Assange may be in the dock, but it is journalism that’s on trial

During the 78th United Nations General Assembly (UNGA) on September 18-22 in New York, Brazilian President Lula Da Silva and Honduras President Xiomara Castro called on the US and the UK for the release of WikiLeaks founder Julian Assange. To the applause of world leaders, Lula said, "Preserving press freedom is essential… A journalist like Julian Assange cannot be punished [for] informing society in a transparent and legitimate way." Yet, it is these same world leaders – many of them, at least – who are often found to be involved in the persecution of journalists.

The US itself is often considered – and frequently claims – to be a world leader, particularly when it comes to upholding and defending human rights and freedom of expression. Which again makes its persecution of Assange all the more ironic and especially dangerous.

From the very beginning, the Assange case has been fraught with many inconsistencies and controversies. One doesn't have to be a legal expert to realise that the Swedish, UK, US and other authorities have handled the Assange case differently time and again. It almost seemed as if some powerful force was out to get him no matter the cost, and was willing to bend or break all the rules to do so.

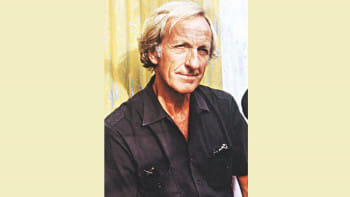

According to Pilger, Assange's crime was that "he broke a silence." Pilger claimed that "no investigative journalism in my lifetime can equal the importance of what WikiLeaks has done and the public service it has provided in calling rapacious power to account." A bold claim, indeed.

In fact, according to legendary journalist John Pilger, a plan was conceived as early as 2008 by the cyber counterintelligence assessment branch of the US Department of Defense with the aim to destroy "the feeling of trust that is Wikileaks' centre of gravity." After 2008, endless information has come to light showing how some of the most powerful organisations in the world have been out to get Assange. The most outlandish among these is the fact that senior Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) officials during the Trump administration's tenure had discussed abducting and even assassinating Assange, while he was still within the confines of the Ecuadorian embassy in London – in clear violation of numerous international laws and treaties.

So, why take such a risk? What is Assange's crime that the CIA contemplated risking an international outcry to destroy just one publisher and journalist?

According to Pilger, Assange's crime was that "he broke a silence." Pilger claimed that "no investigative journalism in my lifetime can equal the importance of what WikiLeaks has done and the public service it has provided in calling rapacious power to account." A bold claim, indeed.

But he is not the only respected human rights defender to have made such a claim. Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist Glenn Greenwald once described WikiLeaks as being "one of the very few, if not (the) only, group effectively putting fear into the hearts of the world's most powerful and corrupt people." Other famed individuals such as Noam Chomsky, Slavoj Zizek, and Nobel Peace Prize winner Mairead Maguire have vehemently applauded Assange for his journalistic achievements.

Yet, aside from the injustices that have been perpetrated against Assange, the case against him and WikiLeaks is much more important for what it might entail for press freedom itself. From Amnesty International to Human Rights Watch, from the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) to the International Federation of Journalists (IFJ) and Reporters Without Borders (RSF), all the important organisations have condemned the prosecution of Julian Assange, denouncing its devastating impact on journalism and on the public's right to know.

Firstly, the very notion that the US can indict and demand the extradition of a foreign journalist is extremely dangerous. It means that sovereignty has no value. And, of course, there is no reason why other countries or governments wouldn't follow suit. In fact, many authoritarian governments around the world have been increasingly doing so. This case in particular could set the most important precedent for extraterritorial prosecution of media across the globe.

Additionally, if Assange is prosecuted for publishing leaked classified documents, every single media outlet is at risk of prosecution for doing the exact same thing. The Obama administration, for example, explored for years whether it could criminally charge Assange and WikiLeaks for publishing classified information, only to decide that it could not do so given the press freedom guarantee of the US Constitution's First Amendment. There would be no way to differentiate a traditional media outlet such as The New York Times or The Washington Post from an entity like WikiLeaks without involving the government and the courts in the formulation of a legal definition of what qualifies as a part of the press. And would we really want that, given the numerous risks that could arise from such a scenario?

This is why even the editors and publishers of The New York Times, The Guardian, Le Monde, Der Spiegel, and El Pais – not all of which are fans of Assange – have said in a letter that his "indictment sets a dangerous precedent, and threatens to undermine America's First Amendment and the freedom of the press."

But, as things stand, Assange's extradition to the US might be imminent. His legal team has filed a final application for appeal, the last option available in the British courts. If accepted, the case could proceed to a public hearing in front of two new High Court judges. If rejected, Assange could immediately be extradited to the US, where he will stand trial for 18 counts of violating the vague Espionage Act, and face charges that could see him receive a 175-year sentence. As RSF said in a statement on June 8, "The historical weight of what happens next cannot be overstated."

Therefore, regardless of one's personal feelings towards Assange or his organisation, WikiLeaks, it is high time for anyone who believes in the importance of press freedom and of protecting journalism to realise that, while Assange sits in the dock, journalistic rights and press freedom are truly the ones under trial and in grave danger.

Eresh Omar Jamal is a freelance journalist.

Views expressed in this article are the author's own.

Follow The Daily Star Opinion on Facebook for the latest opinions, commentaries and analyses by experts and professionals. To contribute your article or letter to The Daily Star Opinion, see our guidelines for submission.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments