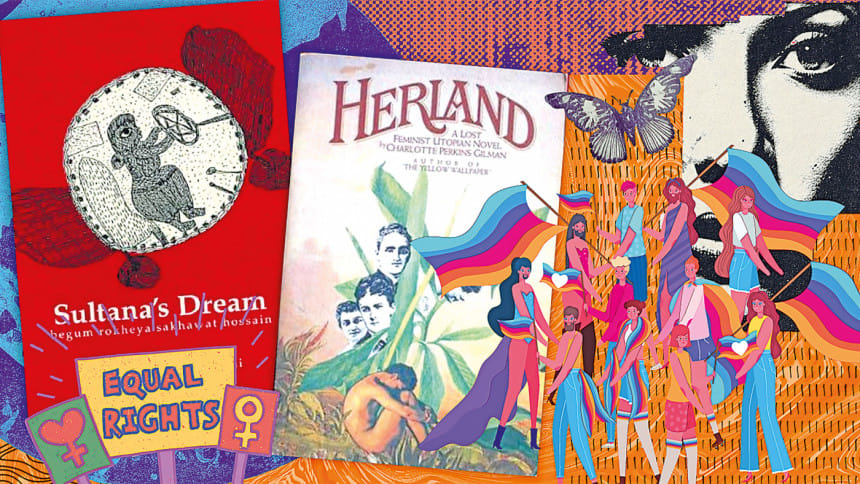

Sultana’s Dream and the issue with feminist utopias

"They should not do anything, excuse me; they are fit for nothing."

Such was how Sister Sara, a character in Begum Rokeya Shakhawat Hossain's novella Sultana's Dream (The Indian Ladies Magazine, 1905), perceived men. It is, indeed, the tone that the whole piece of work adopts towards men, viewing them as vermin in a world where they are unwanted and uncared for. While it is consistently hailed as one of the finest works exploring the possibility of a feminist utopia, I am very reluctant to label it as such.

The world of Sultana's Dream is essentially one that arises due to the reversal of gender roles. Men are oppressed, the society is technologically and structurally advanced as a result of women ruling. However, it does not feel utopian. A utopian society should be one where everyone feels fulfilled, not one where a group of people continues to be oppressed by virtue of their biological sex.

Feminism is a movement rooted in the search for equality, and a feminist utopia should be one where all people exist on an equal footing. All this is not to say I don't understand why Begum Rokeya adopts such a radical view. The extreme forms of purdah and gender inequality that she and her contemporaries had to endure surely made her deeply angry, which took root in her near-vindictive narrative. It is an important piece of feminist history, but calling it a brilliant feminist utopia is not entirely justified.

In her less well-known works, Rokeya appears less zealous about the eradication of the male species and more open to the idea of an equal society, free from the bonds of gender and sex. In Motichur (1904) and Padmaraag (1924), she openly advocates for the abolition of gender-specific norms. The undercurrents of the dream of a feminist utopia can still be seen in her wish for a female-led governing body. But those wishes do not metamorph into misandric desires.

Annie Denton Cridge's satirical work Man's Rights; or, How Would You Like It? (Woodhull and Claflin's Weekly, 1870) takes a similar form to Sultana's Dream. Cridge spends the first part of the book describing dreams about a Martian society where every gender stereotype is reversed, giving vivid imagery of the mistreatment Victorian women faced by thrusting said mistreatment upon men. She then follows this with a pair of dreams about a reformed world where men and women together lead a balanced life. Cridge's ultimate utopia does not rely on the degradation or disenfranchisement of men; rather, it rests on women taking charge of their fates and fighting for equity in socio-political standing. It tackles the same themes as Sultana's Dream. But, by placing a picture of equality side-by-side with a picture of feminine radicalism, it presents the question: "What should a feminist utopia truly look like?"

Over the years, countless authors have tried to answer this question. I feel, however, that most have failed in creating a truly captivating, fulfilling world. In Charlotte Perkins Gilman's Herland (The Forerunner, 1915), the idea of a self-propagating, supportive community is tainted by the author's persistence on a racially pure group of females. In portraying a society where white women are living a happy, isolated life, the book entirely ignores the struggles of women of colour. In celebrated author Ursula L Guin's The Left Hand of Darkness (Ace Books, 1969), a seemingly androgynous, same-sex society is continuously referred to by the "he/him" pronouns, breaking the fantasy of a world beyond biological sex. Many of these worlds seem concerned with the few men that survive after a calamitic event wipes out the others and the fates they suffer as a result of being endangered, such as in Afterland (Penguin Random House, 2020), instead of focusing on the utopian aspect itself.

Most feminist utopias argue some form of feminist separatism, a concept that is harmful to the overall feminist movement because of its historic exclusion of transgender and transexual individuals. Feminist utopian worlds do suffer from an erasure of trans identities. They are fundamentally based on the biological definitions of sex, giving rise to trans-exclusionary radical feminism (TERF).

Additionally, these worlds promote gender essentialism which is rooted in the belief that certain values are possessed by certain people because of their biological sex. In Sultana's Dream, for example, being timid is considered akin to being mannish. With the reversal of gender tropes, this means that all females are considered as being timid and meek. In Herland, the society is prosperous because of feminine prudence. A feminist society is supposed to look beyond the confines of the social definitions of gender and sex. But they seem to hold on to these superficial standards even harder. Moreover, the narrative that a world led exclusively by women will be devoid of crimes and wars is too idealistic, particularly given that historical evidence suggests otherwise.

The idea of what a female-centric world could look like is a vastly interesting concept that has, unfortunately, not been executed to a satisfactory degree yet.

Adrita Zaima Islam is a struggling student and writer, and she is trying her best to be the best version of herself. Send her your condolences at [email protected].

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments