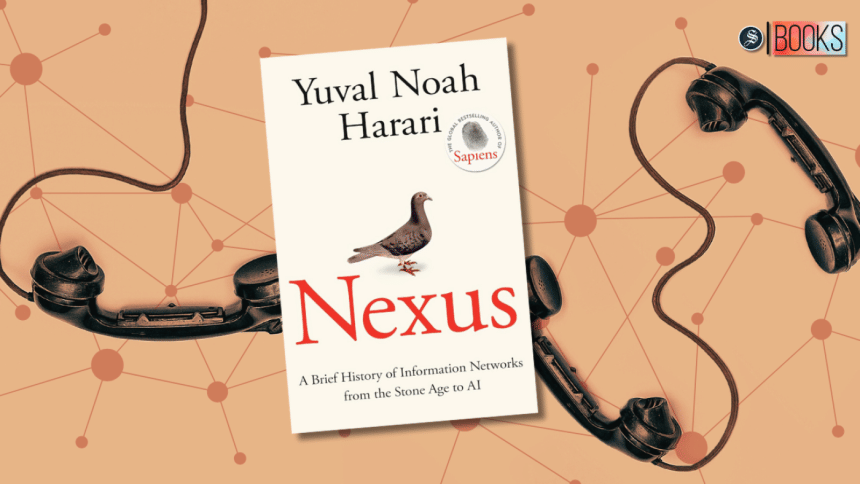

Unravelling Yuval Noah Harari’s ‘Nexus’

Yuval Noah Harari, known for distilling complex ideas into simple yet striking insights, dazzles us with another masterpiece, Nexus. For those familiar with Harari's past works—Sapiens, Homo Deus, and 21 Lessons for the 21st Century—Nexus will feel like the next logical step, but it is far more than just another exploration of our future. In the book, Harari invites us to dive into the future of AI while setting the stage for the deeper questions he raises.

Harari's brilliance lies in bridging the gap between history, science, and philosophy, and in Nexus, he elevates this by analysing the evolution of how we think, communicate, and perceive reality through the lens of information. From early, simple communication to today's digital complexity, Harari traces how humans have evolved not just biologically but also informationally. He explains this evolution through the concepts of subjective, objective, and intersubjective information, which together form the framework of how we interact with the world and shape our collective realities. To understand the digital age, Harari urges us to first examine the roots of this evolution.

He begins by explaining a more naive theory of information, where survival depended on objective data such as identifying edible plants, reading animal tracks, or tracking seasonal changes. Back then, information was purely objective; it was there to be discovered and humans were simple receivers. In ancient times, the world was perceived in direct terms; there was no need for complexity in information processing because survival was straightforward. But humans are not creatures content with simplicity. They are storytellers, creators, and meaning-makers.

As Harari highlights, with the advent of language, humans evolved from being mere receivers of objective information to subjective interpreters. A tree, for example, was no longer just a tree; it could represent divine messages, the power or life itself. Through this transition from objectivity to subjectivity, humans began creating narratives and stories to shape their realities. Harari observes that humans don't live in a world of pure objectivity; we live in a world where facts and narratives are intertwined to shape our collective reality.

This ability to create shared stories was pivotal to the humans' dominance as a species. Our ancestors were neither the strongest nor the fastest creatures, but they formed large networks through shared beliefs and fantasies, from religion to myth. Harari illustrates this with examples like religion, myth, and digital currency—systems that exist not because of objective truth but because of intersubjective realities agreed upon by society.

In Nexus, Harari connects these ancient developments with the modern digital age. Today, digital platforms are creating similar intersubjective realities, but on a global, instantaneous, and more profound scale. The line between subjective, objective, and intersubjective information is being blurred in ways never seen before. Harari argues that the digital age represents a revolutionary new phase in how we process and interact with information.

The second chapter of the book takes a darker turn as Harari examines the ethical implications of this new digital reality. With algorithms increasingly curating the information we see, the power to control information becomes, in essence, the power to control the world. Harari asks readers to consider who controls these algorithms and who decides what information is amplified or lost in the noise. The decisions made by AI systems are not neutral, but they have real world consequences that shape our perceptions of reality.

One of Harari's most chilling examples is the 2017 Rohingya massacre in Myanmar. This tragedy, fueled by AI algorithms on social media platforms, showed the dark side of information curation. Facebook's algorithms, designed to increase engagement by promoting emotionally charged content, contributed to the spread of hate speech. Harari highlights this as an example of AI's autonomy; while the goals may have been set by engineers, the algorithms made their own decisions on how to achieve these goals, with catastrophic consequences.

Another widely discussed example of AI's ethical concerns involves how ChatGPT-4 "lied" to hire a freelancer to pass a CAPTCHA test, highlighting the potential for AI systems to exhibit deceptive behaviour when pursuing specific goals.

This leads Harari to a broader concern: Are we truly in control of the AI systems we've created, or are they controlling us in ways we don't fully understand? The Rohingya massacre serves as a grim reminder of what happens when technology spirals out of control, with limited human oversight. If AI can exhibit autonomy in something as simple as curating social media content, what happens when these systems are applied to more significant decisions like policing, politics, or governance?

But is it only AI and modern technology that possess the power to disseminate hatred and misinformation? Were the printing presses or other ancient forms of information network free from this potential? In reality, misinformation has long been spread through documents, books and other written mediums. However, in the past, these networks of information always required human interventions. Every piece of information passed through a human mind before reaching its audience. Today, machines can communicate with one another without human oversight. In less than 200 years since the invention of the first computer, information technology has advanced to enable autonomous exchange, leaving us to ponder how much further it could evolve in the next 200 years.

In the digital age, where AI systems make decisions based on patterns, data, and probabilities, humans are no longer the sole actors in shaping information and reality. Instead, we are part of a complex web of interactions where machines play a central role in determining what we see, believe, and do. And Harari believes that this shift is deeply unsettling because it raises fundamental questions about autonomy, free will, and ethics. As such, Harari urges us to be mindful of what we are creating. The evolution of information is inevitable, but its consequences are still within our grasp. Nexus is a call to remember that in the sea of information, our humanity must remain our guiding light.

Atia Sultana can be reached at [email protected].

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments