The Blue or Indigo Mutiny of 1861, was an outpouring of anger by Indian peasants coerced into cultivating the unprofitable indigo crop by British planters. It spread quickly in Bakarganj (present day Barishal), Murshidabad, Pabna, Khulna and Narail. The cultural and political consequences of the Indigo Mutiny left indelible marks on Bengal's colonial history. The most important fallout was widespread outrage at the cruelty of the white planters against the poor Indian peasants. As a result, the Nilkar became a byword for nightmares to many Bengalis. The planter class in Bengal struck back with intensified repression, and also used legal means to suppress any dissent.

The Bengali Christian converts, even when they were not a member of the elite urban intelligentsia, still created disruptions to the entrenched world-view of the British administrators and the non-official white planters.

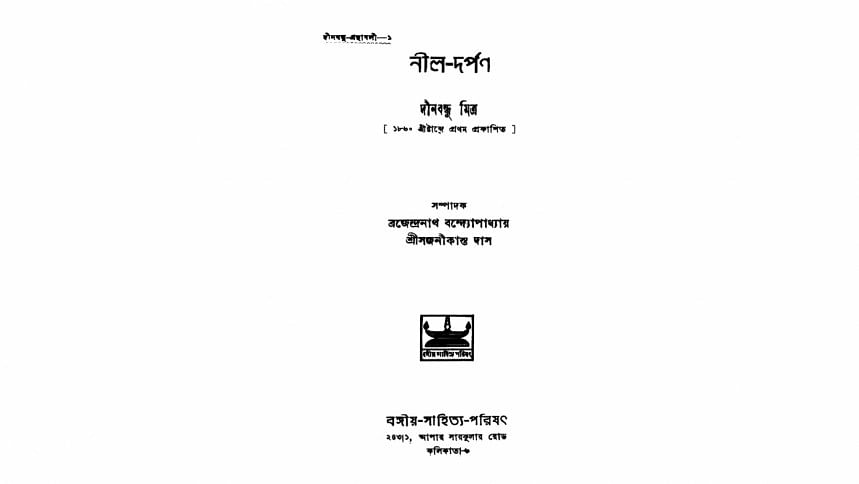

But there was another entity entangled in this tussle between the Nilkar and the peasant – this was the Christian missionary or Padri. The missionary's role as a disruptor of the relationship between the planter and the peasant requires more nuanced attention. As Dinabandhu Mitra's famous play, the Nil Darpan, had poignantly pointed out, the Bengali peasants, those from the depressed classes, and especially those that had converted to Christianity, suffered most in this tussle of interests between the planters, the missionaries, the high-caste Indian landlords and the British administrators:

Jaate malle Padri dhore/ Your caste is robbed by the Missionaries,

Bhaate malle Nil Bandore/ Your rice is robbed by the Indigo monkeys (Indigo planters)!

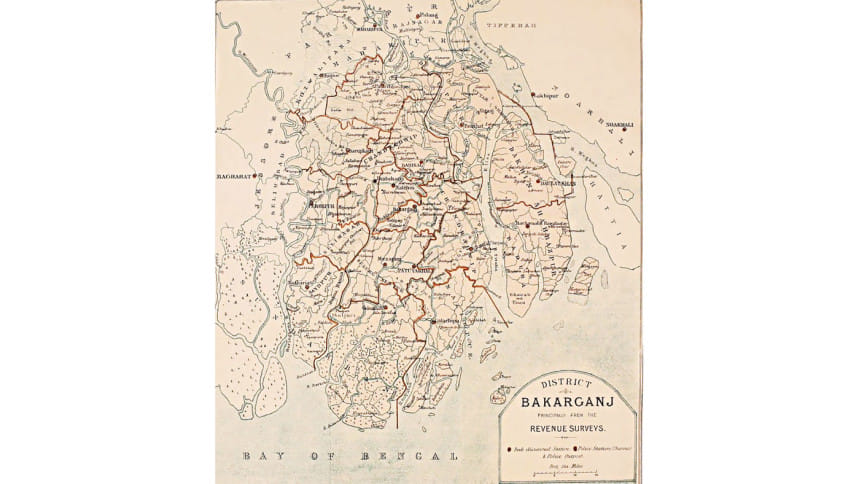

By 1855, of the two and half million inhabitants of Bakarganj, barely 6500 were Christians and the majority of them, close to 4000, were Baptist Protestants, largely due to the outreach efforts of the Serampore Baptist Mission. By the District Gazetteer Henry Beveridge's estimate, there were more Indian Christian converts in Bakarganj than in any other district in the Bengal Province, except Nadia and the 24 Parganas. The converts were mostly from the Chandal and Namasudra communities – avarna or untouchable in the caste-based hierarchies, now known as Dalits. In many parts of Bengal, including Barisal, it was the Chandals and the Namashudras who bore the brunt of violence at the hands of the planters.

When they converted to Christianity, hoping for upward social mobility and a mitigation of their suffering, they often had their hopes dashed since their conversion complicated their relationship with their landlords. Certain other facts about these converts often led to a head-on clash with the planters and zamindars. Converts were often better educated, through the pedagogical efforts of evangelical missions, than their Hindu or Muslim counterparts. Consequently, they were more aware of legal remedies and ways to enforce the power of legal relief in case of distraint under the haftam laws, regularly used by landlords and planters to dispossess tenants of rightfully held leases. Christian converts also usually refused to pay the customary taxes and gifts, called abwabs, demanded for religious festivals, births, deaths and marriages in the home of Hindu zamindars, and costs related to the functioning of the cutcherry and payment of gifts to police officials and native administrators allied to white planters. The intercession of the missionary created a counterpoint to the planter's previously undisputed reign. They created, perhaps unintendedly, power contests where none had existed before the arrival of the missionary and the conversion of the peasants and consequently violence broke out repeatedly.

One such case of planter violence against Christian converts happened in the Baropakhya village in Bakarganj. Christian peasants were dispossessed of their land violently at Baropakhya by the English planter and his Hindu officials. The relationship between the Hindu and Muslim inhabitants of Bakarganj with that of their lower caste neighbors was already one of deep tension and violent repression. When these neighbors converted to Christianity and became more vocal about their rights, supported by the white missionaries, the situation became intolerable for their high-caste neighbors, and their white planter landlords. Christian converts upset long standing caste-based hierarchical relations in Barisal, their presence caused constant tension regarding land ownership, and evangelical efforts on their behalf were perceived as deeply threatening to settled way of life in the region. J.C. Jack, former settlement officer of Bakarganj, commented that the conversions in Gaurnadi and neighboring areas, such as Baropakhya, had occurred "largely in a spirit of revolt against caste-bondage and zamindari oppression."

It was July in 1855, when the early torrential monsoon season had flooded rivers, tributaries and lakes and rendered significant parts of the southern tip of Gangetic delta in eastern Bengal impassable. Two missionaries of the Baptist Mission Society, Rev. J.C. Page and Rev. Robinson, received notice that the Christian converts at Baropakhya had been assaulted violently, their houses plundered and damaged, and some of them had been forcibly carried away. The organized attack had occurred on the night of 1st July 1855. Ledoo, a wealthy peasant, received the worst of the attack. He was beaten badly, his hands were tied with ropes, and he was stripped naked and made to stand and witness the assault on his friends and family. His pregnant wife Roso was dragged out of the house, her gold nose-ring and silver necklace snatched from her, and she was kicked to the ground twice while she tried to resist. She too was then stripped naked and assaulted in front of her husband and neighbors, then bound hand and foot and made to stand nude and witness the mayhem. The attack on the house of the other Christian converts were just as ferocious. Janoo, his wife Gouri and their four-year old son Hridoy had been asleep on the floor when a sarki (javelin) struck through the mat-and-mud wall, and pierced the baby on his arm. His wails awakened his parents, and when Janoo took the boy in his arms to shield him from the sarki thrusts, he was hit in the hand as well. By the time he had transferred his wounded and crying son to his wife, the walls of his hut had broken down under the assault. Janoo was thrown to the floor, stretched out, and beaten black and blue with a stick. The attackers also pierced the heel of his left foot with a sarki, hobbling him, so he could not escape. Gouri, his wife, and Ledee, his sister-in-law, were then assaulted before his eyes, stripped naked and bound, as was the baby Hridoy. Ramakrishna and his two brothers Nobo and Harakrishna were beaten, as was their mother Monee and grandmother Malancha, and bound with ropes. All the houses were plundered, the cattle lead away, brass and stone plate seized, and the stored granaries emptied out.

The treatment of the women at the hands of Brown and Munshi's lathiyals is couched by contemporary chroniclers in careful terms. One of them says, for example:

Mr. Brown and Mohan Munshi began persecuting the Christians and gave them unspeakable dishonor and distress…they behaved in such base manner towards the Christians at this time that it would be shameful to even bring it to one's lips.

The detail that stands out starkly in the reports is this - the women had all been stripped naked, assaulted violently in front of family and friends, and then bound and made to witness the torture of their kin. And while there are details of the wounds suffered by the men in the assault, there is a stark silence regarding the wounds that the women might have suffered – as if there was not any language available to describe their trauma. This lacuna, this silence, hints at terrible sexual violence. The historian Elizabeth Kolsky, for example, has analyzed the multiple ways in which rape could be discussed within the social and legal constraints specific to colonial South Asia. She demonstrates that the use of the terms "assault" and "carried away" were ubiquitous in colonial judicial records documenting cases of sexual violence. The ambiguity and silence around what had happened to the women was maintained even in court testimonies, presumably to allow for the barest cover of honor for these survivors of gangrape.

The terrible truth was this - on that dark monsoon night, not only were the Christian converts of Baropakhya assaulted and kidnapped, but their women were also subjected to sexual assault and rape in front of the male members of their families. They were violated by the trained militia of a white Christian British planter and his associates, stripped literally and figuratively of their dignity and their sense of safety, just as their male relatives were tortured and deprived of their possession of land. This kind of spectacular public brutality was and still remains in South Asia as one of the ways in which an entire minority community can be shorn of social standing and honor and intimidated.

While being questioned by the magistrate, between 9th August and 13th October 1855, the converts were all asked variations on one question – "What is the reason of committing this outrage upon you?" The answer invariably was, "They have committed the above outrage on account of our embracing the Christian religion." This clear articulation of the modus operandi behind the violent outrages perpetrated against them leaves no doubt that the converts were certain that they were tortured and deprived of their rightful possession of their lands and goods because of their change of religion.

Outrages against Christian converts continued in Nadia, Jessore and Bakarganj, especially in and around Barisal for the next many years, and judicial redress was always uncertain. On complaint by some Christian converts in areas neighboring Baropakhya, the deputy magistrate of Khulna, a fiery young man, named Bankim Chandra Chatterjee, was sent to investigate the repressions. He found that the converts were being harassed by planters as well as the zamindars of Kotalipara, and censured them. However, the oppression of Christians continued in Bakarganj for many years thereafter.

The role of missionaries in facilitating conversions of the peasants in Bengal, created a complex relationship between them, the British administration, the white planter population, and the converted Indians. In many cases, access to the missionaries was seen by converts as a way to find counsel on non-religious issues such as land-proprietorship, which was the most important consideration for India's peasant population for their livelihood. The complex nature on plantation labor and the profoundly unequal relationship between the planters and the peasants involved in indigo cultivation in Bengal created both systemic and actual, tangible violence. Christian conversions then, remained not only in the realm of the theological, but had profound political, administrative, legal, and social repercussions. The British official and non-official population were suspicious of conversions among Indians precisely because they suspected that it would help the converts to bypass colonial hierarchies in collusion with missionaries. The missionaries of Baropakhya, and later the colonial officials like Charles Trevelyan argued that native-Christian converts became the subject of non-official white violence precisely because their conversion allowed them to evade the waiting-room of history altogether. The Bengali Christian converts, even when they were not a member of the elite urban intelligentsia, still created disruptions to the entrenched world-view of the British administrators and the non-official white planters.

Baropakhya proved conclusively that Indian converts would insuperably be condemned by the act of their conversion, to be socially, legally and politically disinherited.

Mou Banerjee is an Assistant Professor of History at the University of Wisconsin-Madison.

Comments