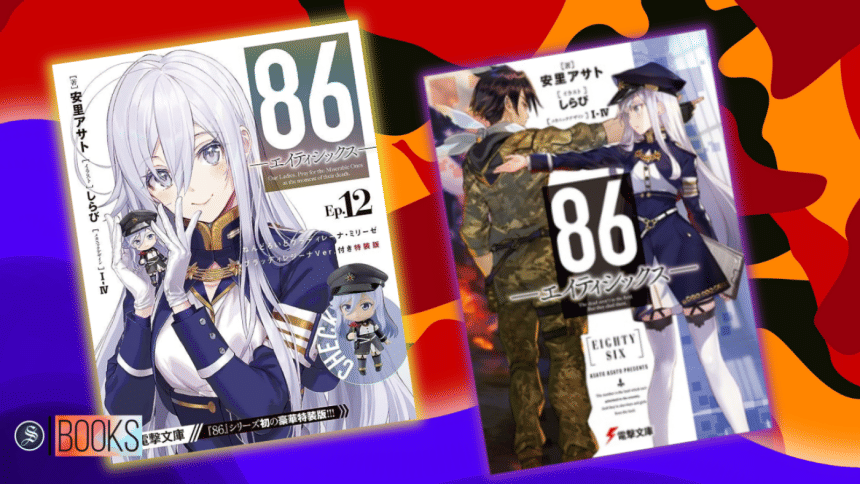

‘86 – Eighty Six’: How the light novel series depicts the humanity of dehumanised children

"No country would ever consider it an act of evil to deny a pig human rights. Therefore, if you were to define someone speaking a different tongue, someone of a different colour, someone of a different heritage as a pig in human form, any oppression, persecution, or atrocity you might inflict upon them would never be regarded as cruel or inhumane."

With these words, apparently taken from future memoirs written by Vladilena Milizé, the female protagonist of 86—Eighty Six (first published in 2019 by Yen On Press), writer Asato Asato (actual name: Toru Asakura) begins the first volume of her light novel series. Simple and definite, the words let readers pause and ponder, evoking the innumerable examples throughout history that correspond with them. They give us a taste of some crucial themes of this series—dehumanisation and, of course, the oppression begotten from the impunity it grants.

The story of 86 starts in a place called the Republic of San Magnolia, a democratic state built on the principles of equality and justice that had institutionalised the ultimate form of discrimination and injustice, perpetrating what can only be described as horrific genocide. The Albas, a race that makes up the majority in the country, has declared all minorities to be subhuman, forcefully sending them to fight a devastating war against the unstoppable mechanical legion that they themselves dared not fight. And since only "subhuman processors" are being killed in the fighting and not "human soldiers", propaganda spreads that it is a "war without casualties", even as adults die out and the children are drafted. The designation under which these minorities are grouped, 'Eighty Six', directly alludes to this extreme alienation: they are cast outside the 85 sectors of San Magnolia, where they are doomed to live and die.

I was first introduced to this light novel series by its anime adaptation, and my initial thoughts, based on the first few episodes, were that while intriguing, it wasn't going to be anything new. The themes of discrimination, genocide, and war were all topics that numerous great anime had dealt with in the past, and I failed to see how this one could have anything new to add. The characters, too, seemed nothing out of the ordinary at first. There is the Spearhead Squadron, an elite group of 'Eighty Six' soldiers who have survived the battlefield since childhood. There is Shinei 'Shin' Nouzen, their strong, silent leader. And there is Vladilena 'Lena' Milizé, an Alba major assigned to supervise them. She is also one of the few Republic citizens sympathetic to the plight of the Eighty Six.

However, some interesting events soon come to pass. Half way into the anime series, the surviving members of the Spearhead Squadron achieve freedom from the Republic's oppression. A few more episodes later, we learn that the Republic itself has fallen. Lena, despite being a fragile, soft-hearted person, builds herself into a capable and shrewd military leader who makes tough calls when necessity demands. Shin's tough façade is blown to smithereens as he fulfils his life's mission, leaving a traumatised child, and a self-destructive young man with a gaping hole in his chest. Even aside from the fighting and the romance, and even beyond the dehumanisation and genocide, the story had something interesting to say, and I couldn't resist checking out its source material. In the end, I was not disappointed.

86, the novel series, adds a lot more context to the Republic's racism, scapegoating of minorities for the nation's military failures, and genocide. But where the novels are truly at their most poignant is the exploration of the psyche of the children of genocide.

The books acknowledge that victims of atrocities are not automatically immune from perpetrating the same on others. Rather, it demonstrates that even among those who are oppressed, a larger group may still end up discriminating against those different from them, or scapegoating them for their predicament. It also shows how the oppressors may use these instances to justify and rationalise their own heinous crimes, claiming that they are only harming barbarians who hurt their own, and thus, deserve to be oppressed. At the same time, they give an empathetic portrayal of how honour and humanity can still survive through small and seemingly insignificant acts in the wastelands of death. How the slightest bits of warmth and kindness can penetrate through the frigidity of indifference and the scorching heat of cruelty. That even where there is no hope, not the slightest chance of there being a future where their humanity and existence are being denied, children still find ways to be children. "If you don't smile, you lose. If you don't have fun, you're just missing out," Kujo, a minor character, says. Giving into despair would mean losing to their oppressors, and so laughter and recreation become ineradicable acts of rebellion.

The key attribute of the characters' psychology that drives the story forward and makes it so thought-provoking for me is their pride. The pride of accepting life, death and every horror in between on the battlefield with a smile on their faces. Having lost everything, it helps them cope and make sense of the world. It gives them both a purpose and an excuse to cling to life and human dignity. This pride of being the reviled Eighty Six is what gives them salvation in a world where none seemingly exists. Reading the light novels, I often pondered—throughout war zones such as Palestine, Sudan, and Ukraine, is this how people feel?

86 does not romanticise or fetishise this pride. Rather, as the story goes on, the dangers of basing one's identity over such a concept is laid bare both for the readers and the characters themselves. Once the characters survive and move beyond the oppression of the Republic, internal struggles simmer within their hearts as the pride of dying on the battlefield clashes with the prospect of living beyond war. Their battles against the Legion take them to other parts of the world, and their beliefs and preconceptions are challenged time and again as they come into contact with different peoples and ways of life. In unexpected places, they see themselves reflected. They see different examples of what they could become, with some exposing their vulnerabilities, shaking them to their very cores, and others setting them alight with determination, offering hope. While much of the journey is still left, the characters have finally started to believe that there may be something nice beyond the thick mist.

These nuanced characterisations of those who have suffered terribly and are desperately trying to rebuild themselves are what have kept me hooked to the series. Whether Shin, Lena, and the rest would be able to actually move beyond the fog of their traumas; whether they would ever be free of the treacherous serpents of death that hide in every corner and shadow—these are all questions that the light novels have got me thoroughly invested in. And every time I read, it inevitably reminds me of those people who, every day in their own lives, face the same questions. To be able to do that, I believe, is one of the marks of a great piece of fiction.

Md. Nayeem Haider is a student of law and a contributing writer for The Daily Star.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments