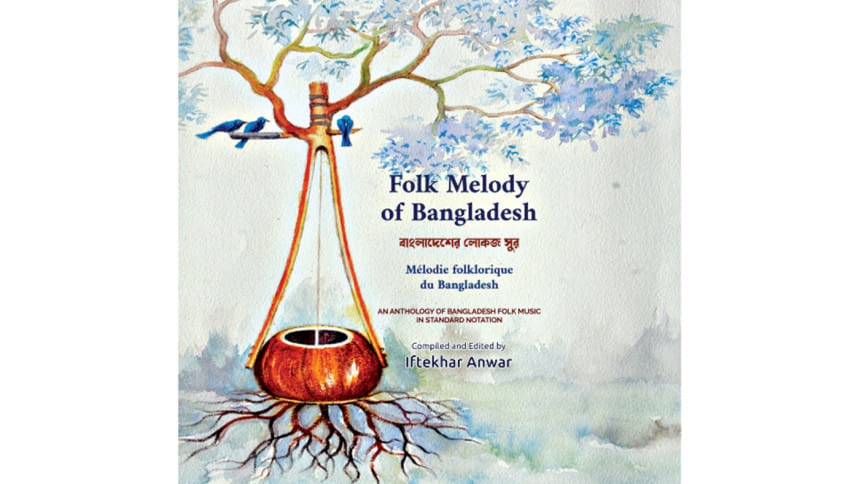

Taking folk melodies of Bangladesh to the world

Folk Melody of Bangladesh: An Anthology of Bangladesh Folk Music in Standard Notation is a music anthology that compiles 204 carefully chosen folk songs of Bangladesh that date from the 16th century. Iftekhar Anwar headed a team that compiled and edited the songs. The team presented the songs in staff notation with an international audience in mind. Alliance Française de Dhaka distributed the anthology as part of their 65 years of cultural cooperation between Bangladesh and France.

The dream started in 2004. Iftekhar was an undergraduate student in music at Arizona State University in the USA. He fostered two desires: First, how could he spread Western classical music in Bangladesh? Second, how could he spread the ethnic music of Bangladesh to an international audience?

Iftekhar returned to Bangladesh in 2009. The next year, he started the Classical Music Academy of Dhaka. As time went, his second desire became stronger. The stage for Folk Melody of Bangladesh was set in 2014. However, the journey required epic teamwork to compile an anthology for an international audience.

The anthology starts with testimonials, a preface, an introduction, acknowledgments, and a pronunciation guide. Chapter 1 introduces the reader to different folk music schools in Bangladesh, instruments, and stylistic conventions. The section on instruments describes folk instruments well enough that a person from another culture can identify which of their instruments could be a substitute. For instance, the dotara could substitute an oud in Arabia. Chapters 2 to 7 present folk songs based on regions. Chapter 8 includes one popular song, the origin and creator of which could not be confirmed. However, local sources acknowledged it to Harashnath Ganguly. At the end, there are Bangla lyrics, a glossary, and a bibliography. Some parts are presented in Bangla, while others in English and in French.

For the writer, the first hurdle was to identify the genres of folk music in Bangladesh. The team used the demarcation AKM Shahnawaz and Masud Imran identified based on ancient localities in their Manchitre Banglar Itihas (first published in 2011).

The second hurdle was the oral tradition through which tunes and melodies passed down from one generation to the next. Over time and space, pronunciations and dialects, choice of words, lyrics, and melodies have changed, so it was very difficult to verify the authenticity of many folk songs today. To address this challenge, the editorial team chose popular songs whose tunes and melodies have become canonical over time.

Based on the above, the anthology includes songs of giants like Fakir Lalon Shah, Hason Raja, Jasimuddin, Abdul Latif, Sheikh Bhanu, and Hemanga Biswas. The anthology also includes songs of lesser giants. This made the anthology broad in its perspective.

The third hurdle was identifying a reference tune. Where possible, the team relied on official recordings. This included recordings of Abbasuddin Ahmed, Sachin Dev Burman, Abdul Alim, Amar Paul, Hemanga Biswas, Nirmalendu Chowdhury, Farida Parveen, Rathindranath Roy, Chandana Majumder, Kiran Chandra Roy, Momtaz Begum, Nina Hamid, Sayeem Rana, Shamarin Dewan, and others. In other instances, the team visited different shrines and places where popular tunes have been preserved over generations.

The fourth hurdle was to present songs to an international audience. Standard staff notation can express notes, pitch, and tempo. It can also tell the reader how to perform a tune. Folk songs in Bangladesh evolve around four (or five) popular taals. These taals, presented through time signatures, were: 3/4 (Dadra, Jhumur), 4/4 (Kaharba), 5/4 (Jhaptal), and 7/4 (Teora). The tempo (loy) was presented through BMP (beats per minute) or through Prestissimo (quick tempo).

The second hurdle was the oral tradition through which tunes and melodies passed down from one generation to the next. Over time and space, pronunciations and dialects, choice of words, lyrics, and melodies have changed, so it was very difficult to verify the authenticity of many folk songs today.

The next hurdle was determining notes and their duration within each bar. This took time. The team repeatedly listened to identify the correct notes and their durations inside each bar in reference to the chosen signature tune.

The staff notations were presented in a single layer. They are suitable for vocals and instruments that emphasise single notes like that of a bansuri. For string (guitar) and reed (piano) instruments, additional layers can be added by musicians.

Where possible, each staff notation presentation included the name of the composer and/or lyricist, with their birth and death years, and which part of Bangladesh they originate from. The team also mentioned the source of the recordings with a short description of each song.

The next challenge was language. The team used the International Phonetic Alphabet (IPA). The IPA broke down each word, syllable by syllable, to bring out nuances of the language. This was synchronised with the notes.

The final question—how could the team be sure that non-Bangla-speaking people would be able to pronounce Bangla with relative accuracy? A group of musicians from Columbia University performed two songs in a vocal and instrumental orchestration. Their performance gave confidence to the team that a non-Bangla-speaking audience can pronounce and perform Bangla folk tunes using the anthology.

The presentation of folk songs of Bangladesh in staff notation is not unique. Khandaker Nurul Alam went to what was then West Pakistan to learn notational music and compiled some folk songs in staff notation. However, they lacked academic depth. The notation was not suitable for performance in orchestration. This is where Folk Melody of Bangladesh stands out.

For the first time, Folk Melody of Bangladesh presents an anthology of folk music in Bangladesh in standard staff notation with IPA. It will now be possible for non-Bangla-speaking people to sing the lyrics and perform with instruments in orchestration. It can be an academic exercise, as well as a journey into a rich cultural heritage. The anthology is also a starting point for others to spread the folk tunes of Bangladesh to a global audience.

The writer of the book, Iftekhar Anwar, is the founder and director of Classical Music Academy in Dhaka; the academy has its chamber orchestra.

Asrar Chowdhury is a Professor of Economics at Jahangirnagar University. He is a music enthusiast and freelance contributor to The Daily Star. Email: [email protected].

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments