The nine lives of a corrupt public servant

Cometh the hour, cometh Obaidul Quader. Part of the charm of Awami League's long-running general secretary is that he always seems to deliver the most memorable lines about his opponents, even if they aren't entirely original. So recently, after a barrage of high-profile scandals rocked the administration, he set out to outline the government's strategy to curb corruption, using a reference that would seem strange to many: khela hobe. Yes, that all's-fair-in-love-and-war inspired mantra that guided Awami League's ruthless campaign against its rivals prior to the 2024 election.

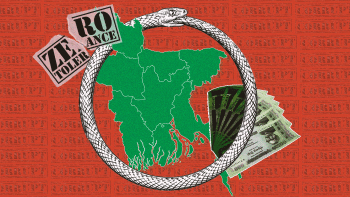

"The game is again on [Abaro khela hobe]," Quader declared in front of a party gathering. "It's on against corruption, plundering, and money laundering." This is not the first time that he used a sporting reference to take on corruption, addressing it as if it were an actual rival. The question is: how does his administration plan to play this game? Will it be like how it played last time, through force and coercion? Or does it have any special plan we are not privy to yet? Details are scarce at this point. So far, beyond rote reiterations of its "zero tolerance" commitment, occasional disciplinary spectacles that hardly qualify as punishment, and lengthy proceedings that may kick the judicial can down the road indefinitely, the administration has betrayed little awareness that it is no longer enough to go after a few rotten apples—it must go after the very system that enables corruption.

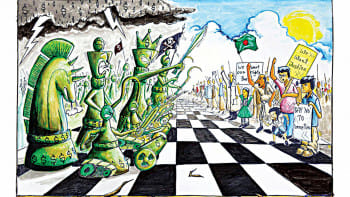

We can talk about how corruption has spread its tentacles in every sector, from banking to health to energy to transport to construction to civil aviation. We can talk about how nothing moves without bribery. But for a fuller grasp of how it all works and where it all originates from, we must examine civil service—the system governing public officials—which seems designed from start to finish to foster a partisan and corrupt bureaucracy. But since we are into references, let me use one that aptly portrays the seamless progression of public servants through this system: the cat with nine lives.

The general idea behind this myth is to celebrate cats' natural suppleness and swiftness allowing them to get out of potentially fatal situations. Now, think of the nine lives granted to cats as the nine or so lifelines or stages through which state officials are supported, sometimes starting even before recruitment and continuing well into retirement. Think of how they are favoured or shielded at every turn. And ask yourself if so many of them turning out to be corrupt or compromised is a coincidence.

Let's delve into these hypothetical lifelines in a public servant's career:

Corruption at pre-recruitment stage

The whole process of corruption in the civil service starts with the cultivation of the idea that government jobs are superior to all others. Power, prestige, money, and job security—nothing beats this lucrative offering, with the private sector proving to be a poor substitute. Hence the mad race for all recruitment tests held under public authorities. Hence the demand for leaked question papers and all those supplying them, even from within the PSC. Hence the metamorphosis of public universities into BCS factories, and their libraries into BCS workshops. Hence the debate on extending the age limit for government jobs to 35 years.

I can go on and on, but you get the message: that the unhealthy competition in civil service recruitment and the lack of private sector alternatives have created an atmosphere that breeds and feeds off desperation. This is where future officials get their first lesson: that corruption can give you an edge over the teeming thousands. So you see some candidates spending lakhs for that golden goose of a job. You see others leaning on the preferential quota system, or leaked question papers, or their political connections. You see Chhatra League leaders locking up university VCs, or the government—forever wary of dissent—delving into irrelevant details like candidates' political affiliations during post-exam background checks, thus further undermining meritocracy. How likely are those emerging from such a compromised process to respond to Obaidul Quader's plea to "play," and rein in corruption or refrain from corrupt practices themselves?

We can talk about how corruption has spread its tentacles in every sector, from banking to health to energy to transport to construction to civil aviation. We can talk about how nothing moves without bribery. But for a fuller grasp of how it all works and where it all originates from, we must examine civil service—the system governing public officials—which seems designed from start to finish to foster a partisan and corrupt bureaucracy.

Post-recruitment privileges and exemptions

There are about 14 lakh government employees spread across the public sector. Once recruited, employees receive lucrative salaries, allowances, and benefits, with a side dish of opportunities for corruption. It's no wonder why certain departments and postings are so highly sought after, or why so many medical and engineering graduates are lining up for BCS general cadre, forgoing once-cherished careers in specialised fields. State officials are granted powers and privileges, sometimes even undeserved promotions, that come with little scrutiny or accountability. Further relaxations of rules governing their activities are on the cards.

For example, the public administration ministry is reportedly set to allow public servants to engage in stock market trading, reversing a prohibition in the Government Servants (Conduct) Rules, 1979. If it comes to pass, they will be able to buy or sell shares legally. Why is this problematic? Recall that Matiur Rahman, a top NBR official now under investigation for corruption, allegedly made a fortune through stock market investments, using insider information, both of which are illegal. Many government employees are similarly engaged in stock trading and have demonstrated their willingness to exploit privileged access for financial gain. So, legalising it may open a Pandora's box of unethical practices. Or, think of the proposal to relax another provision in the service rules requiring officials to submit wealth statements every five years, removing an important layer of scrutiny that already stands significantly diluted.

Relaxed penalties for corruption

Those who are honest have nothing to fear from punishment. But when penalties are reduced by relaxing anti-graft rules, it benefits only the corrupt, and this is what the administration has done on a number of occasions. For example, in 2018, an amendment to the Government Servants (Discipline and Appeal) Rules (1985) introduced "reprimand" as a penalty for proven corruption, besides other penalties. You often hear of salary reduction, or "closing," or demotion, or transfer—so often the penalties of choice—which does feel like a slap on the wrist given the gravity of some of the crimes, thus further encouraging corruption.

Over the years, we have seen how such anti-graft regulations have been relaxed. In any sector other than public, the punishment for proven corruption would be instant termination. A recent editorial by this daily recounts three incidents where the accused, despite being found guilty of corruption, continue to be in service as they have been spared harsher departmental actions and even legal consequences. What message does it send to the wider public servant community? This policy of leniency provides a safety net for dishonest officials and contrasts sharply with the government's zero tolerance stance on corruption.

Lack of accountability for failures and inefficiencies

Another lifeline extended to government officials is through a collusive arrangement in which departments, and relevant officials, responsible for certain failures are seldom held accountable. You often see people die or suffer terribly because of accidents, disasters, and crimes that can be linked to the mismanagement, negligence or inefficiencies of certain government departments. Yet rarely, if ever, is a higher-up punished or even subjected to a reprimand. There is a tendency to let them off the hook during interdepartmental inquiries.

The case of a former deputy commissioner of Cox's Bazar, who reportedly got his name removed from a list of accused for misappropriation of funds with the help of several court officials, including a former judge, shows to what extent power can be abused to both commit crimes and protect criminals—both being the same person in this case. But he wasn't acting alone, neither do corrupt or compromised or inefficient officials, as they protect each other. And more often than not, the system allows it. We may recall how the attorney general himself told the apex court a few years ago that the parliament had passed the Government Service Act, 2018 to protect public servants, considering them a "different class of people." The same act had mandated law enforcers to seek "permission" for arresting public servants in criminal cases before the court, in August 2022, scrapped the relevant provision. But this culture of impunity has reached such a state that top officials are often seen directly flouting court directives, with no consequences faced.

Scandal-hit top officials, politicians, MPs, vice-chancellors or anyone like them rarely, if ever, resign in Bangladesh, even amid public protests. A common refrain among those under pressure to step down from their positions is that they will only do so if directed by the prime minister, indicating a culture where political loyalty supersedes accountability. Their connection and conviction further undermine what few accountability mechanisms we have left, however fragile.

Endless opportunities for corruption

The extent to which government officers and even low-level operatives can exploit their positions to engage in corruption, taking advantage of the protection and lack of oversight provided by the system, has again come to light following a series of financial scandals reported by the media. Beside the power they hold, some even post-retirement, what these revelations show is how rampant corruption has been. With so many present and former officials facing court proceedings, there is still a palpable sense that we are only scratching the surface. The iceberg still lies beneath it. Such massive presence not only indicates the normalisation of corruption, but also serves as a boost to the corrupt-minded.

Undeserved rewards and honours

Another lifeline or boost granted to the corrupt is the possibility of getting state rewards and recognition, so long as they are connected to the powers that be. The case of former IGP Benazir Ahmed, who was given state honours despite his controversial record, exemplifies this trend. But we are only getting to know about it now, post-retirement, which raises the question: how many such cases have there been? What really influences the decision to recognise state officers? Their service record, or political connection? Or is it their strategic importance to the government? Whatever it is, honesty is certainly not among the criteria. The implication of handing what serves as a symbolic victory to a potentially corrupt person—and all the way in which they can further shield themselves or advance their careers using such honours—cannot be stressed enough. Over the years, we have also seen how once-revered state awards for writers have been made objects of ridicule because of overzealous bureaucrats lobbying for their own candidature, and they sometimes got their way.

Culture of no resignation

Scandal-hit top officials, politicians, MPs, vice-chancellors or anyone like them rarely, if ever, resign in Bangladesh, even amid public protests. A common refrain among those under pressure to step down from their positions is that they will only do so if directed by the prime minister, indicating a culture where political loyalty supersedes accountability. Their connection and conviction further undermine what few accountability mechanisms we have left, however fragile. But this culture of no resignation does give the corrupt a boost, heightening their sense of inviolability so long as they have the government's support. And they usually do—unless, suddenly and quite inexplicably for the public, they don't.

Retirement benefits

This is another stage where the corrupt win big. Even if it comes to all employees regardless of how ethical they have been during their tenure, it adds to the overall appeal of civil service for the corrupt-minded. Being able to reach the finish line unpunished, and bow out with a fat pension that the majority of the population cannot even think of, is indeed a motivation. A lot can be said about the ongoing debate on the new universal pension scheme—with different, discriminatory hierarchies for government officials and others in the public sector—but that's for another day.

Post-retirement support and opportunities

The last lifeline may come in several forms, including one recently shown by the Bangladesh Police Service Association (BPSA) that extended unquestioning support to Benazir Ahmed as it lambasted the media for its coverage and even seemingly made threatening overtures. The message that other professional bodies likely got from its public statement is that they have a duty to protect their members regardless of whether they are in service or not. General members of police forces, which usually are among the groups most talked about in any discussion on human rights, should be particularly happy for the active role being played by the BPSA to represent them in public forums, but corrupt police officers will take note, too.

But what adds more to the destabilising appeal of civil service in Bangladesh has to do with the enduring influence of partisan loyalty. Loyal retiring top officials may not only see their tenure extended, but also secure cushy positions in some statutory bodies. Some may even transition into active politics, perpetuating the cycle of patronage.

In the end, I must say my analysis is based on the worst-case scenarios and corrupt trends reported in the media, and is in no way a denigration of honest officials who I would like to believe are as many in number as their dishonest counterparts, if not more. But despite the latter's unchecked activities and collusion with unscrupulous entities across all sectors, the government has waxed lyrical at best, like Obaidul Quader did, or totally ignored it at worst. It only shows how entrenched corruption is. To the government, any loss of image or public resources owing to corruption seems to be an acceptable one so long as it has a pliant bureaucracy doing its bidding.

Since independence, at least 16 commissions and committees have recommended reforms to create an efficient, merit-based civil administration, but those have been largely ignored. It is not difficult to understand the reluctance of bureaucratic and political leaders. For civil servants, especially those in high-ranking positions, reforms that promote efficiency, meritocracy and accountability represent a threat to their influence, benefits and promotional prospects. Political leaders also do not want to embrace change as it is easier to maintain control over a weak bureaucracy. But without taking on the system, and the many layers through which it sustains itself, corruption can never be tackled.

Badiuzzaman Bay is assistant editor at The Daily Star. He can be reached at [email protected].

Views expressed in this article are the author's own.

Follow The Daily Star Opinion on Facebook for the latest opinions, commentaries and analyses by experts and professionals. To contribute your article or letter to The Daily Star Opinion, see our guidelines for submission.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments