A wake-up call for Bangladesh to reform its healthcare

India's visa restrictions on Bangladeshi nationals, while initially perceived as a barrier, could serve as a wake-up call for Bangladesh to strengthen its healthcare system and regain the confidence of its patients.

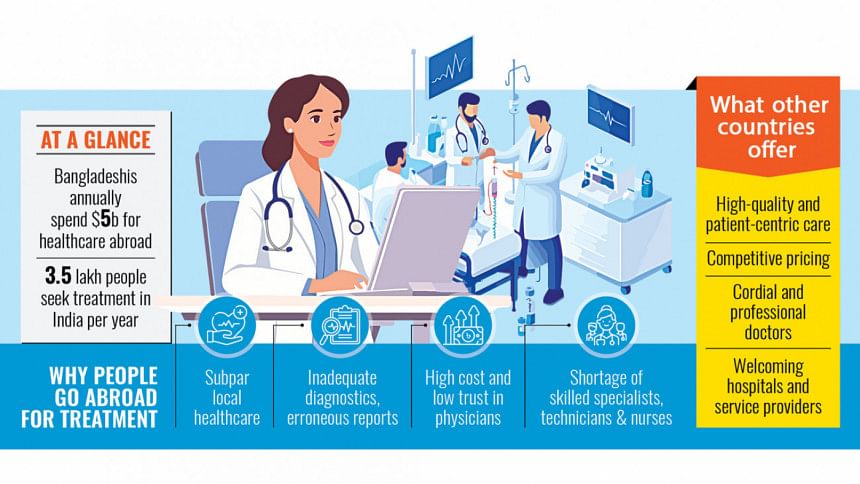

With as many as 3.5 lakh Bangladeshis seeking medical treatment in India annually, the restrictions offer a unique chance for local providers to address systemic issues and retain patients who would otherwise travel abroad. Experts urge Bangladesh's health authorities to rise to the occasion and rebuild trust among its citizens.

This systemic overhaul is especially urgent given the personal struggles of individuals like Sanjida (not a real name), a Mirpur resident, who faced a critical health challenge in 2020. After undergoing surgery at Dhaka's Green Life Hospital to remove an ovarian cyst, her biopsy reports delivered devastating news: she had cancer. Advised to start chemotherapy, she followed her oncologist's recommendation for additional tests, only to realise that the tests she had completed earlier had been overlooked. It became apparent that her doctor's approach was perfunctory at best. Terrified and disillusioned, her family decided to seek treatment abroad.

Sanjida travelled to Mumbai's Tata Memorial Hospital, where doctors reviewed her medical history and conducted fresh diagnostics. They concluded that the surgery in Dhaka had been incorrect. With an appropriate operation, her cancer could have been addressed earlier. After another surgery and three rounds of chemotherapy in Mumbai, she returned to Dhaka. Today, she takes regular medication and visits India every six months for follow-ups. Reflecting on her ordeal, Sanjida laments the inattentiveness and unprofessionalism she experienced in Bangladesh's medical system, contrasting it with the care she received in India.

"Even with the high cost of living and transportation, Indian hospitals are more affordable and trustworthy than those in Dhaka," she said.

Sanjida's story is not unique. Retired government officer Shahidur Rahman, 69, sought cardiac care in 2019 after experiencing chest pain. Diagnosed with three heart blockages at two leading hospitals in Dhaka, he was advised to undergo stent placement. Sceptical, Shahidur travelled to Bengaluru to consult Dr Devi Shetty, a renowned cardiologist. Additional tests revealed no blockages, and he was prescribed medication instead. Since then, Shahidur has lived without chest pain and has lost faith in Bangladeshi healthcare providers.

A CRISIS OF CONFIDENCE

The healthcare industry in Bangladesh is dominated by the private sector, which has seen significant growth in tertiary hospitals and diagnostic centres.

The stories of Sanjida and Shahidur are emblematic of a deeper issue -- a healthcare system grappling with a crisis of trust. On the surface, Bangladesh's healthcare infrastructure appears robust. The country boasts 566 public hospitals, which include 37 state-run medical colleges providing hospital services, and around 5,000 private medical facilities. Private sector investment has led to the growth of tertiary hospitals and diagnostic centres, creating an illusion of progress. Yet, beneath the numbers lies a stark reality: many Bangladeshis still feel compelled to seek treatment abroad, believing that local facilities cannot meet their needs.

The reasons for this exodus are manifold. Experts point to rushed consultations, diagnostic errors, steep treatment costs, and a perceived indifference from medical professionals. Many patients complain of being treated like mere numbers -- hurried through appointments with little to no time for questions, clarification, or reassurance. This lack of a personal touch often proves just as alienating as the more tangible deficiencies. In contrast, some patients argue, India has built a reputation for offering not only medical expertise but also a level of care that feels holistic and humane.

Bangladeshi patients primarily travel to India for cardiology (14 percent), oncology (13 percent), gastroenterology (11 percent) and other complex issues, according to a 2023 study published by the National Library of Medicine. The same report found that India's healthcare infrastructure -- including skilled specialists and comprehensive follow-up care -- attracts an estimated 3 lakh to 3.5 lakh Bangladeshi patients annually. Kolkata, Chennai, Vellore, and Mumbai are the most frequented destinations.

"Bangladesh's healthcare system lacks sufficient skilled physicians and technologists, especially for complex diseases like cancer and organ transplants," said Rumana Huque, a health economist and professor at Dhaka University. "While we have capable doctors, they are overstretched and unable to provide the level of care patients expect."

Bangladeshis spend over $5 billion annually on medical treatment abroad, with India and Thailand as top destinations. Yet, Huque emphasised, many of these expenses could be curtailed if local healthcare providers improved their practices.

Tamzeed Ahmed, a clinical and interventional cardiology specialist at Evercare Hospitals Dhaka, observed that the past two to three months have seen an uptick in patients seeking consultations in India. This trend persists despite India's visa restrictions.

Meanwhile, Md Esam Ebne Yousuf Siddique, chief operating officer of Square Hospitals, highlighted the uncertainty surrounding the long-term impact of these restrictions. He noted that, over the last three years, Square Hospitals has not recorded any significant fluctuation in patient numbers, suggesting that the effects of visa restrictions on local healthcare utilisation may still be unfolding.

SYSTEMIC CHALLENGES AND PATIENT DISSATISFACTION

Patients often cite Bangladesh's under-resourced diagnostic facilities and dismissive medical culture as significant deterrents. Even private hospitals equipped with advanced technology struggle due to a lack of trained personnel to operate it effectively.

Syed Abdul Hamid, a professor at the Institute of Health Economics, Dhaka University, pointed out that poor diagnostic accuracy, inadequate consultation time, and indifferent behaviour from medical professionals erode trust. "Doctors in India excel in patient communication, providing detailed explanations and emotional support. This starkly contrasts with the rushed consultations typical in Bangladesh," he said.

During the Covid-19 pandemic, when international travel was restricted, Bangladeshi patients had no choice but to rely on local healthcare providers. Many received quality care, proving that the country's medical system can deliver when adequately supported. However, the lasting perception of neglect and inefficiency continues to push patients abroad.

CALLS FOR REFORM

Industry leaders acknowledge the gaps. AM Shamim, founder of Labaid Hospital, admitted that while Bangladeshi doctors are technically skilled, they must improve their bedside manner and spend more time with patients. "We have the capacity to treat complex illnesses, but patient trust is eroded by behaviour and insufficient consultation time," he said.

Similarly, Prof Md Moazzem Hossain of Aichi Medical Group called for systemic reform. "We need skilled technologists, uniform cost structures, and better regulation from the Directorate General of Health Services," he said. "Patients need to feel confident in their care, and hospitals must prioritise patient-centred service over immediate profits."

India's visa restrictions, while inconvenient, offer Bangladesh a rare opportunity to reflect and reform. It's a chance to rebuild confidence, invest in patient-centred care, and address the systemic flaws that push patients abroad. Without addressing these issues, experts warn, the country risks perpetuating a reliance on foreign medical services -- a dependency both costly and avoidable.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments