Evolution of Jamdani and the role of BSCIC -- challenges and prospects

There are differing opinions regarding the evolution of Jamdani, but the most widely accepted view is that both Jamdani and Muslin originated simultaneously.

Muslin is known for its single-color monotone feature while Jamdani has intricate designs, often involving mixed, crisscrossed colours and textures.

The origin, development and expansion of Jamdani took place primarily in the greater Dhaka area, particularly in Rupganj and Sonargaon of Narayanganj, adjacent to the Shitalakshya River.

If we look back at the remarkable journey of Jamdani, we find that the Mughal period was its most prosperous era. The region around Shitalakshya was blessed with natural 'kapas'—soft cotton fibres—and the waters of the Shitalakshya, Brahmaputra, and Meghna rivers, which contain rich minerals and ideal moisture and heat to boost Jamdani production.

Thanks to rapid industrialisation and urbanization, conditions have changed along the banks of these rivers, which have severely affected the once-pristine waters.

Jamdani is a cottage industry product, meaning it is produced by families working together. To truly understand the craft, one must observe it first-hand to appreciate the immense passion and effort required to complete a Jamdani piece.

It is akin to wizardry and one has to start working in the field at a younger age to become skilled in this profession.

After years of meticulous attention to detail, an amateur weaver transforms into a skilled craftsman – a true wizard of Jamdani.

To preserve and develop this rare heritage, the Bangladesh Small and Cottage Industries Corporation (BSCIC) first took the initiative in the 1980s, later acquiring 20 acres of land in 1993 to establish a special industrial estate exclusively for Jamdani production on the banks of the Shitalakshya River at Noapara of Rupganj in Narayanganj.

By 1999, BSCIC had completed the establishment of the Jamdani Industrial Estate.

Before allotting plots to the Jamdani entrepreneurs and skilled craftsmen, the BSCIC conducted a survey to ensure that only dedicated and passionate individuals receive the plots.

Since 2001, the Jamdani Industrial Estate has been fully operational, currently housing 407 industrial plots for Jamdani weaving.

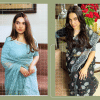

Jamdani craftsmen typically produce three types of products: saris, two-piece and three-piece outfits for women, and panjabis for men.

The primary product is the sari, available in a variety of colours and textures, including single, double, mixed, or crisscrossed patterns and in full silk, half-silk and full cotton varieties.

To promote this rare heritage, the BSCIC, as the parent organisation of the Jamdani Industrial Estate, organises three types of Jamdani fairs across the country.

One is held during the Pahela Baishakh at the Bangla Academy premises, and the others in Dhaka and Chattogram during Ramadan.

Additionally, Jamdani entrepreneurs frequently participate in fairs organised by the BSCIC district offices nationwide as well as in events hosted by the deputy high commission of Bangladesh in Kolkata and various states in India.

Some are also involved in online business.

A proud moment for Jamdani weavers came when their craft received recognition from the UNESCO as an Intangible Cultural Heritage in 2013 and in 2016 when Jamdani became the first-ever geographical indication (GI) product from Bangladesh thanks to the efforts and collaboration of BSCIC and the industries ministry.

The declining number of new Jamdani weavers is a significant concern. There was a time when family members naturally joined the trade, but those days are fading.

Low wage is a major reason for the weavers to leave the labour-intensive industry.

The financial rewards simply do not match the effort required.

The intricate designs and textures of Jamdani are at risk due to these challenges.

The highly industrialised nature of the region has led many potential craftsmen to switch professions in search of a better pay in other industries.

Additionally, producing a high-quality Jamdani product requires years of focused effort, often starting at a young age, which conflicts with Bangladesh's labour laws.

Moreover, exploitation by large clothing brands means that the financial benefits rarely reach the weavers.

The issue of counterfeit Jamdani, particularly from India, is another significant problem. These machine-made, cheaper imitations have severely impacted the Jamdani market. This must be addressed to protect the integrity of the Jamdani brand.

Recognition is also an issue. While the product itself has gained recognition, the weavers as professionals are yet to receive the perks and financial benefits they deserve from the recognition.

In true sense, the benefits from the UNESCO recognition and GI status have primarily gone to the large clothing brands rather than the weavers themselves.

Capitalist exploitation by large clothing brands is again to blame for the weavers being deprived of the financial benefits.

There are numerous instances of large brands selling Jamdani products at prices which are double or way higher than the payments weavers received.

The government should take initiatives to protect this from capitalist exploitation.

On a positive note, the global attention and support from the Bangladeshi diaspora offer hope. Those living abroad, who are often more financially stable than those in Bangladesh, tend to purchase this rare heritage, sometimes even at better prices, which motivates weavers and helps preserve this national treasure.

Organising more fairs nationally and globally is crucial to making Jamdani financially viable. Cities like Dubai, London, New York, Kolkata, Delhi, and other areas with a significant Bangladeshi diaspora can be strong markets for this product.

Especially in India, a major cultural hub, people have a deep admiration for this product.

Many are willing to pay more when they learn it is authentic Dhakaiya Jamdani. Several Jamdani weavers have shared this experience from their visits to India for fairs.

As a GI product and UNESCO Intangible Cultural Heritage, Jamdani has global appeal.

Organising fairs ensures that the financial benefits eventually reach the grassroots level of this industry.

Despite these challenges, there is a silver lining. BSCIC, under the supervision of the Ministry of Industries, is conducting a training programme at the Jamdani Industrial Estate to train aspiring weavers, particularly women who have unoccupied time.

This initiative not only helps these women contribute to their households but also aids in preserving this rare heritage.

Additionally, some Jamdani entrepreneurs and skilled craftsmen continue to hold this tradition as their inheritance, their emotion, and their pride, both in Bangladesh and across the world.

To protect and develop this sector, BSCIC and the Ministry of Industries have already taken several steps to ensure the preservation of both the product and the weavers.

In this era of intense capitalism and widespread online engagement, it is crucial that Jamdani weavers receive government support across all necessary channels and sectors.

Any benefits derived from this product should primarily go to the weavers.

I sincerely hope that with the support and efforts of all senior departments and authorities, this rare heritage and source of pride will continue to thrive for many years to come as our own.

The writer is a former industrial estate officer of the BSCIC Jamdani Industrial Estate.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments