‘The day begins wrong’: Mastering tension and suspense in fiction

In my creative writing classes, whether at the University of Toronto or the Hermitage Residency in Bangladesh, I emphasise that any student of fiction must first master suspense. Suspense is the lifeblood of fiction, whether a literary novel or the latest airport bookshop page turner, a state in which the audience (in this case the reader) is neither landed nor flying, but awaiting information. This information is being withheld from them by the writer, and the implication is that this information is important enough, of stakes that are high enough, to be worth the while of the reader to keep turning the pages.

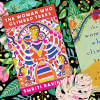

Suspense therefore defines the state of mind for the reader. What then is 'tension'? Tension is the story state that generates suspense. Often, this state of tension is established at the beginning. Take for example the opening lines of Atlas of Unknowns (Random House, 2009) by Tania James:

"The day begins wrong. Melvin feels it upon waking, as though he has slipped his right foot into his left shoe and must shuffle along with a wrong-footed feeling all day. That today is Christmas Eve brings no comfort at all."

Here tension is established right away. The very first line is a premonition of things to come, likely something unexpected, or even unpleasant that might happen to Melvin. Neither the character, nor the reader has any idea what it is (or perhaps he does, and has kept it hidden even from himself: "a knowing so deep it's like a secret', as Toni Morrison puts it). The writer has created tension, the reader is in suspense, and we all want to keep turning the pages to find out.

In the opening lines of Kazuo Ishiguro's The Remains of the Day (Faber and Faber, 1989), the tension is of another kind:

"It seems increasingly likely that I really will undertake the expedition that has been preoccupying my imagination now for some days. An expedition, I should say, which I will undertake alone, in the comfort of Mr. Farraday's Ford; an expedition which, as I foresee it, will take me through much of the finest countryside of England to the West Country, and may keep me away from Darlington Hall for as much as five or six days."

Unlike with Melvin in Atlas of Unknowns, tension is established as the protagonist here is (partially) sharing information known to them but not known to the reader. The reader is in a state of suspense awaiting resolution to a number of intriguing questions: Who is speaking? What kind of work do they do? Who is Mr. Farraday, and where is Darlington Hall? From their manner of speech the reader can formulate some assumption about the narrator, such as that they seem, if not a little uptight, then perhaps hidebound. That this is a person clearly attached to their job, that taking a holiday is something unusual for them, and that they hold Mr. Farraday in high esteem. These are all assumptions the reader might make as they read these lines, but they want to find out for sure. They want to know more. They are, in other words, in a state of suspense.

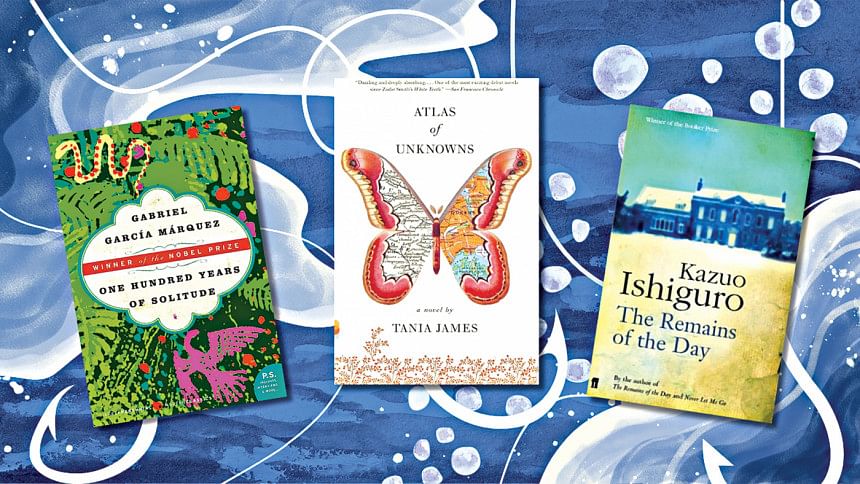

As a final example, take the iconic first lines of One Hundred Years of Solitude (Perennial Classics, 1998) by Gabriel García Márquez:

"Many years later, as he faced the firing squad, Colonel Aureliano Buendía was to remember that distant afternoon when his father took him to discover ice."

Here the reader is privy to a future event, one that the protagonist himself is unaware of. Even though we will ostensibly begin with Aureliano Buendía's childhood, we have been given a peek into his future, his inevitable end. The author has foreshadowed his death, has shared a secret with us, and we are thrilled by it. We want to know everything that lies between Aureliano's childhood and death.

The above examples illustrate how writers create tension on the page, and therefore suspense in the reader by selectively and strategically withholding information, either from the character, from the reader, or both. Of course, for this strategy to be effective, the information has to be of enough interest and intrigue for the reader to keep them engaged, and of high enough stakes for the character for it to be meaningful to them when it is inevitably revealed. No one, for example, would be interested in the resolution of what brand of toothpaste someone will buy (unless it somehow figures strongly in the plot). However, most people would be interested to know what a private detective has uncovered about the shadowy past of a new paramour.

Once a writer masters tension, they will generate suspense and keep the reader turning the pages. This thread of unease can be likened to a fishing line, sometimes slack, sometimes taut, but always present, and running the breadth of a reader's engaged interest, its weighted hook sinking deep into the recesses of their imagination, awaiting the bite.

Arif Anwar's debut novel, The Storm, was published by Simon and Schuster in 2018 to international acclaim and has been translated to multiple languages. Arif's work has been published in The Daily Beast, The Millions, Vice Magazine, Electric Literature and The Daily Star, among others. He teaches Creative Writing at The University of Toronto.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments