A post-election defining moment

The finance minister and his team must have trotted slippery slopes as they formulated the about-to-be-announced FY25 budget. The slopes are slippery because of the extraordinary economic compulsions on the one hand and the expectations of re-election friendly forces on the other. Ignoring either of the two imperils life in government.

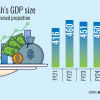

The economy has been in a rough patch since 2022 like never before in the past decade and a half. Growth slowed, inflation surged, real wages fell, foreign exchange reserves dwindled, financial sector stressed, private investments stagnated, and the external environment did not help. The budget cannot solve it all but, being the first after election, it constitutes a defining moment to signal a resolute commitment to put the economy back on a stable and growing trajectory.

The government has turned to the development partners for cash support to stay afloat in troubled waters a large part of which owes to failure to respond in time. Support is obviously not a freebee. You have to commit to measures that have the promise of addressing the underlying causes. The urgency of doing so can hardly be overstated.

The measures include bold decisions to keep the budget deficit low enough to relieve pressure on prices and foreign exchange reserves; plug revenue draining holes in tax policy; rationalise public expenditures by curtailing failed subsidies and development projects; and roll out structural reforms to relieve financial distress, resuscitate structural transformation, and face the music after LDC graduation.

None of these can be done without risking displeasure of the sources of political power of the current regime.

They have already voiced their concerns in no uncertain terms even while recognising the economic compulsions. They say tax expenditures are a problem, but this is not the time shunning them; increasing taxes on carbonated beverage manufactures can be good for both the government purse and public health, but this would reduce investments; taxing capital gains is desirable for enhancing progressivity of the tax system, but the stock market is not ready for it; export subsidies have not produced the desired results, but this means you have to do more rather than less until WTO rules kick in; cutting public spending may be necessary, but it will hurt "people"; spending more on education and health is critical, but this must not be at the expense of prolific contracts in transport and energy and so on and so forth.

An iron law of protection to business is that it tends to become a necessity. A specific interesting case in point is duties on imported mobile phones. Local mobile manufacturers have benefited from tax exemptions and lately the large devaluation of taka which has made imported phones more expensive. Yet they complain devaluation has put financial pressure on them without bestowing any competitive advantage! They want continuation of the existing taxes on imported phones for another three years.

Yet another case is export subsidy. The government's cash incentive against export receipts has soared over the years although it brought limited, if any, results in export diversification. Currently, 43 sectors receive cash support, which amounted to over Tk 8,600 crore in FY23 alone. These cannot be continued after 2026 as WTO rules do not allow cash incentives to exporters.

The government cut the subsidy for almost all sectors in February reducing the highest cash incentive rate from 20 to 15 percent. The export lobby raised concerns about hurting small and medium enterprises and power tariff hikes to oppose the subsidy cuts.

Never mind the 26 percent depreciation of taka since end-June, 2022 which enhanced revenues way more than costs.

It is not just the interest groups outside the government who exhibit cognitive dissonance by supporting change while opposing it at the same time. Government officials at the upper echelons have been living a "don't worry, be happy" delusion ever since the onset of economic distress. They continue to harbor the belief that things will turn around by "December", one that never came in last two years.

Policymakers have evidently found it difficult to invest the time and political capital to address a crisis that was never abstract.

The policy response has continued to be tempered by political realities. Business interests have pressed for subsidies and bailouts on grounds of times difficult for all even though many benefited from the same difficult times.

Policymakers diverted resources away from developmental priorities under pressure from these constituents. As the saying goes, "where you stand depends on where you sit."

Some members of the public, and some policymakers, have resisted the recommendations of experts until they came with money from the IMF.

Every government faces tough decisions about the appropriate measures: how much to tighten, when, for whom to loosen policies, where money will be spent and how it will be raised. These decisions have to consider economic and political fallouts. Any policy that is good for society as a whole can in principle be made good for everyone in society by taxing the winners just a bit to compensate the losers.

The problem is that the winners don't like sharing any of the wins. The battle is rarely over what is best for society but rather over who will be the winners and losers. What is best for the country may not be best for my district, or coterie, or industry, or class.

The golden rule of policy is that those with the gold make the rules. Bangladesh is no exception. Special-interest groups play an outsized role. Concentrated interests win over diffuse interests.

Will this budget be different? One can still hope because even authoritarian regimes have to pay attention to at least some part of public opinion. They are called the "selectorate," that portion of the stakeholders, local or otherwise, whose support matters to policymakers to stay in office and to the elites to keep their seats.

We will find out which selectorate have mattered in this budget!

The writer is former lead economist of the World Bank's Dhaka office.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments