'The numbers on our list might only be the tip of the iceberg'

Anghkhana Neelapaijit, Asia and Pacific expert and member of the UN Working Group on Enforced or Involuntary Disappearances, speaks about their work regarding enforced disappearances, the situation in Bangladesh, and their recommendations going forward, in an exclusive interview with Ramisa Rob of The Daily Star.

What is the UN WGEID's process of investigating and reporting on victims of enforced disappearances in Bangladesh?

We work strictly under the UN humanitarian mandate and, as a working group, we function like a channel between victims of enforced disappearances, their families, and government bodies. We examine the cases that come to us directly when family members of victims, or lawyers and sources connected to victims, file a complaint with us via our email. The procedure mandates that all victims and family members provide their consent for us to conduct the transmission to the government body. This has been the process we have deployed for the report in Bangladesh as well as other nations. When the government provides us with information regarding the fate and whereabouts of the victims – for example, if some have already passed away, or they are detained – we relay that information to the families. However, we don't close cases if victims' families have any doubt on the fate and whereabouts of the victims that are still unknown after the response from governments.

Regarding the Working Group Method of Work, if sources provide new or updated information on a case that has been previously clarified, archived or discontinued, the Working Group may decide to transmit the case to the State anew and request them to comment. A case can also be reopened if the State's reply referred to a different person, and does not correspond to the reported situation or has not reached the source within the six-month period. In such instances, the case in question will be relisted among those outstanding.

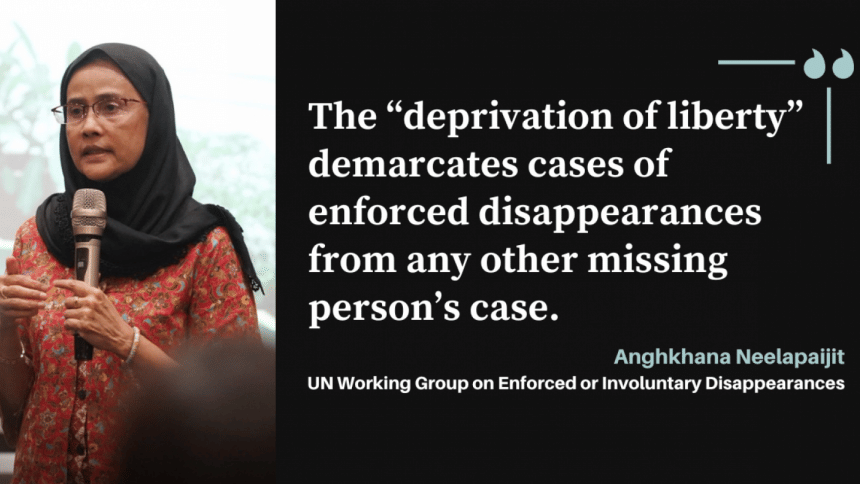

Previously, in response to the UN WGEID report, the Bangladesh government had responded that it is "unlawful to arbitrarily consider a missing person's case as enforced disappearance." What is your response to that? How do you define enforced disappearances?

Regarding such cases, we follow the specific definition stated in Article II of the International Convention for Protection of All Persons from Enforced Disappearance and the preamble of the 1992 Declaration. Their definition states that "enforced disappearance" is "considered to be the arrest, detention, abduction or any other form of deprivation of liberty by agents of the State or by persons or groups of persons acting with the authorisation, support or acquiescence of the State, followed by a refusal to acknowledge the deprivation of liberty or by concealment of the fare or whereabouts of the disappeared person, which place such a person outside the protection of the law."

It is a very comprehensive and specific definition and I want to stress on the "deprivation of liberty," which demarcates cases of enforced disappearances from any other missing person's case. It means nobody knows where they are but their families suspect they are in danger, under arrest or detained by State officials. When the "fate and whereabout" is cleared from the case, meaning the families can access victims, then the victim is not considered "disappeared" anymore. Governments can say it is unlawful but we followed the Convention's definition.

In September 2022, the UN WGEID reported five new cases, two of which were considered "time-sensitive" or "urgent procedures." Can you clarify what that means?

So, urgent procedures or "time sensitive" cases of enforced disappearance are ones that have occurred within the three months prior to the receipt of a report by the Working Group. These cases are transmitted to the State concerned through the most direct and rapid means possible. Cases that have occurred prior to the three-month limit, but not more than one year before the date of their receipt by the Secretariat, provided that they had a connection with a case that occurred within the three-month period, may be transmitted between sessions by letter upon authorisation by the Chair-Rapporteur. The Working Group notifies sources that an urgent action has been sent to the State concerned, thus helping relatives or the sources to enter into communication with the relevant authorities.

Has the situation improved in Bangladesh and are there any outstanding cases currently?

Enforced disappearances in Bangladesh increased since 2018. The outstanding cases today, from my knowledge, have actually decreased to around 70 cases. The Bangladesh government has worked with us to clear the cases and we hope they will continue doing so. There have also been new cases filed this year. It's also important to note that sometimes cases close and can reopen when the victims get re-arrested or when there's new information. The numbers of cases also vary from nation to nation in Asia. For example, in Thailand there are around 76 cases while in the Philippines and Indonesia there are 590 and 178 cases, respectively.

Most importantly, we should keep in mind that the numbers might be only the tip of the iceberg. They are ones that have been reported and filed to us. Oftentimes, victims' families don't even file cases fearing retaliation or some are unaware of this channel through complaint forms. We believe the real picture of the situation anywhere is not reflected by the number of cases.

What are your recommendations for Bangladesh going forward?

First, we hope the Bangladesh government continues to work with the Working Group's procedures to clarify the outstanding cases. Secondly, we have urged the Bangladesh government to allow us to conduct a country visit for the past ten years. We have sent requests since 2013, but they have not accepted it yet. A country visit would allow us to understand more about the legal system, the real situation – to meet with victims' families, and all stakeholders, and conduct thorough investigations independently and impartially. The Working Group can then give thorough recommendations to the Bangladesh government. We hope that after our forthcoming report, the Bangladesh government will allow us to do a country visit.

Thirdly, we remain concerned regarding the suppression of NGOs, lawyers, or other organisations who act on behalf of the victims such as Odhikar. It's also not just Odhikar that has faced this harassment; it is commonplace in many nations. We recommend the Bangladesh government to strengthen the measures to punish perpetrators and reinforce effective measures to prevent the harassment of organisations that report on human rights.

Last, but not the least, we hope the Bangladesh government will take the crucial step of ratifying the International Convention for Protection of All Persons from Enforced Disappearances (ICPPED). By doing so, Bangladesh will become a State party to the convention. The UN committee will then be able to investigate the country's situation. This step will ensure that there is separate investigation and rehabilitation, and measures for effective remedies including psychological remedy. The ratification will also ensure that the country enacts an organic law that complies with the ICPPED to protect victims of enforced disappearances. This is important for countries like Bangladesh, where there are no organic laws specifically protecting victims of enforced disappearances.

Since 2018, numerous recommendations by the Universal Periodic Review (UPR) have urged Bangladesh to ratify the Convention. The ratification would be a very important step for Bangladesh to demonstrate commitment to eradicate enforced disappearances and strengthen the legislative framework on enforced disappearances, in terms of prevention and protection. We hope in the next UPR review later this year, Bangladesh will accept the recommendations to end this crime against humanity and commit to protecting all people in Bangladesh.

Views expressed in the article are author's own.

Follow The Daily Star Opinion on Facebook for the latest opinions, commentaries and analyses by experts and professionals.

To contribute your article or letter to The Daily Star Opinion, see our guidelines for submission.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments