Of Hilsa and its hunters

On the corner of a crowded and noisy floor, a bespectacled man was calling out bids for a basket of Hilsa fish. He repeated the prices quoted by traders in a loud, rhythmic tone: "1,400-1,420-1,450…"

In front of him, traders, packed like sardines, struggled to find balance as rickshaw vans, loaded with large white boxes of frozen fish, barrelled their way through the crowd, unbothered by the prospect of someone's feet being crushed beneath their wheels.

The auctioneer, likely in his fifties, finished his calls in a minute and asked his mates to weigh the Hilsa. The scale showed over 27 kilogrammes (kgs) in the batch, prompting the bespectacled man to open and mark the red tally book in his hands.

The buyer cleared the price at Tk 1,420 per kg, the maximum bid. A porter emerged, took the basket of the Hilsa, and vanished into the crowd.

Nearly the same scene unfolded again, as the auctioneer began to call for bids for the next lot, displayed on a large flat pan. The only difference was that this lot had a larger amount of fish, but each was smaller in size.

He opened the auction with a floor price of Tk 800 per kg.

This was the scenario at one of the largest fish hubs in Dhaka, Karwan Bazar, which is teeming with life before the sun rises and the denizens of one of the world's most densely packed metropolises awake.

Small traders from different parts of the capital throng Karwan Bazar to purchase Hilsa and other fishes at wholesale prices before selling them to consumers at kitchen markets across the city.

Commission agents, popularly known as aratdars or mohajons, dot the market, receiving fish sent by suppliers from across the country.

In the case of Hilsa, supplies come mostly from the coastal districts: from Barguna and Patuakhali in the south to Bhola, Chattogram and Cox's Bazar in the southeast.

Fishermen harvest the fish from the Bay of Bengal, rivers, estuaries and from the coastlines before bringing them to aratdars.

Thus, the Hilsa trade begins.

"Our catches are auctioned after we bring them to aratdars," said Islam Hawlader, a small fisherman in Patuakhali, one of the 10 lakh who depend on Hilsa for their livelihood.

The trade of the most popular fish in the country, accounting for more than 12 percent of total annual fish production in Bangladesh, largely operates under a credit-based system widely known as "dadon".

Under the arrangement, aratdars provide fishers with informal loans for repairs and equipment as well as working capital to purchase fuel, ice, food and other necessities.

These loans are given with the condition that fishers deliver their entire catch to lenders for profit-sharing.

Often, aratdars in major cities provide dadon or credit to their suppliers, who themselves are aratdars in fish landing stations at the local level.

The suppliers then provide credit to fishing boat owners.

Both sets of aratdars collect commissions on the proceeds from the sales of any eventual catch, be that at landing stations or in Dhaka.

However, in some cases, established aratdars near landing stations can finance operations themselves, with no need to pay any commission to someone back in the capital.

Two to six percent commission was collected on all fish auctioned by aratdars, according to a paper published by the Bangladesh Fisheries Research Institute (BFRI) in June 2020, titled 'Hilsa Fisheries Research and Development in Bangladesh'.

After deducting the commission as well as initial loans from the sale price, aratdars charge Tk 10 per kg of Hilsa as charges.

The remaining amount is divided among boat owners and fishers.

However, this is not done equally. Instead, boat owners get half of the remaining amount while the remaining half is divided up among fishers and the head boatman.

Of that half, the head boatman gets two shares while each fisherman gets one share, according to Hawlader.

However, if they do not get fish in abundance, there is the risk that they will all remain indebted to the aratdar.

"It is a vicious cycle. We don't have enough money to invest in Hilsa fishing so we have to get money from radars," said Delwar Gazi, president of Mohipur Fishing Trawlers Owners Association, a major fish landing station in Patuakhali.

In its publication, the BFRI said Hilsa fishers are among the poorest and most vulnerable section of the population.

Most of them are landless and their annual income amounts to only Tk 60,000 to Tk 80,000.

"So, they live a very substandard life with no savings. They cannot afford to buy or hire fishing equipment and bear the cost of operating fishing boats in rivers and seas," the publication mentioned.

Fishers and traders said Hilsa changes hands at four to six levels. Fishermen first hand over catches to aratdars at landing stations, who then dispatch them to wholesalers. Wholesalers sell it on to retailers, who finally deliver the goods to the consumers.

This unsavoury flavour translates to the methods of sales for Hilsa, primarily auctioning and price-fixing.

Traders said wholesalers quote prices considering the existing rates and availability in the market.

Islam and Delwar said their catches are auctioned at Mohipur, where local and inter-district wholesalers as well as representatives of aratdars take part.

They spoke about another part of the seedy underbelly of the Hilsa trade.

"Sometimes aratdars buy the Hilsa to stockpile. This takes place especially when there is increased supply and low presence of wholesalers," he said.

The other method, price-fixing, has a more sinister tinge.

For example, in Cox's Bazar, Hilsa is sold at predetermined or fixed rates by aratdars and wholesalers.

"Wholesalers fix prices here based on information of the market rate in other major landing stations," said Delwar Hossain, general secretary of the Cox's Bazar Fishing Boat Owners Association.

"We, the boat owners and fishermen, are deprived of fair prices because wholesalers fix low rates in collusion with dadon providers," he alleged.

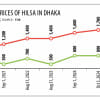

"A Hilsa fish weighing 1kg is bought from us at Tk 900 each and sells in Dhaka for Tk 1,400."

In Patuakhali, Gazi voices similar grievances. "In Dhaka, a Hilsa over 1 kg is sold at Tk 2,000 whereas we get around Tk 1,500 for the same."

Those allegations are far from unfounded. During a drive in Jatrabari last month, the Directorate of National Consumers' Right Protection found that Hilsa was being sold at prices 51 percent higher than wholesale prices: hiked from Tk 1,450 per kg to Tk 2,200 per kg.

The directorate added that fish were being sold without receipts or vouchers.

Gazi said fishers could get better margins if they could sell catches themselves away from the shadow cast by aratdars.

"But because of the dadon system, we can't. We have to sell our catch to them. We could have been free of the shackles of aratdars if we had access to formal credit," he said.

"But neither banks nor NGOs provide us with loans."

However, even if boat owners get access to formal credit, the hardships plaguing Islam and fishermen like him are unlikely to dissipate unless the sharing system is changed.

The BFRI publication said Hilsa fishing is profitable, but the distribution of profits appears to be biassed, inequitable and exploitative.

"The sharing system has created low income for actual fishermen," it said. Md Abdul Wahab, a professor of fisheries management at the Bangladesh Agricultural University (BAU), said the real harvesters of Hilsa benefit little from the high prices that consumers pay.

"Boat owners and dadon providers are the real beneficiaries," he said.

"The condition of real Hilsa fishermen has not improved, although they sacrifice a total of 143 days each year in compliance with government restrictions on Hilsa fishing."

Mohammad Saidur Rahman, a professor of agricultural economics at BAU, added: "It is not that fishermen can ensure education for their children. They have fallen into a vicious cycle. Their livelihoods will only improve if the government increases social protection for them."

The 22-day ban on Hilsa fishing starts from tomorrow.

With prohibition looming, Hawlader was looking for a good haul. He hoped he could survive the next three weeks after paying off the dadon provider.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments