Obstetric violence and women’s human rights in Bangladesh

Safe motherhood entails a serious consideration of ensuring safe maternal and reproductive healthcare services. Yet, women in our country often face the challenge of trading off their health safety for childbirth. Last year a case was filed against a private hospital and its concerned doctor on the grounds of alleged botched Cesarean sections (C-sections) and fraud following the death of 25-year-old Mahbuba Akter Akhi. C-sections which practitioners are advised to follow in exceptional childbirth scenarios have become a common phenomenon in Bangladesh. Such procedures have become so pervasive over the years that normal delivery procedures are nowadays almost an exception—practitioners follow C-sections even when such procedures are not required. The rate of unnecessary C-sections in Bangladesh rose to 51% between 2016 and 2018 as reported by Save the Children. When we perceive these unnecessary C-sections simply as a medical procedure, we ignore the abuse, coercion, and trauma women experience during childbirth. In fact, women often lose any sense of control over their body and reproductive health when seeking healthcare support during childbirth. Although any birthing body including trans and non-binary persons could be subject to obstetric violence, this essay focuses only on (cis) women.

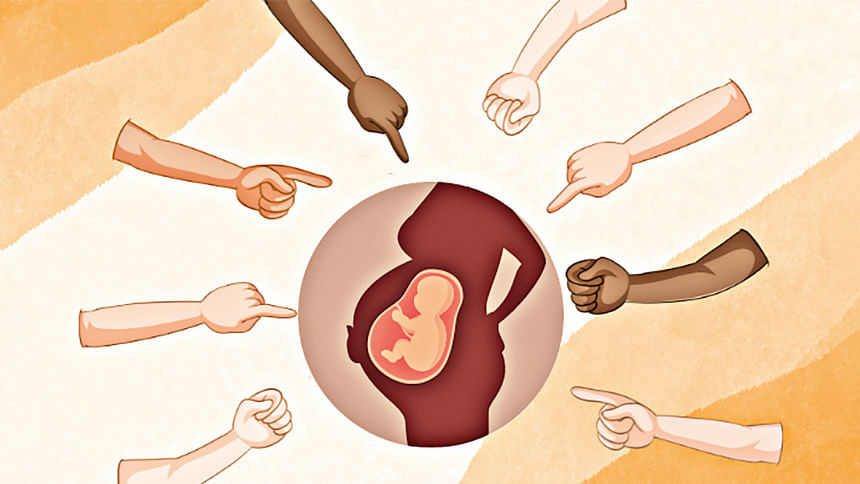

Obstetric violence is an ever-evolving concept but generally refers to the mistreatment of women including but not limited to negligence, abuse, or coercion in obstetric and gynecological care. An example of obstetric violence includes the performance of C-sections without the voluntary and informed consent of the patient. However, obstetric violence is not merely another case of medical negligence and abuse, rather an example of gender-based violence, exemplifying its dynamic nature and the various forms it takes. It is part of the broader structural violence that women face in everyday life.

The World Health Organisation (WHO) in its statement 'The prevention and elimination of disrespect and abuse during facility-based childbirth' provides an array of examples of obstetric violence such as 'outright physical abuse, profound humiliation and verbal abuse, coercive or unconsented medical procedures (including sterilisation), lack of confidentiality, failure to get fully informed consent, refusal to give pain medication, gross violations of privacy, refusal of admission to health facilities', among others. While women in Bangladesh often go through various forms of obstetric violence, it has yet to be recognised as a form of human rights concern. In fact, Bangladesh has not even recognised obstetric violence as a legal issue.

In N.A.E v Spain (2022), the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women (CEDAW) Committee, while dealing with obstetric violence experienced by a Spanish woman (the author) found that subjecting the author to unnecessary vaginal examinations, use of oxytocin without adequate justification, and performing episiotomy without consent resulted in the violation of human rights of the author under the CEDAW such as equality and non-discrimination in healthcare under Article 12, and right not to be subject to gender stereotypes under Article 5, among others. The committee further highlighted how gender stereotypes and prejudices lead to gender-based violence if medical practitioners abstain from providing women with explanations for the medical treatment they receive and deny women to express their opinions in reproductive health services.

The principle of equality and non-discrimination is a salient feature of the Constitution of Bangladesh reflecting the country's commitment to foster an inclusive and just society. Obstetric violence, however, comes in direct conflict with such constitutional values and principles because it is, I argue, a form of gender-based discrimination that occurs as a result of differential treatment of women supported by harmful gender stereotypes and cultural norms about their reproductive choices and health. Such stereotypes typically include regarding women's primary role in the society as a mother or a caregiver and, hence, the expectation that 'women should continue their pregnancies regardless of the circumstances, their needs and wishes' (Mellet v Ireland).

To undermine the opinion of a patient in obstetric care and avoid the need to help her make an informed decision also reflects the long-held discriminatory notion that women lack any agency when it comes to making any decision about their reproductive health and choices. It only reproduces stereotypes and prejudices by reinforcing the traditional gendered notion that women should be submissive and obedient and that they are without any capacity of forming opinion. While gender stereotypes and prejudices contribute to the normalisation and validation of gender-based violence during childbirth, such stereotypes about women's sexual and reproductive health eventually allow healthcare providers to take full control of women's bodies.

Obstetric violence has serious consequences for women's human rights. Therefore, instead of sweeping it under the carpet, Bangladesh needs to take obstetric violence seriously because doing so supports its commitment to international human rights treaties and its Constitutional goal of securing (gender) equality and non-discrimination.

The writer is fellow at the United Nations Development Headquarters, New York and a graduate of NYU Law.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments