China’s global battery ram will be hard to stop

China's electric cars have zoomed into a new era of battery-powered driving. Now models such as BYD's Seal and Great Wall Motor's Funky Cat face an international backlash. The US is quadrupling duties on imports of electric vehicles from the People's Republic to more than 100 percent, while the European Union is lifting total tariffs close to 50 percent for some marques. The Chinese-made batteries that power the vehicles are an obvious next target for trade restrictions. But that battle will be even harder for the West to win.

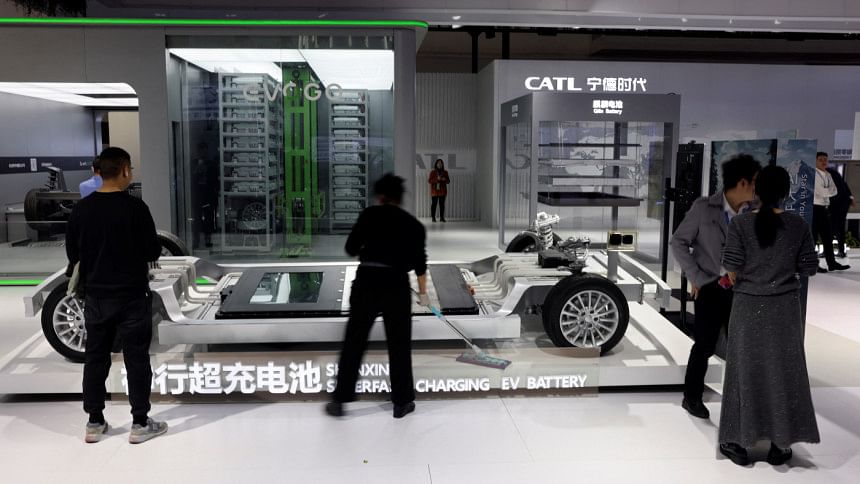

China is a battery powerhouse. The $115 billion Contemporary Amperex Technology , and its smaller compatriots accounted for two-thirds of the global market for power cells used in electric cars in the first half of 2024, Bernstein analysts reckon. Companies from the People's Republic are also growing faster: installations by SVOLT Energy Technology more than doubled in the period from January to June, while those from rivals CALB, Guoxuan, CATL and BYD all grew by more than a fifth compared to 2023. They're profitable too, with CATL raking in more than 40 billion yuan ($5.6 billion) in earnings last year.

Much of that output is exported: the total volume of lithium battery units leaving China roughly doubled between 2015 and 2023, according to the International Trade Centre. The US and Europe have become major buyers of Chinese cells, squeezing local operators like Sweden's Northvolt.

Now Western policymakers are pushing back. President Joe Biden in May laid out plans to hike tariffs on imports of batteries and their parts to 25 percent, from the previous 7.5 percent. His flagship Inflation Reduction Act, which subsidises electric cars by up to $7,500, from 2025 explicitly excludes vehicles for which battery materials were extracted, processed or recycled by a "Foreign Entity Of Concern, ". That term covers companies headquartered or incorporated in China, and firms where the government holds 25 percent or more of its equity, voting rights or board seats. Chinese manufacturers are also excluded from the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law's $6 billion of credits for batteries and the critical minerals required to make them.

EU policymakers in Brussels are erecting similar barriers for Chinese-made batteries. They have not introduced additional tariffs, but a slew of guidelines on local and responsible sourcing makes trade increasingly costly and complex. So will the EU's proposed carbon border tax, which will impose levies on emissions-intensive imports, including cars and related parts from 2030.

These efforts are likely to intensify as political relationships become testier. US efforts to minimise the country's dependence on its main strategic rival have broad bipartisan support. Officials are also anxious about the presence of Chinese tech in so-called dual-use products that have military applications. Batteries are crucial for submarines and drones.

And although the IRA is one of Biden's signature policies, Donald Trump would probably hesitate to reverse it wholesale if he returns to the White House. Battery-related investments spurred by the tax credit scheme are concentrated in Republican-leaning states, UBS analyst Tim Bush points out.

To successfully unplug from Chinese suppliers, however, Western countries will need to develop alternatives. Korean battery giants such as LG Energy Solution, SK On and Samsung SDI, which account for a combined global market share of 23.5 percent, are expanding in the US and the European Union. However, relying on this trio has downsides, because they lag larger Chinese rivals' technical prowess. None have so far managed to ramp up mass production of increasingly popular lithium-iron phosphate cells, for instance.

Developments in battery technology may allow upstarts to leapfrog established leaders. The most promising prospect is solid-state batteries, which use a lithium-metal layer in place of a conventional anode - the part of the device to which current travels during charging. This offers higher energy density so that the pack powering a car can be safer, smaller, and lighter without sacrificing range.

Pioneers are jostling to bring the science out of the lab, and no one has a clear lead. Benchmark Minerals predicts that by 2030 the US and China could each account for around a third of the market for this chemistry. Chinese leaders including CATL and BYD are exploring solid-state batteries. The world's largest carmaker, Toyota Motor, says, it could be as little as three years away from putting vehicles using those products on the road. Volkswagen , is partnering, with New York-listed QuantumScape, to do the same.

Yet overtaking Chinese battery makers is a tricky proposition. Solid-state products still use lithium, and some versions also require graphite, nickel and cobalt. Although China holds only around 7 percent of the world's lithium reserves, it controls around 80 percent of lithium chemical production, according to the Organisation for Research on China and Asia, as well dominating in nickel and cobalt. The People's Republic has such a tight grip on graphite that the United States recently had to push back restrictions on overseas supplies. Battery makers including Ford Motor, are urging the US Trade Representative's Office to ease proposed duties on imports of the material, Reuters reported last week.

If engineers concoct new recipes for cathodes and anodes, processing the necessary materials would probably still be less costly in China. The country currently churns out batteries at about three-quarters of the price of those made elsewhere. Research and development are more affordable in the People's Republic, too. Researchers accounted for 80 percent of BYD's record recruitment, last year.

A large domestic customer base offers Chinese companies a vast testing ground that allows them to scale and commercialise new ideas quickly and cheaply. Nearly two-fifths of global patent applications relating to solid-state batteries come from China, according to local media.

State support further defrays costs. Last year, CATL was the top corporate recipient of government grants, the Nikkei reported. The company pocketed more than $800 million, in 2023, double the 2022 figure, according to the Center for Strategic & International Studies.

Chinese stakeholders are not taking the status quo for granted. In January, a Tsinghua University professor warned China could lose its lead in batteries if it was not prepared for the risks posed by the rise of new technology. The state is coordinating a project involving six companies and investments of more than 6 billion yuan to incubate solid-state technology, Reuters reported in May, citing sources.

It's too soon to declare victory in the war for the next generation of battery technology. However, it is currently hard to imagine China losing its edge in both mass production and innovation. Opting out of those products will make electric cars more expensive and less sophisticated. Beijing's global battery ram looks very hard to stop.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments