A queer gaze: How Rituparno Ghosh flipped the script on female characters

In the landscape of South Asian cinema, where women have long been confined to roles of self-sacrificing mothers or objectified love interests, the films of Rituparno Ghosh emerge as a powerful counternarrative. Ghosh, one of Bengal's most acclaimed contemporary directors, crafted a body of work that challenges stereotypes and redefines the portrayal of women on screen. I try to explore their unique approach here, examining how their films subvert traditional narratives and offer a nuanced, feminist perspective on South Asian womanhood.

To fully appreciate Ghosh's contributions, we first need to understand the cinematic context they were working within. Commercial cinema in South Asia has long relied on reductive female stereotypes. As film scholar Asha Kasbekar notes, these movies often indulged in "hyperbole and tumescent rhetoric on the subject of Virtue and Honour". Women were typically portrayed as either the "ideal woman" - chaste, submissive, modest, and self-sacrificing - or as the "vamp" - the embodiment of uncontrolled sexuality and moral corruption. This binary representation, rooted in patriarchal ideologies, significantly limited the exploration of authentic female experiences on screen for decades and decades. This split, being so common in South Asian films, left little room for the portrayal of complex, multidimensional women. Ghosh's approach represents a significant departure from these traditional portrayals. Instead of the self-sacrificing ideal or the morally corrupt vamp, their female characters are nuanced, conflicted, and deeply human. These characters have desires and ambitions that sometimes conflict with societal expectations. They make mistakes, they question their roles, and they seek fulfilment beyond the traditional spheres of home and family.

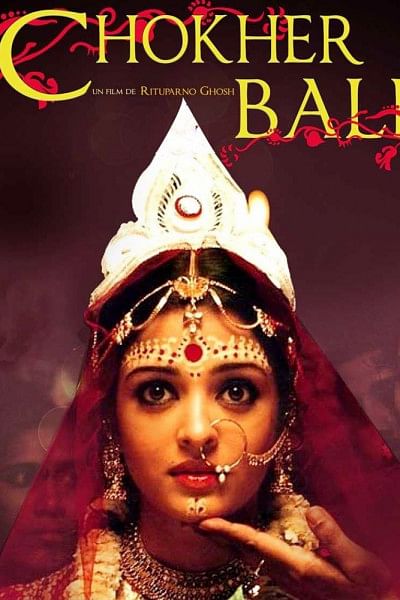

One of Ghosh's most significant contributions is their subversion of the "male gaze". Instead of objectifying women for male pleasure, Ghosh employs what we might term a "female gaze", allowing viewers to experience the narrative through the eyes of female characters. A prime example of this is in "Chokher Bali" (2003), where Binodini, a Bengali widow, uses opera glasses to observe a newlywed couple in their private moments. The camera alternates between close-ups of her eye behind the lens and her point of view through the glasses, effectively placing the audience in her position. What's striking about this scene is how it inverts the traditional dynamics of observation in cinema. Typically, it's the male characters who are given the power to observe, often in voyeuristic ways. Here, it's Binodini, a widow who by the social norms of early 20th century Bengal should be invisible, but becomes the observer with agency and subjectivity. As Binodini watches them, her expression is complex – a mixture of curiosity, longing, and perhaps a hint of mischief. This nuanced portrayal resists simplistic categorisation. Binodini is neither the chaste, self-denying widow nor the scheming temptress. Instead, she's a complex woman with her own desires and agency.

It's worth noting that Ghosh's use of the female gaze goes beyond simply reversing the power dynamics of traditional cinema. Binodini's gaze is not objectifying in the way the male gaze often is. Instead, it's curious, empathetic, and complicated. When she observes the couple, it's not just with desire, but with a mix of emotions – longing, yes, but also curiosity about a life she's been denied, and perhaps a touch of resentment at her own unforeseen circumstances. This nuanced approach challenges viewers to see beyond simple binaries of observer and observed, powerful and powerless. It presents a more complex view of human relationships and social dynamics, one that acknowledges the multifaceted nature of power, desire, and identity.

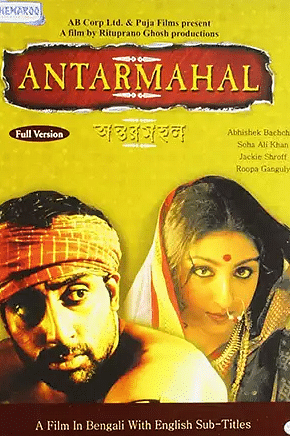

Ghosh's exploration of female sexuality is also particularly revolutionary in the South Asian context, where such topics are often taboo. In "Antarmahal" (2005), we see Mahamaya, the elder wife in a 19th-century Zamindar household. Played with nuanced complexity by Roopa Ganguly, Mahamaya is neither the submissive wife nor the one-dimensional vamp. The scene in question unfolds in the inner chambers of the haveli (mansion), a space traditionally associated with female seclusion and male control. The Zamindar, desperate for an heir, brings in a priest to chant mantras (sacred utterances) while he attempts to impregnate his younger wife. This ritual, steeped in religious and patriarchal authority, represents the intersection of spiritual and sexual control over women's bodies. Ghosh sets the stage meticulously — the room is dimly lit, creating an atmosphere of secrecy and forbidden acts. The priest sits cross-legged, eyes on the couple, chanting a monotonous drone that fills the space.

What unfolds next is a masterclass in cinematic subversion. Mahamaya sits opposite the priest and begins a silent, deliberate performance of reveal and conceal. She starts by slowly lifting the edge of her sari, exposing her ankle – a scandalous act in the conservative 19th century. The camera lingers on this small expanse of skin, emphasising its transgressive nature. The camera work here is crucial. It alternates between close-ups of Mahamaya's face, capturing her mix of defiance and calculated seduction, and the priest's increasingly flustered reactions. This intercutting serves to shift the power dynamic; Mahamaya, who should be invisible in this scenario, becomes the active agent, while the priest, a symbol of male spiritual authority, is reduced to a flustered, distracted state.

As the scene progresses, her actions become bolder. The priest's chanting falters, wavers, and stops abruptly — his eyes wide with shock and forbidden desire. Mahamaya, having achieved her goal of disrupting the ritual, calmly readjusts her sari and leaves, a small, triumphant smile playing on her lips. The broader implications of this scene extend beyond the narrative of the film. In the context of South Asian cinema, where female sexuality is often either demonised or objectified for male pleasure, Mahamaya's sexuality is neither shameful nor performative for male benefit; it's rather a core part of her identity and a source of personal power. It can also be read as a broader critique of how religious institutions often collude with patriarchal structures to subjugate women. Moreover, while in the world of commercial cinema, Mahamaya, the older, almost mid-aged wife would typically be desexualized, Ghosh portrays her as a sexual being capable of desire and seduction, contesting ageist notions of female sexuality. His treatment of this scene is also noteworthy for everything that it doesn't show. Unlike many mainstream films that might exploit such a scene for titillation, the camera focuses on Mahamaya's face and the power dynamics at play. This approach underscores that the scene is about power, not pornography.

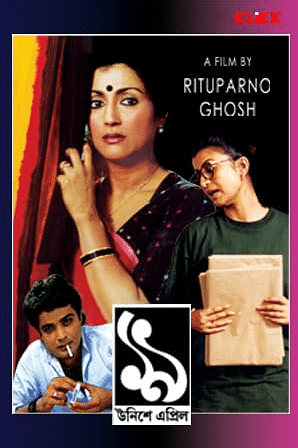

Ghosh's deconstruction of motherhood, a theme often idealised in South Asian cinema, is also particularly noteworthy. One of their earliest films, "Unishe April" (1994) centres on the strained relationship between Sarojini (Aparna Sen), a renowned classical dancer, and her daughter Aditi (Debashree Roy), a doctor. From the opening scenes, Ghosh subverts traditional expectations of motherhood. Sarojini is not the warm, self-sacrificing mother typically seen in Bengali cinema. Instead, she's portrayed as distant, career-focused, and often dismissive of her daughter's feelings. In one pivotal scene, when Aditi reminds Sarojini of the significance of the date – her father's death anniversary, Sarojini's response is curt and unsentimental. She has forgotten the anniversary, prioritising a celebration for an award she has received for her dancing. This moment encapsulates the film's central conflict: the tension between Sarojini's identity as a mother and her identity as an artist. Ghosh refuses to present this as an easy choice or to judge Sarojini for her priorities. Instead, the director invites the audience to consider the complexity of her position.

In a powerful monologue, Sarojini finally reveals the sacrifices she made to pursue her art, including facing societal judgment and her husband's resentment. "I too had dreams," she tells Aditi, challenging the assumption that motherhood should automatically supersede all other aspirations. This scene is particularly significant in the South Asian context, where women are often expected to sublimate their personal ambitions to their roles as wives and mothers. The film also explores the impact of this complex mother-daughter relationship on Aditi. We see her struggling with her own identity, torn between admiration for her mother's accomplishments and resentment of her emotional absence. But Ghosh resists the temptation to present her simply as a victim of maternal neglect. Instead, Aditi is shown as a grown woman grappling with her past, trying to understand her mother even as she struggles against her influence.

The climax of the film comes in a raw, emotionally charged confrontation between mother and daughter. Years of misunderstandings and unspoken grievances come boiling to the surface. Ghosh's screenplay shines here, with dialogue that feels painfully real. Neither character is entirely right or wrong; both are flawed, humane, and struggling to connect across a gulf of hurt and misunderstanding. What's particularly revolutionary about this performance is its honesty. Ghosh doesn't shy away from the ugly aspects of family relationships - the resentment, the miscommunication, and the way the past hurts can poison the present. By presenting these difficult emotions without judgment, they validate the complex, often painful reality of many mother-daughter relationships.

Now that I think back on these denoting factors, I feel Rituparno Ghosh's identity as a queer person likely played a significant role in their nuanced and empathetic deconstruction of female characters. As someone who existed outside traditional gender norms, did the filmmaker have a unique perspective on the societal pressures and expectations placed on women? Did this outsider's perspective, combined with their innate sensitivity as an artiste, enable Ghosh to see beyond the stereotypical portrayals of women common in South Asian cinema? Their exploration of Binodini's liminal status as a widow, Mahamaya's subversive sexuality, and Sarojini's conflict between motherhood and personal ambition all reflect a deep empathy for individuals navigating complex social structures. Their films consistently show women carving out spaces for themselves, asserting their desires, and challenging societal expectations - themes that resonate strongly with the queer experience. In this way, Ghosh's queer identity becomes not just a biographical detail, but a crucial lens through which the director viewed and reconstructed notions of gender, sexuality, and identity in his cinema.

As we celebrate what would have been Ghosh's 61st birthday today, their legacy in South Asian cinema stands as a testament to the power of representation and the importance of diverse voices in storytelling. Their work continues to inspire filmmakers and audiences alike, encouraging a more nuanced, empathetic, and inclusive approach to portraying women on screen. In a world still grappling with issues of gender equality and representation, Rituparno Ghosh's films remain not just relevant, but essential viewing, offering a vision of cinema that truly sees and values women in all their complexities.

The author is a lecturer at University of Liberal Arts Bangladesh (ULAB).

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments