Police reform: Freedom from political control is the goal

The setting up of a commission for police reforms is not the first such move in Bangladesh.

The last caretaker government had taken a similar step. It formed Bangladesh Police Act Drafting Committee, which came up with a draft ordinance in 2007.

The goals of the committee were to free police from political influence; make transfers, promotions, and appointments within the force transparent; and ensure that the force and its members are accountable.

That draft ordinance proposed an independent police commission and a complaints commission. It intended to change the colonial police laws of 1861, but it never saw the light of day because of strong opposition from the bureaucracy and vested quarters, said those involved in the process at that time.

Drawn up with assistance from Police Reforms Programme (PRP), funded by the UK and EU, the ordinance was forwarded to the home ministry in 2008 for promulgation, but it never happened.

One of two police officials, who were involved in drafting the ordinance and are still with the force, said the home ministry controls promotions, postings, and punishment of all officers above assistant superintendents according to the wishes of the party in power.

"But under the new law [proposed ordinance], the bureaucrats would not have any control over the police."

Citing the examples of India and Sri Lanka, they said both the South Asian neighbours have changed their British era police laws, since those were designed mainly to subjugate people and required hardly any accountability for police.

The officials suggested that the new police reforms commission, led by former home secretary Safar Raj Hossain, may draw upon the draft ordinance and the experience of Sri Lanka.

The two officials, speaking on condition of anonymity, said the Sri Lankan law was better than that of India or Pakistan.

They cited the example of the uprising in Sri Lanka and the ouster of president Gotabaya Rajapaksa, during which the police did not use lethal force on protesters. They did not face public wrath either. "That is because Sri Lanka's police is controlled by an independent commission," said one of the officers.

The 2007 draft had proposed a National Police Commission (NPC) and a Police Complaint Commission (PCC) to supervise policing and reduce partisan influence in the police department. The police commission would be headed by the home minister, it would have MPs from both sides of the aisle along with civil society representatives.

The complaints commission would be headed by a former judge of the appellate court along with senior retired bureaucrats and civil society representatives.

But once the Awami League took over in 2009, there was no attempt to reform the police. In fact, the AL government used the entire force as its tool for repression and to subdue opposition and dissent.

A section of police officials also worked as party activists for personal gains like securing lucrative postings and engaging in rampant corruption. In the process, they not only deprived the more competent officials, but were able to push them out to the fringes with their own groups of loyalists that had turned into an evil axis.

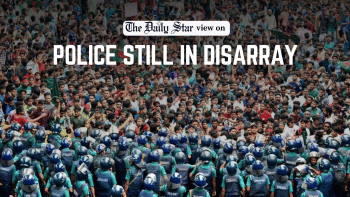

The axis showed its true colours during the July-August protests, when hundreds of people were shot dead by police. According to the latest estimates, at least 708 people were killed.

The law enforcers also suffered at the hands of the people who turned on them as the protests culminated in an uprising. The protesters killed 44 policemen, burnt down 224 police establishments and vandalised 236. Several police stations were razed to the ground.

Police reforms commission chief Safar Raj told The Daily Star on Sunday that his committee members had already been picked and would soon be given formal appointments.

He added the commission will seek opinions from all stakeholders, including representatives of the print and electronic media.

Yesterday, the names of the commission members were unveiled by a notification.

The commission's office is at the home ministry.

However, those involved in the draft ordinance cautioned that even being located within the home ministry made the new commission vulnerable to pressure from bureaucrats.

THE 2007 DRAFT ORDINANCE

The draft ordinance proposed a National Police Commission (NPC) to supervise and administer the force and a Police Complaint Commission (PCC) to hold it accountable. The overarching goal was essentially the same as that of the Safar Raj Commission, reduce partisan influence.

The 11-member NPC would be led by the home minister. Members would include four MPs (two each from the government and opposition), four civil society representatives, the home secretary and the police chief. This police commission was authorised to significantly contribute to the appointment of the police chief and investigate any allegations against the top cop. Furthermore, only this commission had the authority to fire or transfer the inspector general.

The NPC would also finalise three nominees for the post of inspector general and forward them to the government for a final selection. The ordinance proposed that the government would appoint senior police officials, like additional IGP, upon the advice of the police commission.

Besides, the police commission would have to periodically make recommendations ensure an efficient, effective, and accountable force.

Striving for stability within the force, the draft proposed that between the ranks of superintendent and inspector general, officials would remain at a post for at least two years.

The proposed ordinance criminalised any recommendations for appointments, transfers or promotions whether by a minister or an MP.

The five-member complaint commission was authorised to investigate any complaint against the police, abuse of power, violation of human rights, negligence and corruption.

The PCC, led by an Appellate Division judge or nationally reputed personality, would include a retired secretary or additional secretary, a retired IGP or additional IGP and two neutral civil society representatives.

The complaint commission would have had the authority to act voluntarily or on the basis of complaints. It was authorised to refer complaints of minor offences back to the police authorities and had the powers to investigate complaints it deemed serious. It could ask the chief justice to appoint a district judge for a judicial inquiry if it needed to.

The PCC was also given the responsibility to draw up recommendations for ridding the police force of corruption. This commission would closely supervise investigations related to all killing and rape. The draft ordinance had a provision for forming a summary court to swiftly punish police officials found guilty.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments