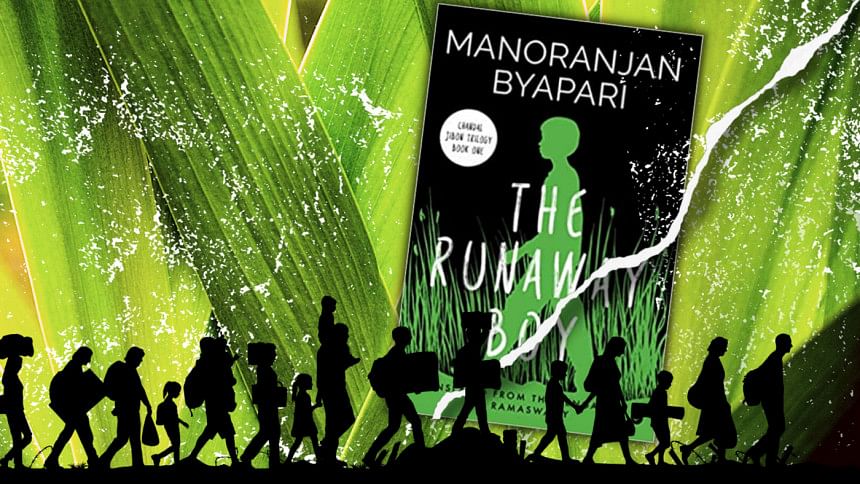

The Runaway Boy: A promise not delivered

The Runway Boy (Eka, 2020), written by Manoranjan Byapari and translated from Bangla by V Ramaswamy, delivers an accurate portrayal of postcolonial Bengal, with all its socio-economic issues centering on casteism, inspired to a great degree by Byapari's own life and struggles.

Jibon, the protagonist of Byapari's semi-autobiographical trilogy, arrives at a refugee camp in West Bengal as an infant in the arms of his Dalit parents, shortly after the Partition of 1947. His birth forecasts the shadow of struggles that his life would be, engulfed in poverty and perpetual hunger, deprived of the customary sweetness of a few drops of honey at birth, which too, is arranged after the many hurdles that his poor father, Garib Das, has to face.

At barely 13, Jibon runs away to Kolkata with hopes and dreams glimmering in his eyes. Money flies in the air in the big city, he hears. His naive imagination makes him believe that he can go out into the world, find work, and bring back food for his starving family. However, more struggles await him as he leaves home and goes out to face the real world by himself, in a newly independent India grappling with communalism and caste disparities.

The book starts by painting a quintessential image of rural Bengal. "It was dawn. Crimsoning the eastern sky, the sun emerged like a golden orb over East Bengal's marshlands." "A flock of cormorants flew across the sky, their wings unhindered and free. Who knew where and how far they would take them!" Byapari writes of Jibon's life as it unfolds.

The narrative, however, starts to lose that nuance when the metaphors are stretched further, depriving readers of the chance to make their own interpretations of the text. "The man was now walking westwards," is how a paragraph starts as it describes Garib Das, Jibon's father. But it continues, "The east is associated with sunrise and the west with sunset. That symbolic description was apt for the way the man walked. He dragged his body along, like the beast of burden. He seemed to be walking towards his final conclusion—a solitary journey, on which there could be no companion." Such unpacking of metaphors, word-by-word, overly simplifies the text, which takes away the magic of reading into the story.

Byapari, however, makes up for this through his adept foreshadowing of important political events. Shibnath Bhattacharya, an upper-caste, privileged Hindu man, stays back in East Bengal even after most of his family has migrated to the west during the Partition. However, he regrets the decision during the Liberation War of 1971 when religious minorities (including Shibnath's family members), mostly belonging to the Hindu community, are brutally persecuted by the Pakistan military. The book transcends time to make this forecast of the persecution of minorities, which is still relevant in the context of the subcontinent.

The translation seems like an extension of the original, rather than a work on its own. Paragraphs after paragraphs are repeated in the original Bangla text written in English alphabets, failing to render the essence of the original text, making it a rather difficult read for non-Bangla speakers.

The way the characters—and there are many—are developed in each chapter alongside the protagonist's journey through his life intrigues the reader, but it fails to keep them hooked. Some details are irrelevant and are detached from Jibon's story, adding almost nothing to his journey. These characters don't reach a conclusion of their own either, and it feels as if their purpose was only to strengthen the writer's point on the ply of the existing inequality in the picture of the society that he's trying to paint.

The questions surrounding casteism, classism, and inequality are raised with utmost conviction in this novel, but it feels as though they lack the soul to keep the story going, and contribute very little to that purpose. They take so much away from the protagonist, Jibon Das's journey, that it leaves the readers wanting for more details from his end, and for a closer peek into his psyche. The book seems more like a manifesto than a work of fiction, and this is what ultimately takes away from the initial interest that is piqued in readers and the promise that it offers.

Nahaly Nafisa Khan is a former sub-editor at The Daily Star's City Desk.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments