The state has been captured by a select few

"What we classified at the time of Bangladesh's creation as an intermediate regime has become a fully-fledged capitalist regime fully captured by not just by the capitalists in general but by a segment of that particular class."

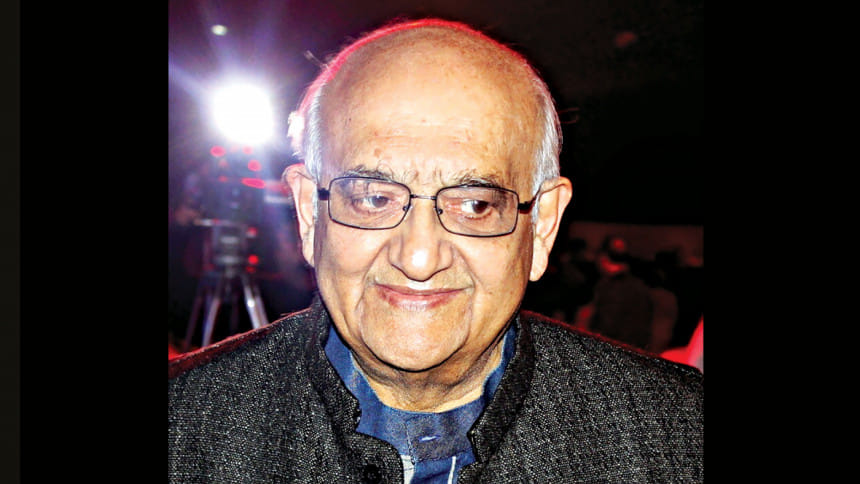

A class of people have evolved in Bangladesh who have not just captured the state but have become the state itself, said noted economist Rehman Sobhan.

"It is going to be very difficult to do anything about it because this class has now joined hands with the bureaucracy," he said at a seminar yesterday on "Political Economy of Banking Sector of Bangladesh".

The virtual event was organised by Samaj Gabeshana Kendra.

"What we classified at the time of Bangladesh's creation as an intermediate regime has become a fully-fledged capitalist regime fully captured by not just by the capitalists in general but by a segment of that particular class."

Sobhan, also the chairman of the Centre for Policy Dialogue, also touched upon the issue of effective interest rates.

If a loan is not repaid in 10 or 15 years, then the actual interest rate becomes much lower.

"The interest rate is widely unequal depending on whether you are actually repaying your loans."

The default culture has created a distortion in the setting of interest rates.

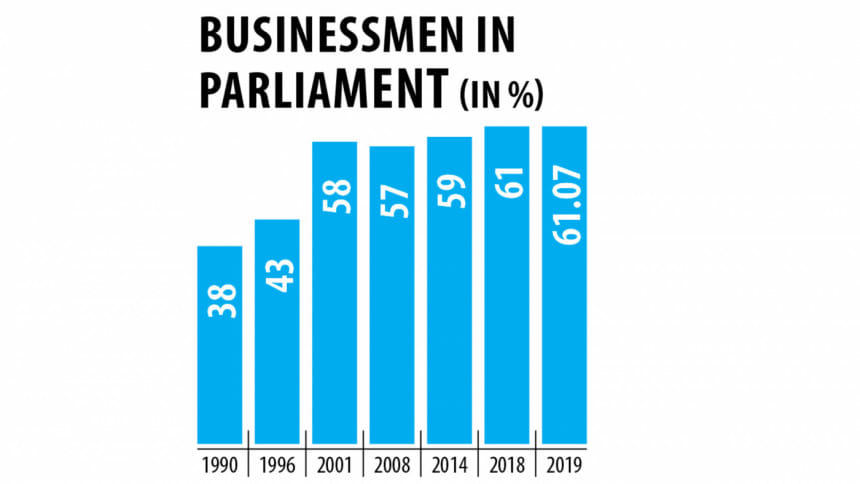

"Political patronage became the main criteria for lending. If you were lending to a politically patronised class that patronage would then become a political resource. And that political resource would then be used to ensure that your loans were not effectively collected. Once that happened, that class then became more empowered."

They then acquired political capabilities and political strength.

"And you then evolved from a fabricated capitalist class into a perfectly strong and well-established capitalist class that would move into exercising political power. Here, cronyism became a very important factor because whilst all capitalist classes are created dominant, some amongst them are more dominant than others and that was the nature of the problem," Sobhan added.

Bangladesh's banking sector is bearing the brunt of the political bias towards the wealthy and the influential, said Biru Paksha Paul, professor of economics at the State University of New York at Cortland.

"The banking sector is paying the price of political favouritism toward the superrich."

This started with the interest rate cap imposed in April 2020.

"The interest rate cap came into effect during the pandemic although it had no connection with Covid. The businessmen's hidden agenda was to get loans at effectively zero real interest rate and they made it happen."

The finance ministry tried to justify the cap in the name of private investment, which arguably did not show any sign of improvement following the adoption of the lending rate cap, as reflected in the private investment-GDP ratio, he said.

"It facilitated the tycoons to siphon off funds from banks at near-zero real interest rates," he said while presenting a paper on 'Bangladesh's Banking Sector: the interest rate cap, and govt's borrowing from the banking sector'.

The 9 percent interest rate cap made the real interest rate negative, and that outcome finally induced the partial dehydration of the financial account of the balance of payment.

The dehydration of the financial account aggravated the reserve crisis, contributed to the taka's free fall, enforced import controls and finally brought down GDP growth.

The depreciation of the taka made imports expensive, which fuelled the fire of inflation further, said Paul, also the former chief economist of the Bangladesh Bank.

The dwindling tax-GDP ratio and the ambitious development expenditure narrowed the government's capacity to finance the budget deficit.

As a result, the government resorted to desperately using banks' money, limiting the capacity of banks to lend as per the growing demand for credit.

However, the government's borrowing from banks kept rising due to growing fiscal incapacity and the political philosophy of not creating pressure on the wealthy elites for direct taxes, he said.

In fiscal 2022-23, the government borrowed Tk 1.25 lakh crore from the banking sector. Of the amount, 79 percent was borrowed directly from the BB.

As much as Tk 1 lakh crore of high-powered money was injected and that is to blame for the stubbornly high inflation, Paul said. The high-powered money saw a multiplier of 4.93 last fiscal year.

Since it was not taken from commercial banks, it fuelled monetary expansion instead of soaking up banks' liquidity.

"The country never saw such irresponsible borrowing before this."

Overall, the lack of timely monetary tightening by raising policy rates and the utter absence of fiscal tightening via raising taxes on the wealthy and curtailing public spending jointly fuelled the flames of inflation, Paul added.

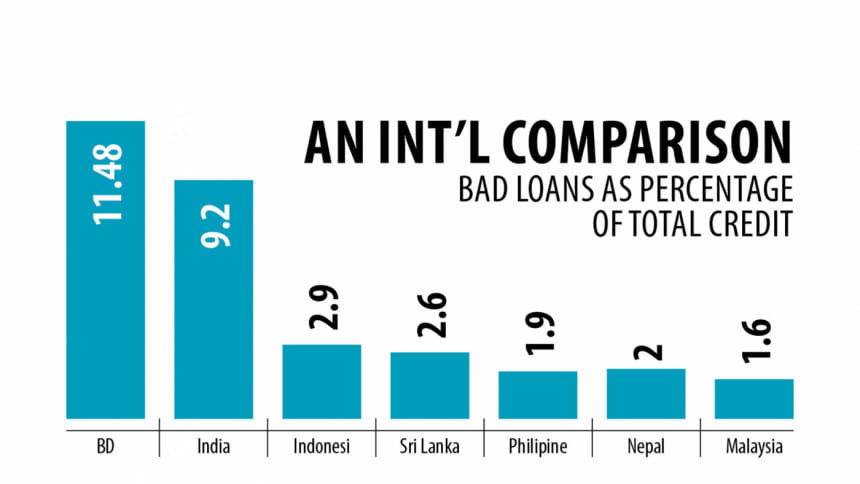

The volume of defaulted loans amounts to a staggering 11.48 percent of total credit, said MM Akash, professor of economics at the University of Dhaka. This does not include the written-off loans.

As of March, total defaulted loans stood at Tk 182,000 crore.

"However, the real situation is far graver. If we include rescheduled and written-off loans to this, the de facto aggregate default loan amounts to more than Tk 400,000 crore."

However, hiding the true defaulted loan figure is politically convenient.

"The nexus of dishonest businessmen, bureaucrats and politicians have captured the state bodies and all institutions that could make the bad loan issue transparent and accountable."

Some shariah-based banks are ailing due to their owners but the central bank wanted to save those banks by providing liquidity support.

"This is not wise. Why did the government want to bail out the banks? Their owners are liable for their ailing financial health."

Akash suggested making the post of the central bank governor a constitutional post. At present, the finance ministry appoints the governor.

"There is a dual regulator for the banking sector -- the finance ministry's control on banks will have to be stopped."

The top 100 loans defaulters' list must be published to build public awareness against defaulters, said Akash, also the chairman of Dhaka University's Bureau of Economic Research.

The independence of the central bank is needed, said Selim Raihan, executive director of the South Asian Network on Economic Modelling (SANEM).

"But the question is are the political elites willing to give the freedom? The political elites don't want to."

When talking about the interest rate cap, he said that not everyone benefited from the single-digit lending rate; only a certain segment benefited from it and a portion of the loan was laundered, he added.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments