Only 10% of planned economic zones get off the ground in a decade

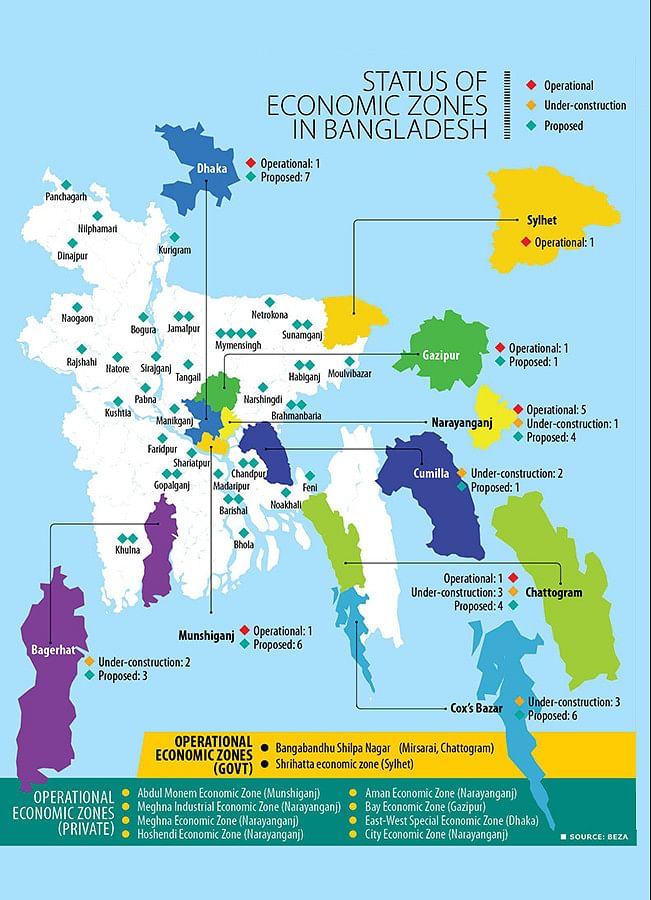

Only 10 economic zones (EZs) have become operational since the Bangladesh Economic Zones Authority (Beza) rolled out its massive industrialisation plan in 2015, raising questions about whether its goal of setting up 100 enclaves will be materialised on time.

The board of the Beza has approved a total of 97 EZs over the past decade. Of them, 68 zones will be set up by the government and 29 by the private sector, with the initial deadline set at 2030.

The deadline was later pushed back to 2041 since executing such a high number of projects will take a considerable amount of time in a country where time over-runs are commonplace and acquiring land is complex, which delays implementation.

Of the 10 economic zones, two are government-run -- Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujib Shilpa Nagar (BSMSN) in Chattogram, the Sreehatta Economic Zone in Sylhet -- and eight are private.

The private EZs are City Economic Zone, Meghna Industrial Economic Zone, Meghna Economic Zone, Hoshendi Economic Zone, Abdul Monem Economic Zone, Bay Economic Zone, Aman Economic Zone, and East West Economic Zone.

In the two state-run zones, 13 companies are already producing goods: 11 factories have been built in BSMSN and two units have been set up in Shreehatta, according to Beza documents.

Besides, infrastructure development work for 36 factories is underway at the government EZs. Among them, 25 will be set up at BSMSN, four in Shreehatta, five in Jamalpur, and two in the Japanese Economic Zone.

The Beza has so far given approval to 29 private EZs, with 12 enclaves granted final licences and 10 awarded pre-qualification certificates. Of the final licensees, eight have gone into operation.

A total of 17 factories are under construction in the private economic zones.

Shaikh Yusuf Harun, executive chairman of the Beza, does not think that there has been slow progress in implementing EZs.

"Ten zones are already operational, and the number will go up to 29 within the next two to three years."

He said the Beza has revised its target to set up 100 EZs by 2041 from 2030 initially since implementing an economic zone project takes time.

"We will be able to make at least 38 EZs operational by 2030."

Harun said they have been successful in generating a significant number of jobs, particularly in the manufacturing and service sectors.

Anwar Hossain, an economist at Development Design Consultants Limited, an engineering consulting firm, has been involved in providing feasibility consulting services to many government infrastructure and development projects.

He said the Beza has invested heavily in developing EZs nationwide, so it is time to operationalise them by establishing factories and recovering the investments.

"This is crucial for Beza's sustainability," he said, adding that the Beza has made important strides in attracting foreign investments and producing goods for international markets over the last decade.

Anwar Ul Alam Chowdhury Parvez, president of the Bangladesh Chamber of Industries, said the authorities should develop the sites first before offering plots to investors.

"Otherwise, if investors go there, they will suffer because of a lack of necessary infrastructure in the zones."

The entrepreneur alleged that the investors who have obtained plots in the zones are yet to get utility connections and they are even ensuring water supply on their own.

Syed Akhtar Mahmood, a former lead private sector specialist at the World Bank Group, praised the idea of EZs as effective since there is land scarcity in Bangladesh and the country is looking for well-planned industrialisation.

He suggested providing land only to investors who have good intentions of setting up factories. "Otherwise, genuine investors will not get the land when they need it."

Mahmood said the Beza should implement EZs in phases instead of going after all of them simultaneously.

"This is because if all EZs are implemented concurrently, none of them will be executed properly since there is an involvement of a huge amount of funds."

M Masrur Reaz, chairman of the Policy Exchange Bangladesh, a think-tank, said delay is usually seen when an EZ moves to the operational stage following the identification of a site given the nature of the project.

"Land acquisition is critical as it is scarce in the country. This delays the implementation of the projects."

The former economist of the International Finance Corporation said the Beza has gained experience in the last one decade and knows about the opportunities and bottlenecks.

"There will not be much delay if the Beza puts the experience to good use when implementing the projects."

The Beza has received $28.75 billion worth of investment proposals from companies at home and abroad. The actual investment stood at $6.05 billion between 2020 and June 30 last year.

According to a report of the agency, the operating zones have employed around 60,000 people. Some 7,000 are working in government-owned zones and 53,000 in private zones.

Products worth $14.47 billion were produced in 10 EZs in the last fiscal year of 2022-23, it said.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments