Understanding the maverick politician, AK Fazlul Huq

Fazlul Huq is a largely forgotten politician in West Bengal. The apparent indifference towards Huq in West Bengal or India can be partly explained by the unfortunate vivisection of India in 1947. In other words, the Prime Minister of undivided Bengal has become a victim of Partition.

Valuable insights into Muslim politics and the multifaceted activities of this versatile politician, recognized as a mass leader, can be found in the writings of Humayun Kabir (in Muslim Politics: 1906-47 And Other Essays, Calcutta, 1969) and D.N. Banerjee (in East Pakistan: A Case Study in Muslim Politics, Delhi, 1969). However, it is challenging to chronicle Huq's political life in a chronological and uninterrupted manner solely by relying on these insightful works. Readers would greatly benefit from consulting a work entitled Jukta Banglar Sesh Adhyay (meaning 'The Last Chapter of United Bengal,' written in Bengali, Calcutta, 1966) by the eminent journalist Kalipada Biswas.

This book is renowned for its detailed description of Huq's political life. Huq, a broad-minded, non-communal politician, is not clearly portrayed by J.H. Broomfield (in 'Elite Conflict in a Plural Society'). Huq's political activities can be linked to a larger process: the quest of Bengal Muslims for identity and recognition within the constraints and complexities of colonial rule. There are certain similarities as well as differences between Huq, a Bengali-speaking politician, and other non-Bengali leaders of the Muslim League, which should be studied within the socio-economic contexts to gain a proper understanding of Muslim politics in Bengal and its linkages with all India politics. It would be highly relevant to assess the influences of Ashwini Kumar Dutta, Sir Ashutosh Mukherjee, W.W. Hunter, and last but not least, the Bengal countryside on Huq. Historical scholarship still awaits such a comprehensive endeavor.

After the suspension of the Bengal Partition in 1911, Muslim leaders rarely dared to contest elections in areas dominated by caste Hindus. However, Huq was a new type of leader who could be distinguished from the Muslim Nawabs or the landed aristocracy. Unlike his political predecessors, Huq could communicate with the people in their colloquial dialect and, hence, could feel their pulse. In 1913, this dynamic politician became a member of the Bengal Legislative Council. Blessed by Ashwini Kumar Dutta, Huq defeated Rai Bahadur Mahendranath Mitra in the Dacca constituency in the same year. Huq crossed another milestone in his political career with the passing of Sir Salimullah in 1914. He then led the Muslim League in Bengal while simultaneously retaining his leadership position in the Indian National Congress.

One noticeable aspect of Huq's leadership was that even before the advent of Gandhi in Indian politics, Huq, as a farsighted politician, could anticipate the necessity of mobilizing the masses. Historians may continue to debate whether his emotionally charged speeches were strategically engineered to mobilize the masses or a genuine concern for their uplift within the constraints of colonial rule. However, none would question his ability to rally the masses. Huq reiterated that "British rule and our rulers have not only sucked the Indian orange juiceless, but the chances are that if they are not pulled up in time, even the rind will not be left over for the Indian people." Indeed! R.C. Dutt's famous 'Drain Theory' is resonated in this statement.

A brilliant student of Presidency College, Huq was well-read and represented the emerging, enlightened Muslim middle-class. Despite his significant success in the urban milieu, Huq never forgot his ancestral district, Barisal, in Eastern Bengal, which continued to play a key role in his political activities. In another sense, we can recognize Huq as a pragmatic politician. He could apparently measure the strength of his potential rivals in all India politics and concentrated on the province (Bengal in his case) as the epicenter of his political career.

As a politician, Huq was not free from contradictions and complexities, which must be interpreted in the context of the complex circumstances he encountered during the high age of colonialism. For instance, despite his association with the Muslim League, it would be inappropriate to label him as a communal politician. In support of this hypothesis, we could argue that he attempted to identify oppressors in Bengal not based on someone's religious affiliation, but on their public role. Following this trajectory, he strongly criticized money-lenders, lawyers, and both Hindu and Muslim landlords for their oppressive and exploitative practices. Incidentally, the majority of zamindars in Bengal during his time were Hindus, and the majority of peasants were Muslims, particularly in Eastern Bengal. Huq did not single out the Hindu zamindars as oppressors. He did not accuse any particular religion or community for the outbreak of communal violence in the subcontinent. He endeavored to be objective, pointing out that 'These disturbances are due to the fanaticism and ill-conceived religious fervor of those sections of the two communities who, due to lack of education and other causes, have not learned to be tolerant of the feelings and sentiments of others.'

He also envisaged the struggle against colonialism as a joint venture involving both Hindus and Muslims. He believed that if Indian Muslims took a positive and unselfish approach to this issue, they would realize the importance of cooperation with their Hindu brethren. Even if they took a rather negative and selfish approach to this issue, they would recognize that cooperation would be necessary for self-protection. Huq observed that some Muslims took pride in showing intolerance towards non-Muslims. He believed such an attitude was not politically acceptable because all Indians should unite to fight against arguably the most powerful bureaucracy in human history.

In 1915, Huq attempted to unite the Muslim and Namasudra peasantry of Barisal. Unlike the Ali brothers or Abul Kalam Azad, he opposed the Khilafat Non-Cooperation Movement, largely because he believed that the boycott of schools, which became part of the program, would yield adverse results.

Although Huq held a leadership role within the League, he channeled his full energy into the Krishak Praja Party, which was his party. The term 'Praja' became significant, particularly because of its inclusive nature. It represented not only the peasants but also the middle-class population. The term 'praja' thus became acceptable to the educated middle-class. Huq's party was also under middle-class leadership. During the initial phase, the League leadership was entirely different in nature due to its aristocratic bias. Jinnah, for an extended period, preferred to function as a drawing-room politician.

Normally, the League conducted its work in the English language, with matters being translated into Urdu when necessary. An 'All Bengal Urdu Association' was formed, which essentially served as a mechanism for non-Bengali leaders to control the cultural life of Bengal's Muslims. By controlling cultural life, this leadership aimed to control Bengal's politics. More precisely, non-Bengali leadership intended to utilize the large constituency of Bengal to fulfill their all-India ambitions. Herein lies the fundamental difference between this leadership and Huq. The latter was keen on safeguarding the interests of Bengal comprehensively.

The non-Bengali leadership claimed that the essence of Islam couldn't be conveyed through the Bengali language and that Urdu was the suitable medium. The roots of the language movement in post-Partition East Pakistan can be traced here. It's not surprising that in the 1950s, Huq sided with Bengali students in East Pakistan who sought to preserve the honor of their mother tongue. The Language Movement of 1952 wasn't merely a movement to preserve the dignity of the Bengali language against the brutal assaults perpetrated by the Pakistani regime. It became a symbol of a much larger struggle for the Bengali-speaking people of East Pakistan who sought emancipation from political, economic, and social subjugation. Huq, along with former League stalwarts such as Bhashani and Suhrawardi, became pioneers in that struggle.

We must note the heterogeneity among the non-Bengali leadership regarding their attitude toward the Bengali language. For instance, the eminent leader Aga Khan believed that the vernacularization of Islamic knowledge could actually promote the process of Islamization, recognizing Bengali as a rich and vibrant language. Still, in 1934, Aga Khan included only one Bengali member in the Executive Committee of the All India Muslim Conference. No Bengali was considered either as the president or secretary of the All India Muslim League. The staunch pro-Urdu group largely ignored Aga Khan's advice regarding Bengal and the Bengali language.

While Huq sought recognition of Urdu at the all-India level, he opposed plans to replace Bengali with Urdu in Bengal. Huq's liberal, non-communal approach and his commitment to serving the economic interests of the commoners were evident in the program set by the Krishak Praja Party (KPP). For example, the KPP demanded the abolition of oppressive acts such as the Bengal Criminal Law Amendment Act and the Public Security Act, the development of small-scale industries, the establishment of the lowest price for jute, free and compulsory primary education, the fixation of the minimum wage for workers, the prevention of illegal exactions by zamindars and money-lenders, water supply in villages, improvements in the condition of domesticated animals, and agriculture, among other things. For this people-centric program, many Hindus and Muslims were active in the KPP.

Despite his significant success in creating a mass base in Bengal, Huq did not have a smooth ride in the political arena. Pro-Jinnah League leader Ispahani allied with Suhrawardi to curb Huq's influence, using the Muslim League Parliamentary Board for this purpose. They systematically attempted to tarnish Huq's image by claiming he received regular financial support from Hindus. How did Huq respond to these nefarious efforts? Instead of relying on a communal character, Huq, like a modern, secular politician, aimed for his speeches and actions to acquire a class dimension. He firmly pointed out, "My fight is with landlords, capitalists, and vested interest holders. The landlords are 95% Hindus, and capitalists and others are about 98% Hindus. Far from supporting me, they are already trying to obstruct my path… In the near future, they will join hands with their Muslim compatriots, namely Muslim landlords, capitalists, and others, to thwart me."

In this context, it's worth noting that the Muslim League didn't propose the abolition of the Permanent Settlement until 1935, nor did the Congress contemplate forming a separate organization for the peasantry. In the 1937 election, Huq defeated the League, and there was an improvement in Congress's performance in the election as well. However, the myopic central leadership of the Congress failed to realize the importance of forming a coalition ministry with the KPP. Huq was unprepared for this situation.

In that critical juncture, shrewd Jinnah instructed his followers to accept the Huq-League Coalition Ministry, with Fazlul Huq as the leader. Jinnah had the ambition to control the important province of Bengal, and Huq aspired to be its Premier; here, the interests of the two great leaders converged. However, Huq was opposed to the Two Nation Theory, staunchly put forward by Jinnah and his followers. For example, Huq delivered a lengthy speech in Calcutta on January 8, 1942, to commemorate the fifty-eighth death anniversary of the great eclectic Brahmo leader Keshab Chandra Sen, who can be regarded as a pioneer of comparative religious studies in modern South Asia. On that occasion, Huq pointed out, "There is no real diversity in religion. All religions must be one… The future of India would be decided not by strife but by harmony, and those who tried to bring about harmony and concord would be the greatest benefactors of the country." Of course, the League leadership became suspicious of Huq's activities and tried their best to isolate him politically.

Huq stated that the League had lost its relevance and expressed his desire to establish a progressive Muslim League at the all-India level. An organizing committee was set up in Calcutta, with the Nawab of Dacca as President and Syed Badruddoza as the Secretary. In this context, Huq reiterated, "Unity between Muslims and other communities is a fundamental necessity for the political advancement of India." However, neither the Congress nor the left parties could utilize the potential of this politician for India's freedom struggle. On the other hand, the ruthless League leaders, under the indulgence of Jinnah, made an all-out effort to curb his political influence. India's slide toward vivisection accelerated.

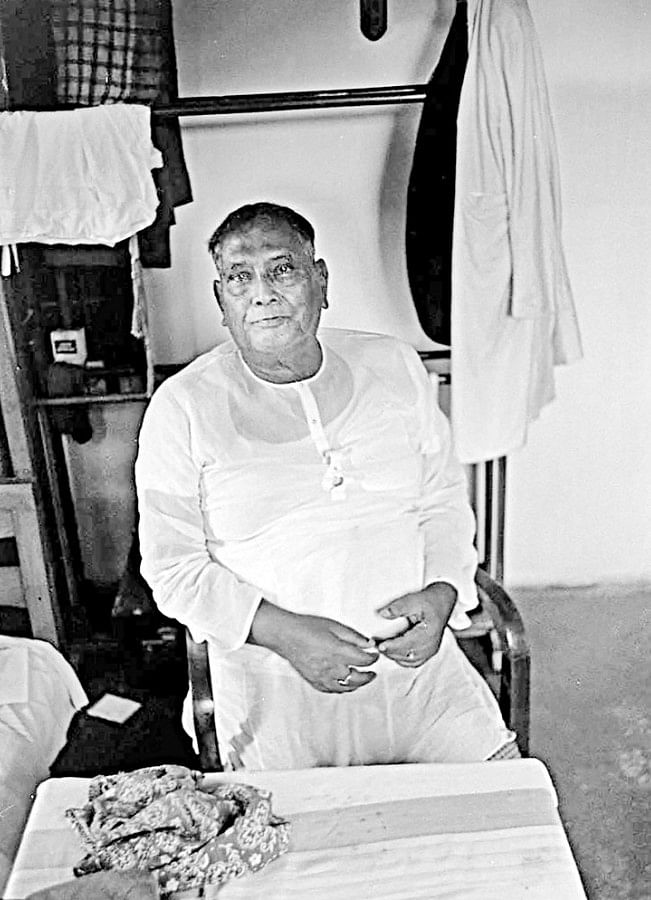

Furthermore, my discussions with my parents, a few months before their passing, were of great help to me. I have consulted several books written by my father Amalendu De. My mother, the late Mrs. Naseema Dey, was the granddaughter of Mr. Fazlul Huq. Sir Ashutosh held a deep admiration for Huq. I never imagined that one day I would hold the position of Sir Asutosh Chair Professor and write about my ancestor.

Dr. Amit Dey holds the position of Sir Ashutosh Mukherjee Professor of History at the University of Calcutta

References and Acknowledgements:

- Amalendu De, Pakistan Prostab O Fazlul Huq

- Amalendu De, Islam in Modern India

- Chandi Prasad Sarkar, Bengal Muslims, A Study in their Politicization

- Amalendu De, Svadhin Bangabhumi Gathaner Parikalpana: Proyas O Porinoti.

- Amalendu De, Bharate Muslim Rajnitir Gati Prakriti.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments