'Deeper analysis of internal dynamics within supply chains is crucial'

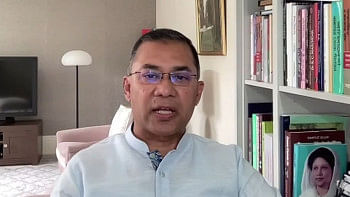

Hossain Zillur Rahman, executive chairman of Power and Participation Research Centre and former adviser to the caretaker government, discusses the nuances of inflation in Bangladesh with Naimul Alam Alvi of The Daily Star.

What are the main factors behind the inflation effecting Bangladesh recently?

It is a reality that market prices fluctuate, but the specific reasons behind these fluctuations can be complex. In Bangladesh, the prevailing perception is that once prices soar, they rarely plummet again. This creates a sense of helplessness among consumers and is a mindset imposed on the market by traders.

Three key stakeholders contribute to this dynamic: producers, consumers, and businesses, with the government acting as an influential backdrop as it wields policy and administrative instruments, significantly impacting market behaviour.

For effective analysis, it is essential to categorise the products under consideration. Domestically produced goods and imported goods have distinct price dynamics and require separate evaluations. In the case of domestically produced goods, there is a need to look at the interests of the farmer or the producer. We need to see what the producer is getting versus how much the consumer is paying—that is, the margin between the two. We also need to examine if the margin is unreasonable. In the case of imports, the business community has a role to play, and so does the government. For example, when the government allows imports, we need to see how much duty is imposed on those.

Inflation in Bangladesh arises from the complex interplay of three main factors: the government's market management, monetary policies, and internal market dynamics.

Not all "middlemen" are villains. Many small traders within the supply chain play a vital role in maintaining product flow and incur economic and non-economic costs for, say, transportation and extortion. These legitimate costs can justify price adjustments. But concerns arise when the adjusted prices are unreasonable or inflated.

In the case of domestically produced goods, the cost increases as they go through the supply chain to reach end consumers. While reasonable margins are expected, evidence suggests that certain groups exploit the chain to gain profits in excess by influencing market management. This lack of discipline stems partly from the potential blurring of lines between the government and interest group representatives who sometimes hold government positions. Consequently, the government exhibits a lack of both intent and capacity for dynamic and responsive market management. Recent years have shown a further decline in both, evident in the absence of thorough price monitoring and interventions. For example, agricultural produce prices traditionally decline during harvest seasons. However, even when farmers receive fair government procurement prices, local influential actors exploit the system, ultimately paying farmers less.

In the case of imported goods, similar market management issues come into play. While the government assumes adequate market supply, it overlooks the specific groups disproportionately affected by inflation.

Again, both the intent and capacity for dynamic and responsive market management fall short. This decline manifests in the absence of comprehensive price monitoring and interventions, further amplified by the aforementioned market psychology.

A chunk of the supply chain is still unorganised and outside the government's scope of monitoring. On the one hand, this gives various groups the opportunity to raise prices, as you mentioned. On the other hand, various reports say that the middlemen are also victims of extortion (and other non-economic factors) and so the risks they face are increasing, which is why prices are also increasing. Is there any way to organise this and bring it under government monitoring?

A nuanced understanding of the issue is crucial. Not all "middlemen" are villains. Many small traders within the supply chain play a vital role in maintaining product flow and incur economic and non-economic costs for, say, transportation and extortion. These legitimate costs can justify price adjustments. But concerns arise when the adjusted prices are unreasonable or inflated.

For example, the recent fuel price fluctuations highlight this dynamic. While global fuel prices dropped, domestic transportation costs remained high, partly due to Petrobangla's profit margins. This translates to increased costs for smaller traders who cannot absorb them entirely, impacting final product prices. So, transportation costs have not decreased, and the traders who keep the supply chain in order are also forced to increase their prices.

The main problem is that there are some big players here who try to manipulate the market using their economic and political influence. They are the ones who unreasonably increase the market prices for specific products in the supply chain, wherever they spot an opening to do so.

It would be wrong to think that the market can be controlled administratively. What we need is an improved market management, which would at first include taking technical measures, such as improving transportation for traders (perhaps by improving the transport sector overall), improving market centres, and improving information flow.

Second is the political aspect. These big businessmen, the middlemen, reduce supply sometimes and increase it at other times, based solely on their own convenience. Essentially, they control supply to increase inflation.

The government should deal with these middlemen politically, administratively and sensibly, since they control a large part of the supply and could create market crises. Faced with consumer pressure, governments often soften their stance towards these influential actors. This is partially due to the power these individuals have amassed within the political system, blurring the lines between economic and political power. Consequently, a critical lack of both intention and capacity arises from within the government to effectively manage the market and regulate these influential figures.

What steps should be taken to control inflation now?

A deeper analysis of the internal dynamics within supply chains is crucial. To this end, I propose the urgent development of an independent and credible white paper focusing on specific critical products like vegetables, rice, meat, edible oil, and baby food. This state initiative should avoid whitewashing and instead facilitate rigorous investigation by independent experts to identify the root causes of inflation, as well as come up with potential solutions. Such analysis must be grounded in real-world conditions, transcending theoretical discussions.

Immediate reactions like market raids or ministerial inspections are unlikely to provide sustainable solutions. Instead, a commodity-specific market management approach is needed, focusing on the aforementioned essential products. This should be achievable even within a month. A white paper for inflation will serve as a test of the government's commitment to transparency and proactive action in combatting inflation.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments