LDC Graduation: Implications for Bangladesh beyond 2026

It is now more or less recognized that Bangladesh is one of the world's fastest-growing and relatively more resilient economies. The country's macroeconomic performance during the pandemic-induced economic slowdown and the ongoing global supply chain disruptions caused by the Russo-Ukrainian war bear testimony to such an inference. Bangladesh's commendable successes in terms of reducing poverty, coupled with its consistent achievements in human development indicators such as the hunger index, average life span, and maternal and child mortality rates, also prove that gains from positive macroeconomic performances have been able to improve the 'quality of life' for those belonging to the bottom of the social pyramid. Yet, it must also be acknowledged that Bangladesh has faced unprecedented challenges related to the external economy and some internal structural issues. The new government faces critical challenges associated with managing persistent inflationary pressures, making the exchange rates market-friendly, managing the financial deficit, bolstering the forex reserve, creating further employment opportunities, improving the investment climate, and enhancing capacities to mobilize revenue.

Bangladeshi policymakers must make quick, potent, and prudent moves to address the above-mentioned macroeconomic challenges to further realize the country's economic potential (e.g., becoming the ninth largest consumer economy by 2030, a trillion-dollar economy by 2035 or 2040, etc.). It must also be remembered that these challenges, though critical, are only immediate ones. Policymakers must not lose focus on the bigger picture as Bangladesh is to become a 'developing country' within another couple of years (by November 2026). This graduation from the 'LDC category' will create an additional set of macroeconomic challenges for Bangladesh that must also be flagged now.

Given this context, analyzing the challenges likely to emerge due to LDC graduation and looking into the possible ways forward are very relevant. The UN General Assembly has rightly set Bangladesh to graduate from the LDC status and officially become a 'Developing Country' by the end of 2026. In 2021, when this decision was made, Bangladesh's GNI per capita stood at USD 1,827 (graduation threshold is USD 1,222). Bangladesh's scores in the other two indicators, i.e., the Economic Vulnerability Index (EVI) and the Human Assets Index (HAI), were also significantly above the graduation thresholds. The country's EVI score stood at 27 whereas the graduation threshold is 32 or below. Bangladesh's HAI score stood at 75 whereas the graduation threshold is 66 or above. These certainly proved that Bangladesh's journey of inclusive and sustainable development over the previous 10-12 years had yielded the desired results. However, this brought up burning questions about the challenges associated with this graduation.

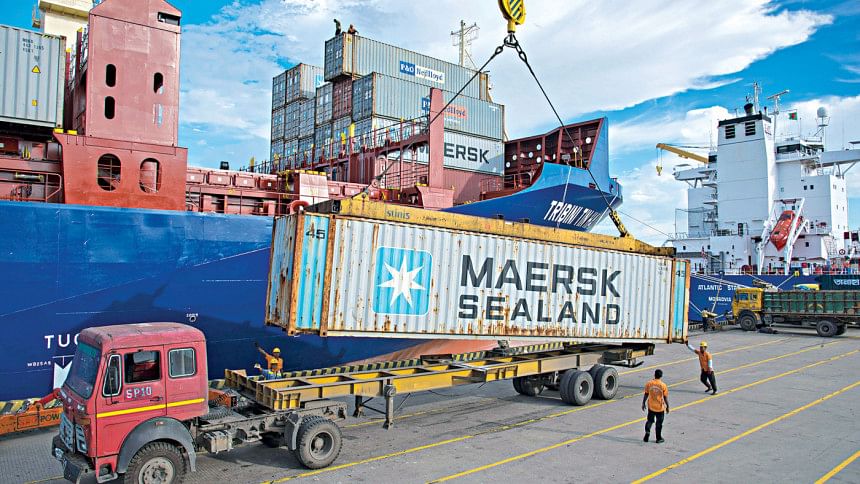

What are these challenges? As an LDC, Bangladesh has enjoyed preferential access for its exports to many countries. This has particularly contributed to the rapid growth of the RMG exports (which have reached almost USD 50 billion annually by now). Graduating may result in Bangladesh losing such preferential treatment. Secondly, as an LDC, the country has remained flexible in implementing intellectual property rights (IPRs). This has significantly benefitted Bangladesh's pharmaceutical and software industries, which have significant growth potential as export-oriented sectors. However, after graduation, Bangladesh must be further stringent in implementing the IPRs. In other words, these industries will then face increased competition in the global marketplace. Finally, Bangladesh has leveraged long-term soft loans from international development partners as an emerging economy. After graduating from LDC status, Bangladesh will have to pay higher interest rates and deal with shorter grace periods for these International Support Measures (ISMs).

All these make it obvious that without revamping the policies and practices related to international trade, Bangladesh may lose its competitive edge to a significant extent once it becomes a 'developing country.' A UNCTAD projection from 2023 shows that the potential loss of export earnings due to losing Most Favored Nation (MFN) tariffs and withdrawal of the Duty-free Quota-free (DFQF) facilities may range from 7 to 14 percent. It must be noted that this will happen if Bangladesh follows a 'business as usual' course even after graduation from LDC status. Commentators and experts remain optimistic that Bangladesh will live up to its reputation as an ever-evolving and resilient economic engine and cope with this new set of challenges. Yet, the question remains: how to deal with these new challenges most effectively? The country, i.e., its policymakers, will have to combat these challenges in two frontiers: negotiations (mainly more brilliant economic diplomacy) at the international level and bolstering capacities at the domestic/internal levels.

Fortunately for Bangladesh and other economies in transition (e.g., Nepal and Lao PDR), the global bodies appear to be sensitized (at least to a significant extent) to these newly emerging economic challenges. The formal statement from the 12th Ministerial Conference of the WTO (publicized in June 2022) states, "We acknowledge the challenges that graduation presents … We recognize the role that certain measures in the WTO can play in facilitating the smooth and sustainable transition for these Members after graduation from the LDC category." Given this backdrop, now seems to be the high time for Bangladesh to go for a three-pronged approach to economic diplomacy in the international arena.

Firstly, Bangladesh needs to collaborate with other LDC countries to ensure that WTO's previously committed LDC-friendly initiatives (e.g., DFQF market access, LDC-friendly rules of origin, etc.) are materialized as soon as possible so that the country may enjoy the full benefits until it formally graduates.

Secondly, policymakers from Bangladesh should focus on forming and leading a coalition of soon-to-graduate LDCs to push for a new set of support measures to meet the demand for countries in transition (especially in the context of currently prevailing geopolitical turmoil).

Finally, looking beyond 2026, Bangladesh's economic diplomacy should focus on expediting negotiations with the WTO related to new/emerging sectors such as fisheries subsidies, e-commerce, investment facilitation, and promoting MSMEs.

Along with economic diplomacy, Bangladesh must prioritize domestic preparedness for smooth and sustainable graduation. The country needs to diversify its export basket (over 80 percent from one sector- RMG) and diversify its export destinations (an overwhelming share of exports going to 9 to 10 countries only). Structural transformation of the export sector will also be pivotal as 93 percent of Bangladesh's exporters are low-tech manufacturers (the ratio is 33 and 21 for Vietnam and India, respectively). While Bangladesh has made excellent strives to develop hard infrastructure, this trend needs further bolstering. A Bangladesh exporter still requires 28 days to complete an export process, whereas the average for Asia is 18 days. Private sector investment in infrastructure development must grow significantly (currently, private sector participation is only 1.1 percent of GDP). To reduce reliance on international development support/assistance, Bangladesh must also significantly improve its capacity to mobilize revenue domestically. Tax-GDP ratio for Bangladesh has been hovering below 10 percent for many years now, whereas an economy of such size and potential should have a ratio over 15 percent. This calls for fast digitization of resource mobilization and improving the governance of revenue management. Also, special attention is needed to ease the tax administration to attract more foreign direct investors.

In conclusion, it may be safely said that Bangladesh, with its extraordinary resilience and entrepreneurial zeal, has done very well in laying the foundation for a vibrant, developing country. However, the challenges remain, particularly in skilling and reskilling human resources to make the production process more efficient. In addition, the geopolitical challenges, including the latest tension in the Red Sea on the movement of ships and the threat of deglobalization or truncated trade cooperation, may constrain the potential gains from the graduation. The country may have to focus more on regional and subregional economic cooperation and greater emphasis on domestic production. The financial sector will have to reorient itself with more cooperation in the regional payment system to cope with the new landscape of trade cooperation in the new context.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments