The Daily Star (TDS): You have extensively researched the architecture of the Sultanate period. Could you share your thoughts on Bengal's pre-Sultanate architecture?

Perween Hasan (PH): The existing ruins from Paharpur and Mainamati speak of a rich architectural heritage from pre-Sultanate times. These viharas for resident Buddhist monks corresponding to present day student dormitories were built around a central monumental temple. Recent excavations have also uncovered new evidence of smaller temples which served the Hindu, Buddhist and Jain population of the area. The National Museum of Bangladesh in Dhaka has stone sculptures and architectural members of stone and wood that give us an idea of what some of these temples looked like. There are also illustrated Buddhist manuscripts in museums around the world that have depictions of temples in various sites in Bengal. Externally there was little difference to mark the denominations of Hindu/Buddhist/or Jain temples, the icon inside being the identifying factor.

Usually temples comprised of a small square chamber which housed the deity and had a roof that was either tiered, or had one or multiple tall towers, or a combination of both. The sanctuary was not very large because the space was meant to accommodate just the deity and the officiating priest. Sometimes there would be a porch in front from where the devotees followed the rites performed by the priest inside. There were also various folk religions which must have had their own places of worship, but whose architectural forms remain unclear. Extant and excavated temples indicate that the primary building material was brick although the manuscript illustrations as well as the architectural members in the National Museum suggest that wood was also used. Stone columns , lintels, as well as blocks to sculpt icons were obtained from Bihar, as there was no stone available in Bengal. Apart from brick or wooden examples, there must have been others--small, informally built temples made of mud, bamboo and thatch that resembled the residential huts of much of the rural population.

The primary difference between temple and mosque is dictated by its function. Whereas in a temple the central chamber housing the deity is designed to accommodate only the officiating priest, a mosque must accommodate people for the five daily prayers--collective performance of which is not mandatory but preferred. A congregation is mandatory for the Friday afternoon prayer which requires the collective participation of all male Muslims. To accommodate the Friday prayer a larger space is required and that is provided by the Jami mosque.

In conversation with Professor Perween Hasan, a distinguished historian and expert on the architecture of the Indian subcontinent.

Although there is evidence of Muslim presence in Bengal before the Turkish conquest of 1204, the earliest architectural record dates back to 1221 to an inscription of a khanqah (hostel for pious mem) in Birbhum district of West Bengal. The earliest extant monument is the Mosque at Tribeni in Hughly, West Bengal, India built in 1298. This is a typical large mosque enclosing a rectangular space with a row of arched niches (mihrabs) in the west which indicate the qibla or direction of Mecca. As historically and strategically this is a very important building its plinth, piers and parts of the external surface are faced with stone.

Most village mosques were single chambers made of mud, bamboo and thatch as in temples, perhaps larger in size, but much like the rural homes of the villagers; the only distinctive feature of the mosque being the projection of the mihrab on the west (qibla) side. Such mosques exist even today, although their numbers are diminishing, as there is a preference to build with more permanent material.

Most of the extant brick mosques built during the Independent Sultanate, early 14th till the middle of the 16th century, were small square structures made of brick commissioned by prominent or wealthy individuals. Among their distinguishing features was a dome, arched entrances in front, and a curved cornice which resembled the curved cornices of the bamboo framed eaves of the rural huts. Arches and domes were largely absent from the architectural vocabulary of Bengal before the Turkish conquest. As traveling was not easy and usually involved the navigation of numerous waterways, small mosques sufficed for people living in small village communities. Extra efforts were made to attend the larger Jami mosques on Fridays and religious festivals. Contemporary temples, of which there are no extant examples here but several in Myanmar, were likely also constructed following the basic residential hut form.

TDS: What is the significance of the arches?

PH: Although the arch form was common, arches built in the keystone and voussoir technique, also known as the 'true' arch was a rare architectural technique in India before the arrival of the Turks. In Bengal, the indigenous construction depended on a trabeate system which used posts and lintels or beams to span openings such as doors and windows in walls. The arcuate method popularized by the Turks is technically more advanced and allows the spanning of larger wall openings as well as the construction of vaults and dome. This new technique may account for the survival of some of the mosques from the Sultanate period, although their vaults and domes were the first to fall.

TDS: You mentioned in your book that the presence of a large number of rivers in Bengal had not been a barrier to communication but rather facilitated connectivity. How did geographical features like heavy rainfall and the distinctive climate impact its architecture?

PH: In this riverine terrain the villages are like small islands, specially during monsoons, and travelling by country boat was the only way to travel long distances. A natural mode of communication was in place, but as a mode of transport it was slow, specially when long distances had to be negotiated. So it was more practical to have small mosques to service small rural communities. Perhaps on Fridays and on religious festivals people would make the extra effort to travel to the nearest Jami mosque.

The distinct architectural style of Bengal was shaped by its unique geographical features. Clay found most abundantly in the delta was formed and fired to make brick, the primary building material. The curved cornice of Sultanate brick buildings was a distinctive feature that was derived from the curvature of the bamboo frames that roofed the indigenous huts made of more temporal material such as bamboo, thatch and mud. Although many mosques were built, the hot, humid climate largely contributed to their deterioration. The thick brick walls had a veneer of dressed brick with lime mortar, while the inside was filled with brickbat masonry and mud mortar. These could not withstand the heavy rainfall and humidity of the region specially during the monsoon season. In some sites underground salinity has resulted in mossy floors and structural deterioration as can be seen in the Shait Gombuj Mosque in Bagerhat. Human actions also contributed to the ruin. For instance, it is believed that the city of Malda in West Bengal, India built during British rule used bricks from the ruins of Gaur, unearthed through excavations. Thus, the combination of climate, human activity, and construction methods led to the limited number of surviving temples and mosques in Bengal.

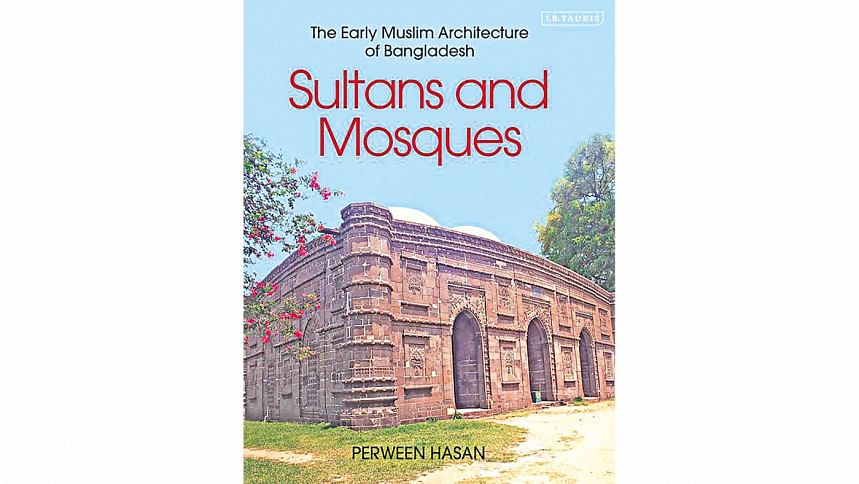

As I have elaborated in my book, Sultans and Mosques (paperback edition now available, Bloomsbury, I.B. Tauris, 2024), the domes of mosques and other buildings were low, lacking a drum, and minarets were largely absent. While minarets can be seen in structures like the Shait Gombuj Mosque, they were not as tall as those in Delhi, partly because limited communication meant that the call to prayer (azan) could not be heard over long distances. Minarets also symbolised the presence of Muslims in an area; their scarcity in this region also seems to be influenced by geographical factors. Villages, often accessible only by boat are almost invisible from the rivers due to the dense vegetation that surrounds them and seem isolated from each other specially when there are floods. Constructing tall minarets are unnecessary if they are not visible or if the azan cannot be heard from afar.

TDS: What is the historical significance of the mosques commissioned by the kings in this region, and what materials were typically used in their construction?

PH: Mosques built by kings or high ranking officials are usually larger, better built, and use higher quality or more expensive material. They are usually dated and therefore serve as a primary source of history. Their inscriptions and styles are also keys to the taste of the elite and often a clue to the particular identity that the patron chose to highlight. The Adina Mosque (1375) in Pandua, Malda district of West Bengal, India is a good example to illustrate this point. This mosque was constructed in the capital city by Sultan Sikandar Shah, an early independent sultan after he had twice defeated Sultan Firuz Shah Tughlaq of Delhi in battle. In the mosque inscription, Sikander Shah proudly referred to himself as the greatest ruler among the Arabs and Persians, with no mention of Bengal or India, making it clear that he sought to draw legitimacy from the central Islamic lands.

We know that brick was the traditional building material in Bengal. The massive structures at Paharpur and Mainamati were constructed with brick. As the region lacked natural stone, mosques built entirely of stone are rare. The Adina Mosque is the largest mosque in India and uniquely follows the classical Islamic architectural mosque plan of Western Asia. It is notable for its lavish stone facing. This uniqueness and identification with the well known style of West Asia was deliberate and the logic for choosing this style is borne out by the historical events of that time.

It is important to acknowledge that, in the early years, temple destruction was almost a consequential act following the conquest. As prominent religious symbols of a conquered people temples were the primary targets. This practice was not unique to Muslim rulers; destruction of temples of rival kingdoms and carrying away of images of patron gods as trophies was also know in pre-Muslim times in India. In the Adina Mosque, one notices how the external stone veneer has been sourced from Hindu structures. Similarly, many images of deities can be seen around the plinth of the Tribeni Mosque mentioned earlier.

Construction of mosques, specially a jami mosque was a very significant act for a Muslim king after the conquest of a new region. It symbolized a new presence and an authority which was established by reading the khutba (Friday sermon) in the new ruler's name. In many instances the king also served as the imam or prayer leader. Another significant act of a new ruler was the minting of new coinage bearing the king's name. The khutba also served to announce new laws and regulations, making the mosque a central place for public gatherings. Initial mosques were therefore often built using materials from destroyed temples, which not only provided ready material, but also reinforced the idea of the new building as a symbol of conquest.

A distinct feature of mosques in Bengal is the presence of multiple mihrabs, uncommon in other regions. The mihrab or niche indicating the qibla, is perhaps the only indispensable or key element in a mosque. Interestingly the earliest mosques in Islam from the time of the Prophet Muhammad (PBUH) did not have mihrabs. They were introduced into later mosques to indicate the place where the imam stood to lead the prayers. Even today it is often considered a specially sacred place as devotees place candles and incense inside the niche, although theoretically, in the absence of an icon every place in the mosque is of equal merit. The idea of multiple mihrabs in Bengal often placed opposite entrance doorways may have been a carryover from the structural element of niches in temples, where the sacred idol was placed inside a niche and was always opposite a doorway.

Over time, these foreign rulers recognized the importance of compromise and coexistence with the local population. From the fifteenth century onwards, this shift became evident as many non-Muslims were appointed to high-ranking positions in the royal cabinet. As foreign rulers, the sultans could not rely solely on the military force and officials from their native country as their numbers were limited, so collaboration with the local population became essential. Bengal, being geographically isolated and politically independent, faced repeated invasions from Delhi, and this constant threat significantly influenced the region's architecture and political dynamics.

A distinct feature of mosques in Bengal is the presence of multiple mihrabs, uncommon in other regions. The mihrab or niche indicating the qibla, is perhaps the only indispensable or key element in a mosque.

Maintaining independence was vital for the rulers of Bengal, as was the establishment of a distinct identity. Later Sultans actively patronized the Bangla language, leading to the translation of Sanskrit texts like the Ramayana and Mahabharata, as well as the writing of Mangal-Kavyas, the latter being highly integrative texts. Muslim writers who authored Islamic texts such as Rasul Charita and Nabi Vangsha (stories on the life and lineage of the Prophet) presented their works in ways that were deeply influenced by local culture. They narrated stories of the Arab world, including those of Fatema, Hazrat Ali, and the battles of Prophet Muhammad (PBUH), but told them in a setting that was familiar to Bengal, an environment replete with storms, cyclones, and tigers. For example at Hazrat Ali and Fatema's wedding feast people chew betel leaves as is customary in Bengal, and at the news of her husband's death, Fatema removed the vermilion from her forehead and broke her bracelets, traditional mourning practices in Bengal. Syed Sultan, who knew the original stories well, deliberately adapted them for the local audience. He explained that native Muslims were familiar with the Ramayana and Mahabharata but knew little about their own religious stories. To bridge this gap, he wrote these stories in Bangla, hoping that the Almighty would forgive him for his modifications. This mission became his life's work, with Nabi Vangsha being a very significant text of the punthi genre. We might not have known about these texts had it not been for the meticulous editing of the punthi manuscripts by the late Professor Dr. Ahmad Sharif published by the Bangla Academy, Dhaka.

TDS: Islamic civilisation is typically seen as city-centric, yet in Bengal, it has been predominantly rural. How has this been possible?

PH: The census of 1872, the first official one conducted under British rule shockingly disclosed that Muslims were more numerous in Bengal compared to other parts of India and that even within Bengal, its eastern part, the more rural one held the majority of the Muslim population. Richard M. Eaton ties this phenomenon to the predominance of agriculture in the eastern region; this in turn being related to the gradual eastward shift of the Ganges River. The creation of a fertile new delta made it more suitable for agriculture, while the western part where the capitals of Gaur and Pandua were located became relatively less productive agriculturally.

Eaton also attributes the large scale conversion to Islam in the east to the influence of pirs or spiritual leaders, described as "charismatic individuals" rather than strictly religious figures who came and settled among the rural agricultural communities. Many of them also spearheaded agricultural efforts, clearing forests or settling of land. For example, Khan Jahan Ali (d. 1459), the famous saint of Bagerhat is described in his tomb inscription as a military officer who defeated local Hindu kings, cleared the jungle, and constructed mosques. Subsequently he became venerated as a pir, pushing his original military identity as indicated by his inscription title of ulugh, to the background. These leaders inspired the local population to pursue agriculture and facilitated their conversion to Islam. Conversion was easier as the rigid caste system of Brahmanism was less prevalent in this region and there were many who followed cults of local deities. These individuals, already engaged in various agricultural activities, had more fluid religious practices and were more receptive to converting to Islam. Conversion too, was more of a 'cultural adaptation' than a radical change to a different and foreign religious order.

TDS: How did the architectural landscape in Bengal change during the Mughal period compared to the Sultanate period?

PH: While the Sultans were fiercely independent and fought every effort of take-over by the powers that ruled from Delhi, they patronized an architecture with a distinct regional identity. Contrarily, the Mughals, themselves an imperial power ruled the provinces from their north Indian capitals of Delhi, Lahore or Agra. Bengal under the Mughals was just another province or subah of the Mughal empire, albeit one that yielded the highest revenue to the imperial coffer. From an independent sultanate, it was reduced to provincial status. The marked difference in architectural styles between the Sultanate and Mughal eras springs from this change in status. The extant monuments of Dhaka, the Mughal provincial capital clearly bears allegiance to the architectural style of the capitals.

During the Mughal period brick continued to be the predominant construction material. This was in contrast to north India, where the the monuments were in a grand scale and the material, stone, red sandstone and marble. As an imperial power governing all of India from their capitals in the north, the Mughals maintained a consistent architectural style across their empire. So Mughal buildings everywhere even from the exterior are easily identifiable because of their plastered surfaces often broken into rectangular panels, high domes and imposing entrances. The lime plaster used in Bengal used to be polished to a shine to resemble the marble surfaces of imperial prototypes. It is significant that while mosques and other official architecture sponsored by the ruling Muslim elite followed the imperial Mughal style, contemporary temples opted for the Sultanate mode of the preceding period. So that the brick temples of this period stand in sharp contrast to Mughal mosques, palaces, gates and caravansaries. The brick and terracotta temples of Bengal have arched entrances, curved cornices and their exteriors are encrusted with terracotta panels depicting tales of the Ramayana and Mahabharata. Some continue to have the chala ceilings of Sultanate times, now covering the entire building instead of a particular part, while others have spires which usually hide a dome below.

TDS: Beyond royal and religious structures, what was the general housing situation for people in Bengal during the Middle Ages?

PH: Bengal was and still is primarily an agricultural society, with most people living in rural areas. Landownership was limited, and urban centres were few. Majority of the people resided in simple huts, and as noted by Niharranjan Ray in his seminal work Bangalir Itihas: Adiparba. the living conditions for the general population in Bengal remains largely unchanged over time. People lived hand-to-mouth, and their houses of clay were often vulnerable to decay from rain and wind. The architectural structures we have cited were exceptions as they were built with care and commissioned by influential individuals. While royal residences have not survived, historical accounts from foreign travellers describe some Nawabs (provincial rulers) residing in tents and wooden houses, which have not endured. In contrast, mosques and temples, constructed as places of veneration and with meticulous care, have lasted longer.

The interview was taken by Priyam Paul

Comments