The Santal Hul: Arrows against muskets

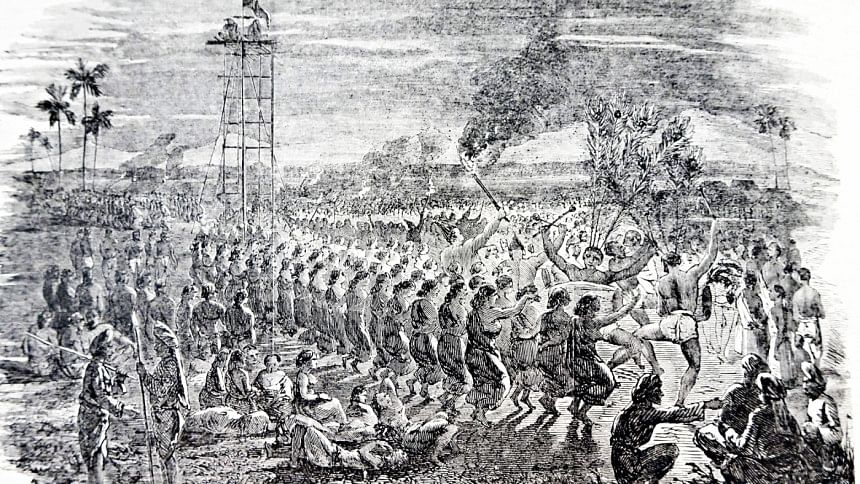

Exactly 169 years ago, in the jungles of what is now the Indian state of Jharkhand, Bengal Army sepoys fired the final shots in what became known as the 'Hul', or uprising, of 1855. The last of about two thousand Santal fighters died in the Hul's last, anonymous clashes. For six months Santal bands had roamed the jungles of Bengal, burning, plundering and murdering those who had oppressed them. The Hul remains the central event in the recorded history of the Santal people of India and Bangladesh, the subject of songs, poems and stories – and later novels and even films, a heroic episode more celebrated than analysed.

Though of great importance to the Santals, the Hul has been the subject of just a handful of books, though many anthropologists refer to it in explaining how Santal culture has evolved, especially in relation to the nations of which they are a part, of India and Bangladesh. In 2022, my own book on the uprising appeared – Hul! Hul!: the Suppression of the Santal Uprising, Bengal 1855, published in India by Bloomsbury: its first military history. I tried to explain the failure of the Hul by drawing upon an historical source never before used by its historians – the vast and detailed records of the Bengal Army.

I consulted the existing sources (including precious Santal accounts of the Hul), visited some of the sites where the Hul occurred and especially read the huge number of detailed accounts of the rising as it is revealed in unpublished British records. That gave me a new and challenging view of it. Was I merely repeating British accounts? I don't think so: read on.

But what right, you might ask, did I, an Australian historian, have to write about an event of such importance to Santal people – especially when I have not a word of Santali? I must admit that my research might seem to be surprising; even offensive. I can only reply that I think that the Hul deserves to be accorded the respect of being treated like the major conflict it clearly was. The Hul was and remains important to Santals, and Santal authors should be writing about the Hul, drawing upon the communal and cultural sources only they can obtain. I offer a perspective that can only help to illuminate Santal historical experience.

But the Hul was and is not just important to Santals alone. It was an event of importance in India's colonial history. The rebellion which consumed the Santal country in 1855 was (after the great mutiny-rebellion of 1857) the single largest rebellion faced by British India's rulers until the great independence movement began in the late nineteenth century.

In describing the Hul, many authors quote Vincent Jervis, a British officer of the Bengal Army, who famously described an incident in the suppression of the rising as 'not war … it was execution'. The incident he was describing, when sepoys of the 56th Bengal Native Infantry trapped a party of Santals in a house in Narainpore (now Narayanpur, West Bengal), was a matter of simply killing men who simply would not surrender. But should Jervis's description be applied to the Hul as a whole? Was the suppression of the Hul merely a matter of 'execution'? The more I read the British records, the more I saw the Hul as an insurgency fought by both sides.

The Santals, I realised, should not be seen merely as the victims of British repression. They rose in rebellion in the monsoon of 1855, finally unable to stand the oppression of the landlords, merchants and moneylenders who oppressed them (most of whom were Bengalis). They rebelled not so much against the rule of the East India Company (though they were disillusioned at how poorly its officials protected them from exploitation) but it was the forces of the East India Company's Bengal Army which acted swiftly, efficiently and often brutally to suppress the uprising. Indeed, more than a tenth of the entire infantry strength of the Bengal Native Infantry was deployed against the Santal Hul: this was a major challenge to the stability of British India.

The Hul began late in June 1855 in the Rajmahal Hills. The hot weather had rumours circulated, reports of supernatural portents of a coming apocalypse. No one anticipated the scale of the spontaneous outbreak of rebellion (certainly not the district's British officials, who had no idea of Santal grievances). It began with the killing of a darogah – a police official – who had been notable for his cruelty against Santals. The killing sparked a mass movement, in which thousands of Santals joined.

The Hul was and is not just important to Santals alone. It was an event of importance in India's colonial history. The rebellion which consumed the Santal country in 1855 was (after the great mutiny-rebellion of 1857) the single largest rebellion faced by British India's rulers until the great independence movement began in the late nineteenth century.

Columns of Santals moved out of the Rajmahal hills, killing the merchants, zamindars and petty rajahs who had oppressed them. Reports of atrocities they committed – a measure of their desperation and despair – reached the British authorities, who reacted swiftly. Within a week, sepoy regiments began marching toward the disturbed region.

At first, the Santals experienced military success. At Peer Pointee, just south of the Ganges, on 16 July, they routed a force of Hill Rangers sent from Bagulpur. Inspired by the charismatic brothers of Bugnadihee (today Bugnadee, Jharkhand), especially the Santal heroes Sidhu and Kanhu, they believed that sepoys' musket balls would turn to water. Some British officials panicked and refugees, British and Bengali, fled from the approaching Santal bands. For several months a huge swathe of Bengal, from Bagalpur in Birhar to Suri in West Bengal, and east to the Bagiruti River, was out of British control.

Soon, though, the Bengal Army exerted its power. The 7th Bengal Native Infantry marched from Berhampore and as early as 15 July attacked a large Santal force at Moheshpore (now Mahespur, Jharkhand). Sepoys arrived on elephants (provided by the Nawab of Morshedabad, anxious for his security) and met Santal charges with musket volleys, a fight in which perhaps 200 Santals died. In that battle three of the Bhugnadihee brothers were wounded, bravely leading their followers. Sepoy columns advanced into the Santal country from Suri in the south, Bagalpur in the north and from Berhampore to the east. While for a month or so the two clashed almost accidentally, each side then developed a sort of strategy.

Lacking coherent leadership, the Santal bands roamed around the region, looting and living off villages, driving off tens of thousands of refugees, many Bengalis. Gradually, they moved towards the south-west, seeking to cross the Grand Trunk Road towards their ancestral lands in Chota Nagpore. When British movements frustrated this impulse, diehard Santals gathered in rugged jungle-clad hills on the borders of what were then Bhagalpur and Beerbhoom districts, holding out even as they suffered from starvation and disease.

After initial indecision and even panic, the British strategy blocked Santal movements by holding chains of military posts, combined with aggressive forays (which they called 'dours') under energetic younger officers, and then in November and December declared martial law and launched a concerted 'drive' to destroy and disperse the last Santal bands.

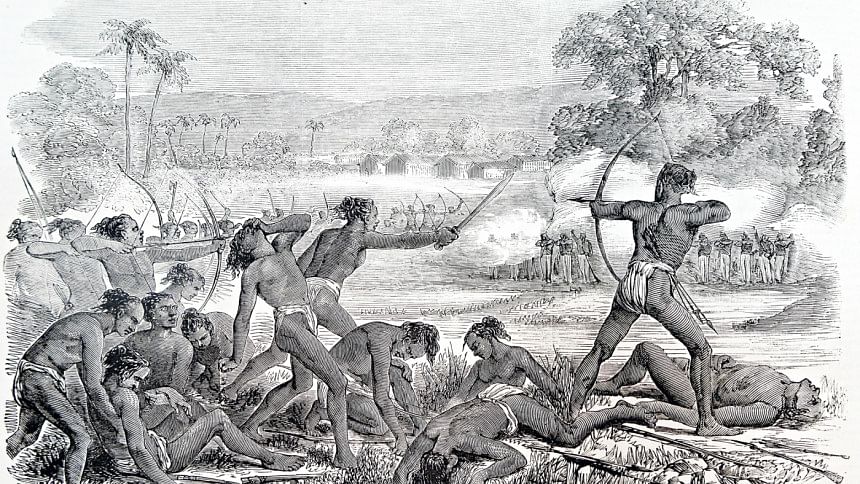

The Hul saw many fights between small sepoy forces and large Santal bands, the names of which have usually never been published in English sources, though Santal songs and stories may record them. These included the six-day Santal siege of the post at Koomerabad (Kumrabad, now covered by the waters of a dam on the Mayurakshi River), and the fight at Bissohuwa, somewhere in eastern Jharkhand. There, on 1 August the two sides clashed, at a place I could not identify, but the fight was described by the British officers, and drawn by a surveyor accompanying the force. The officer wrote of Santals who 'arose as if by magic', charging the sepoys even as they fired volleys at them. Many other skirmishes occurred at nameless places. Though often the only accounts of them were written by the British officers – never before published – they give valuable insights into the Santals' experience of rebellion, including making clear why so many risked so much for their communities.

The Santals acted out of desperation, hampered by many serious shortcomings: they had no warrior tradition or military organisation or political program; their only arms were hunting weapons – bows and arrows. Crucially, they had no accepted commanders, besides the four brothers of Bhugnadihee, whose charismatic leadership inspired the outbreak of the Hul but proved unable to control it.

While the Hul failed largely because the Santal bands abandoned their villages and fields and increasingly suffered from disease and starvation in huge, improvised jungle camps, Santals learned how to fight an insurgency as they went. They used their assets well – they knew their own country and were able to move more swiftly than the slow-moving sepoy columns, moving at the speed of their elephant transport. While at first trusting in sorcery, Santal leaders learned how to direct their bands to stand and fight, even using bows and arrows against musket volleys. They learned the tactics of jungle insurgency: these brave men were not simply the victims of 'execution'.

The Bengal Army 'Field Forces' which responded to the Hul also learned. Sepoys learned how to move and live in the jungle, adopting 'light infantry' tactics, search-and-destroy patrols, bringing in cavalry and even using rockets in pursuing Santal bands. They used river steamers and Bengal's first railway to move troops, supplies and intelligence around the region. British records show that they saw the Santals as an enemy whose courage they came to respect. A British civilian who witnessed Santals attacking wrote admiringly that they 'never dodged but stood' – even as he shot at them.

The Hul was a war, and a 'dirty' war at that. For every report of Santal 'savagery' – they took bloody revenge on those who had oppressed them – there was a report of the troops' 'severity'. Eventually, after the end of the monsoon, columns of sepoys conducted 'drives', advancing across the Santals' lands, breaking up their bands and killing or capturing those still resisting. By the end of 1855 the rebellion had been extinguished, at a cost of about 10,000 Santal lives, most dead of hunger and illness: many women and children.

Although the rebellion failed, it did bring change for the Santals. Recognising that a tribal people needed protection, the Company created the Santal Parganas, governed by British officials whose paternal care contrasted with the indifference that had provoked the Hul. They ruled through the very village leaders who had been instrumental in the Hul.

The Hul was largely forgotten by India's British rulers – they published almost nothing about it. But the Santals never forgot, creating a rich seam of songs, stories and poems about it. In due course, as India's freedom movement grew, Indian nationalist historians re-interpreted the Hul as a rebellion against British rule, one suppressed by 'British' troops. In fact, the Santals rebelled against the oppression of Bengalis, the Hull suppressed overwhelmingly by Indian troops – under British command.

Regardless of how it may be viewed, the Hul deserves to be better known, and not just among Santals. My book Hul! Hul! offers a new view of the Santal uprising, inevitably largely from the perspective of those who fought against it. But even the British records shed new light on the Santals' bravery, ingenuity and resolution in fighting to defend their interests as a people.

Prof. Peter Stanley of UNSW Canberra is one of Australia's most distinguished military historians.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments