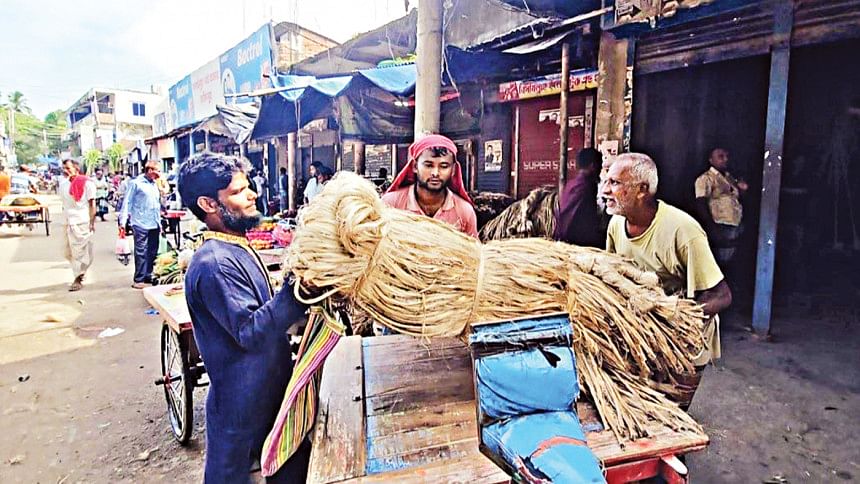

Jute prices jump amid supply crunch, polybag ban

Prices of raw jute, once dubbed the "golden fibre" of Bangladesh, have increased by nearly 19 percent year-on-year as demand has outpaced supply following the government's ban on polythene bags.

Farmers in key jute-growing districts say that punishing heat during the March-April plantation period devastated seed germination.

Besides, low prices in previous years discouraged growers from cultivating as much jute as before, reducing overall acreage.

As a result, raw jute production is projected to decline to around 7,574,000 bales (one bale is roughly 182 kilogrammes) in the current fiscal year, compared to 8,414,000 bales the year prior, according to the Department of Jute.

The government's decision to ban polythene bags in superstores from October and nationwide from November 1 further contributed to the price hike.

According to jute growers and traders, the finest quality jute now costs around Tk 3,800 per maund (37 kilogrammes), up from Tk 3,200 last year. Medium-quality jute prices also shot up by Tk 600 per maund to Tk 2,600.

Arifujjaman Chan, a jute trader from Kanaipur market in Faridpur, a major jute-growing district in Bangladesh, said raw jute is being sold for between Tk 3,200 and Tk 3,800 per maund, depending on quality and colour, compared to Tk 2,600-Tk 3,200 last year.

Mohammad Mahmudur Nabi, a jute trader in Pabna, another key jute-growing district, credited surging demand for the price increase.

However, many farmers could not fully capitalise on higher prices as they sold their produce soon after the June-September harvest period since they incurred increased costs for agri inputs such as fertilisers and labour.

Panchanan Das, a jute trader from Jamalpur Jute Market in Rajbari district, said only 10-12 percent of farmers currently hold jute stocks. The rest, he said, has already been purchased by small traders.

Isarat Matubbar, a jute grower from Chotto Bahirdia village in Saltha upazila of Faridpur, said most local farmers sold their jute immediately after harvest at low prices, only holding on to a few maunds for later sale.

Matubbar said he recently sold three maunds of jute at Tk 3,800 each, which had encouraged him to go for jute cultivation again next year.

Nabo Kumar Kundu, a farmer at Rautara village in the southwestern district of Magura, cultivated jute on five bighas of land (one bigha is 1,338 square metres) this year, yielding 50 maunds of raw jute, down from 96 maunds last year.

"Although yields decreased this year, fibre quality is much better," he said. "That is why we are getting good prices."

Zahid Sheikh, a 40-year-old jute grower from Hat Krishnapur village in Faridpur, said increased costs for fertiliser, irrigation and labour pushed cultivation costs to Tk 27,000-30,000 per bigha.

"This year, it cost us Tk 3,000 to produce a maund of jute. If prices remain at current levels, we can make a profit. However, if prices decline, jute cultivation in future will be difficult," he said.

Md Zahidul Islam, an assistant director at the Department of Jute in Faridpur, said farmers produced high-quality jute fibre this year, which commanded good prices.

Jahangir Hossain Mia, chairman of the Faridpur-based Karim Group, which owns a jute mill, said: "Mill owners want to ensure fair prices for farmers. If farmers receive fair prices, they will be encouraged to produce more jute. Increased jute production will enable mill owners to export jute products and keep mills running."

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments