Can bureaucrats be neutral in a win-or-lose-all battle?

Let me put it another way: is a fair election possible even if Awami League "allows" it? On Tuesday, Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina again snubbed calls for dialogue with BNP, reiterating her decision to hold the upcoming election under the incumbent government. This comes amid a countrywide "blockade" being enforced by the opposition demanding precisely the opposite: her resignation in favour of a neutral election-time government. However improbable it may seem now to picture a solution that satisfies both camps, imagine, for a moment, a scene where both have somehow found a way past their differences and are preparing for a fair election.

What then? Can we finally have that Holy Grail of our politics? An election is, by nature, fluid, a change in and of itself. Parties come and go (or they used to when there was still a functional democracy), the Election Commission can be formed and re-formed as needed, and the allegiance of voters and other pockets of power, local and foreign, is seldom guaranteed. Everything is in flux. If there is one constant in this sea of variables, it is bureaucracy, the executive arm taking care of the business end of elections. Barring the minor inconvenience of transfers for some, bureaucrats are the ones that remain firmly in place regardless of who sits at the helm of the election-time government or the one that follows it. And how they act may hugely impact the outcome of any election.

So, come January, will a fair election be possible if all the parties can resolve their differences? I would like to argue that it won't be—not at least to the degree that we have come to expect based on our experience of 2008, the last time when Bangladesh witnessed a relatively fair election. And it is because bureaucracy has gone through a sea of change since then.

Before 2008, bureaucracy experienced what we can call a cleansing during the 23-month-long state of emergency, enough to shed any residual inhibitions about resisting political influence. And it helped the election. After 2008, however, no longer shackled by the military, it again moulded itself around the needs and desires of a political administration. Imagine what 15 years of constant moulding and politicising can do to a system or the people behind it.

To its credit, Awami League knows the long-term value of bureaucrats. Despite frequent objections raised about bureaucratic overreach and the overdependence on public officials, including by some of its own MPs, the party has done little to address them. On the contrary, it has continued to empower them across the board, constantly priming them or programming their subconscious through various incentives and protective safeguards (legal/administrative), and that has richly rewarded the party during the last two general elections. A quick look at some of these measures really baffles the mind.

Think of when the Awami League government passed the Public Service Act, 2018, preventing law enforcement agencies from suing or arresting government employees without prior permission, basically giving them indemnity against any crime or corruption committed. Its support for police or Rab, in the face of multiple allegations of crimes, has been swift and unconditional. It has also variously integrated state officials into the power structure, at times replacing local-level politicians as heads of various relief committees. Or think of how, during its three consecutive terms in office, the government has showered them with many perks and privileges including massive pay hike, easy loan terms, tax exemptions, and "gifting" of plots in some cases. This trend seems only to have intensified in the months leading to the 2024 election.

On October 12, The Daily Star reported a controversial move by the Cabinet Committee on Economic Affairs that approved the purchase of 261 expensive cars for the DCs and UNOs at a cost of Tk 381 crore, adding to the strain on public coffers at a time of record-high import bills and critically low forex reserves. What message could the government be sending to the DCs and UNOs—who usually serve as returning officers and assistant returning officers, respectively, during elections—through such pleasing tactics so close to the election? Around the same time, we have seen similar, strategically timed provisions in the form of in-situ promotions at the public administration ministry, or supernumerary posts created at the top level of police. The question is: can public officials, especially those performing election-related duties, still act neutrally when the time comes?

Their likely reaction—doing Awami League's bidding on its behalf, even if they are not expressly asked to—can be attributed to three possible reasons. First, because of the numerous perks, privileges, concessions and exemptions many have enjoyed over the years, they may feel motivated to help out of their own selfish desires. Second, public officials associated with the police and other vital administrative wings, who have been involved in harassing and silencing opposition leaders and activists, may fear retribution should the latter come to power. This can be a powerful motivator for them to want to retain the status quo, especially given speculations that cops with records of political repression were being "listed." Third, the stringent political screening that usually precedes any recruitment or promotion in the public service, especially important government positions, means that a large number of officials are already loyal to Awami League—or at the very least, unsympathetic to its archrival, the BNP—and may naturally try to prevent any possibility of "their" party being ousted from power.

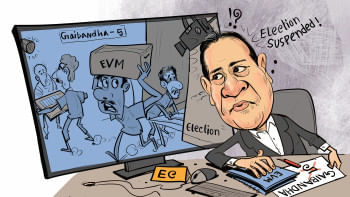

These are not merely hypothetical concerns, however. Over the years, the politicisation/programming of bureaucracy has been so unrelenting that sometimes local-level officials have been found to be openly campaigning for ruling party candidates. Other times, like during the suspended Gaibandha-5 by-election in October 2022, their irregularities and wilful negligence in electoral duties were more impactful. There have been too many brazen displays of political loyalties to treat them as isolated incidents. If the past is any indication, it will be unwise to expect a different response come January, especially when the political stakes are so high.

We're already witnessing how the government is again using state apparatuses to clip the wings of arrested/accused opposition members, including by rushing trials through unprecedented night-time hearings, in a potential bid to keep them away from the election. Police are supplying fodder by arresting left and right. It almost feels as if bureaucracy has become an extended appendage of the ruling party.

So, before we talk about reforming the electoral process, or ask Awami League and BNP to hold dialogue over the composition of any interim government, perhaps what we should be asking is whether the interests of our largely pliant, grateful, and politicised bureaucrats are aligned with the public expectations for a fair and participatory election. We must understand how far the rot has spread in the last 15 years before seeking remedies for it.

Badiuzzaman Bay is assistant editor at The Daily Star.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments