujib?' is a recurring question that has haunted the nation since the unfolding of the tragic events in mid-August 1975. The brutal killing of the Founding Father of the Nation, along with his wife and children, may seem absurd to many members of the new generation, but more absurdity followed the tragedy itself. The killers were given protection under the Indemnity Ordinance proclaimed by the self-declared President Khondokar Mustaque Ahmed and later endorsed by an act of the Parliament led by General Ziaur Rahman. The killers not only physically eliminated Sheikh Mujib but also tried to erase his name from the pages of history. Falsehood won this first battle, but truth had to wage a long war to prevail. The killers were finally brought to justice, and the judgment was delivered on 19 November 2009. Even then, not all the accused could be produced in court as a few were absconding, finding safe haven in Pakistan, the USA, and Canada. With the case deposited in the court of law, one can say that the killers were identified, and justice was delivered. However, the question of who killed Mujib lingers on. It is well understood that the assassination of a head of state or government is always a well-orchestrated, well-designed plot where those who operate at the scene can be easily identified, but their powerful masters remain outside the purview of the public and the legal system.

A. L. Khatib's book 'Who Killed Mujib?' published in Delhi in 1981 was the first major work written with a combination of academic research and journalistic skill that calls for serious study. First of all, we have to address the question of who this A. L. Khatib is. Not many people know him these days, but he was a well-known and respected figure among the journalist community in Dhaka in the 1950s and 60s. He was an outsider who fell in love with East Bengal and its people. Many stories circulated around this exceptional person, whose full name was Abdul Latif Khatib. He hailed from Maharashtra, India, but his father went to the sea and settled in Colombo, Sri Lanka. A. L. Khatib started his journalistic career in Ceylon and then, via Karachi, came to Dhaka in the middle of the 1950s, working at the Observer and Morning News. He was a bachelor who stayed in the old press club building in a room with a few essentials but lots of books and periodicals. He was a close friend of Sanjeeb Dutta, son of the illustrious politician Shaheed Dhirendranath Dutta, and the poet-journalist Sayeed Atiqullah. Eminent Bengali poet Subhas Mukhopaddhaya knew him well and wrote: 'It never occurred to me to ask questions like where does Khatib hail from, who are the other members of his family, did he ever marry, is he a Hindu or Muslim, Christian or Buddhist. When he came to Delhi as the correspondent of the Bangladesh Observer, I became close to him again.'

A. L. was a keen observer of the political and social development of East Bengal since the mid-1950s, when the nation embarked on a great journey to confront the divisive communal philosophy of the Pakistani state and establish the right of the Bengali people to be masters of their land. He was a voracious reader with a wide interest and a sharp memory. In many ways, he reminds me of A.G. Noorani, Abdul Gaffar, with his AG, a confirmed bachelor who lives in his Mumbai apartment among piles of books and writes a fortnightly column in 'Frontline' full of historical facts and knowledge. Similarly, the book by A. L. has taken a deeper look at the tragic event and analyzed it from local and global perspectives. Of course, he portrayed the 'Killer Majors' and their cohorts, but he analyzed the event not simply as a conspiracy of a few but as a Joint Criminal Enterprise or JCE, a term that is very much in circulation now, especially in the International Criminal Court and similar other domestic tribunals established to try the perpetrators of genocidal crimes. Unfortunately, national criminal courts remain focused on individual criminality and, at most, address the question of complicity in the crime, but the larger plot remains outside their focus. That may be okay with the national legal system but is inadequate to answer the question 'Who Killed Mujib?

It is the duty of the nation now to try to address this pertinent question that is haunting the minds of millions. Research-based documented historical analysis is essential to gain a better understanding of the tragic killing of Bangabandhu. A. L. was a pioneer in this regard, a lone crusader who spent his life's wealth and experience to answer the question. On the one hand, he analyzed the global scenario, the historic emergence of Bangladesh, and the massive problems the devastated land faced in rebuilding the infrastructure as well as feeding the people. Thus, he contextualized the role and contribution of Sheikh Mujibur Rahman in the struggle of the nation and debunked many propagandist myths. He meticulously re-enacted the events of 15 August, the roles of the individual killers, while also examining their connections with a few close associates of Sheikh Mujib and tracing the communication they had with their higher-ups and foreign diplomats.

A. L. Khatib's portrayal of the 'Killer Majors' offers insights and a deep psychological understanding. He wrote: 'The 'I' is very pronounced in his (Farook's) utterances. 'I engineered the coup ---' 'I ordered Mujib's killing----'. 'I ordered Mujib's death'. Rashid is less enthusiastic in his utterances, but he too speaks only of himself. Neither Farook nor Rashid uses 'We,' though the two of them had plotted the killing of Mujib. Dalim proudly declared his name when he announced that the Mujib government had been toppled. Rashid thinks poorly of Huda, who failed to shoot Mujib. Huda ridicules Farook's claim that he gave orders while sitting on a tank.'

Such an analysis of the psyche of mass murderers reminds us of the analysis of the mind of Adolf Eichmann, the Nazi war criminal, conducted by the social thinker Hannah Arendt in her famous book 'Eichmann in Jerusalem.' She observed the trial in Jerusalem and wrote about the 'banality of evil' and the 'interdependence between thoughtlessness and evil.' Unfortunately, no social psychologist was present in our court when the killers of Mujib were put on trial, and there has been no political, social, or psychological analysis conducted about the extreme brutality of the killing of Sheikh Mujib and his family, followed by the murder of four national leaders inside the jail.

A. L. Khatib's portrayal of Khondoker Mustaque Ahmed showed his deep understanding of the politics of the Awami League and secular Bengali nationalism. He wrote: 'By the end of 1954, most members of the Awami Muslim League thought 'Muslim' in the party's name to be a hindrance and wanted it to be removed. But to Mustaque, the party was the 'Muslim League' with 'Awami' added to it. When more than 500 counselors voted at the Awami Muslim League council meeting in 1955 to drop 'Muslim' from the party's name, Abdus Salam Khan and Mustaque walked out of the meeting.' A. L. depicted in detail the whereabouts of Khondokar Mustaque Ahmed after the genocidal attack launched by the Pakistan Army. It took 13 days for Mustaque to decide to cross the border and join his colleagues in India. Mustaque was a reluctant participant in Muktijuddha, and A. L. analyzed the photo of the leaders of the newly formed government at Mujibnagar, where Khondoker Mustaque Ahmed was standing not in line but a step behind with less enthusiasm.

Mustaque was engaged in hatching conspiracy with American contacts in Calcutta to derail the liberation war, which also received high acclaim from Henry Kissinger, the National Security Advisor of the US President, a sinister character in toppling governments in many countries around the world. The Mustaque-Mahbubul Alam Chashi duo was the 'Calcutta-based Bangladesh leadership' for Henry Kissinger. About Kissinger, A. L. Khatib further wrote that the leaders whom Kissinger couldn't tolerate were Allende of Chile, Thieu of South Vietnam, and Mujib of Bangladesh. All of them embraced the same fate as expected by Henry Kissinger.

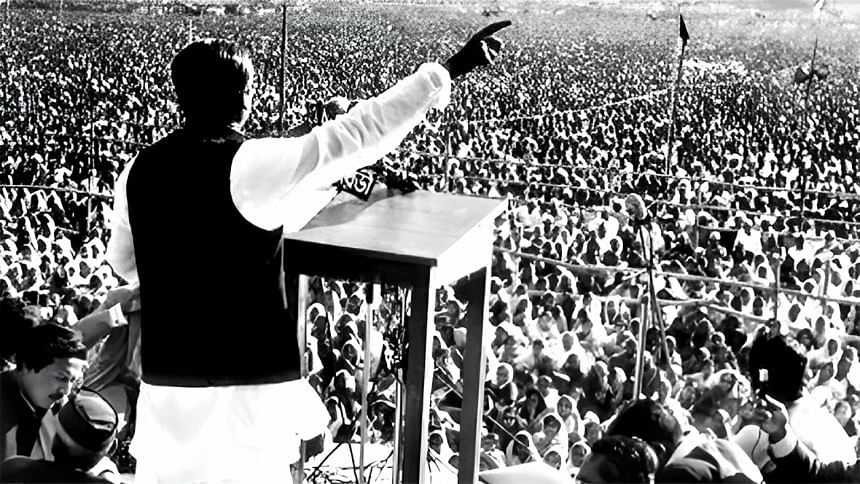

The main part of the book ended in 1977, and the manuscript went through the publishing process to be launched in 1981. Before the publication, A. L. Khatib added an epilogue describing Sheikh Hasina's return to Bangladesh in 1981. To Khatib, the reception at the airport was reminiscent of Mujib's triumphant return to Dhaka on 10 January 1972. His final words: 'Hasina, who had taken ill in Dhaka, was running a high temperature by the time she reached Tungipara on the afternoon of 19 May. She fainted as she was offering 'fateha' at her father's grave.'

A. L. Khatib's narrative ended abruptly, as his life came to an end in 1984 under dubious circumstances. The book became an instant bestseller, but surprisingly, publisher Narendra Kumar refrained from issuing any new print runs. The book just vanished from the racks of the bookshops. Strangely enough, the Bangladesh government of the time commissioned Anthony Mascarenhas to write and publish another book 'A Legacy of Blood' on the same theme to counter the book by A. L. Khatib.

But history moves on. Ultimately, truth has prevailed against falsehood, but the war is not over. We need a lot of work to be done in the light of A. L. Khatib's book to find a clear picture of 'Who Killed Mujib?'

Mofidul Hoque is a Trustee of the Liberation War Museum.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments