Otherness and invisible identities

Shah Tazrian Ashrafi doesn't shy away from telling it like it is. His debut short story collection, The Hippo Girl and Other Stories, holds up a mirror to a society that judges and ridicules those that do not adhere to its shortsighted vision of a homogenised culture.

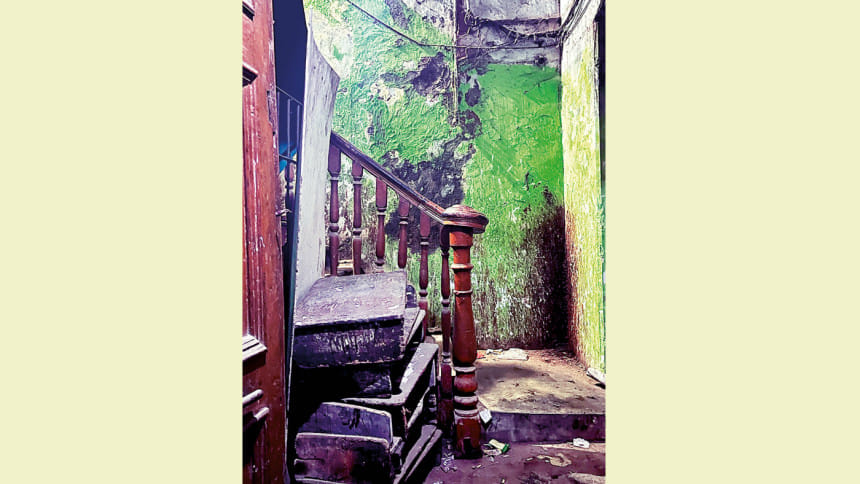

Ashrafi's characters are defiant, unruly, nonconformist. They revel in their obvious differences, bravely holding themselves firm and unrepentant in a society that values conformity. They are an accepted nuisance, yet they are complacent in that societal viewpoint. Ashrafi's stories grip you by the shoulders and transport you through the grubby, seedy, and ruthless mohollahs of Dhaka, through pre- and post-Liberation War Bangladesh, and sometimes to serene and peaceful landscapes of remote villages as well.

Set mostly in Bangladesh, the stories are distinctly Bangali. They focus on otherness, on those who are ignored, neglected, and forgotten although they cohabit the very same space as the 'respectable' class; whose identities don't matter, who are shoved aside, under grass and hard earth and life, so much so that they tend to become invisible.

If "Brother", the first story of the collection is aggressive and uncomfortable, "Lucky", the second, is strangely entertaining, humorous, tragic, and shocking. One is dark, the other is darkly humorous. In the titular story, "The Hippo Girl", the protagonist Jhonaki's acceptance of her parents' death and her subsequent obsession with hippos is beautifully captured in a brief sentence, "It was as if grief didn't want to enter her body, so it gently stepped aside and made way for the obsession to settle instead."

Death is a constant in most of the stories. Deaths resulting from desolation and destitution—shocking, disturbing, bloody. Deaths of humans and animals alike. It almost appears as if the protagonists of Ashrafi's stories are stoic, indifferent, even apathetic. But delve a little deeper and there is a hidden, desperate plea. The following lines depict the apathy only too well: "We realized Jhonaki wasn't okay when relatives and friends of the two were simmering with sorrow but not a single tear rolled out of her eyes. Instead, she emptily stared at the bodies lying in pools of dark blood on the earthen floor, walked towards the big mound of hay beneath the neem tree where the one-eared hippo was snoozing, settled herself cozily against its wet belly, and like a baby in its mother's embrace, fell asleep."

The Hippo Girl is narrated by a group of students who are classmates of the protagonist. The storytelling using the collective point of view as opposed to the singular is clever and effective. It confirms the narrowmindedness of a hypocritical society and a gradual rise in egotism.

The Hippo Girl is narrated by a group of students who are classmates of the protagonist. The storytelling using the collective point of view as opposed to the singular is clever and effective. It confirms the narrowmindedness of a hypocritical society and a gradual rise in egotism.

While there is a distinct similarity between "Lucky" and "The Hippo Girl", both with young, orphaned, homeless girls with strange inclinations and an unusual kinship with animals, the latter is provided agency and succeeds in avenging the merciless murder of her animal 'friend'. Animal cruelty, especially humans' nefarious behaviour towards street animals, is a recurring theme. In "My Human", canine loyalty is challenged in the aftermath of the Liberation War of 1971. With this and the other stories, there is an underlying theme of violence throughout the short story collection with little reprieve. This, at times, especially at this time and given the atmosphere of violence spreading across the globe, contributes to an overwhelming reading experience.

In "Crescent Boat", a granddaughter tries to befriend her estranged grandfather to discover that had transpired between her mother and him to tragically drive them apart for life. Ashrafi utilises the second person narrative for "Indira Road" and "Unpleasant conditions", two disparate stories that pay homage to the motherland. In the former, the reader imagines themselves as the narrator travelling along the alleys and laneways of their old neighbourhood in search of their mother who was abducted by West Pakistani soldiers during a military raid in 1971. By far the most tragic and heartbreaking, the reader is taken into the mind of a young man grappling with a sense of unending loss. In the latter, readers are taken to Canada where a middle-aged woman challenges perceptions of motherhood through her own experiences as a single mother.

Ashrafi is a truly gifted writer and a promising addition to the South Asian literary scene.

Nabilah Khan is a writer based in Sydney, Australia.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments