Why graffiti containing the word 'Adivasi' faces reluctance in Bangladesh

The recent decision by the National Curriculum and Textbook Board (NCTB) to remove the graffiti that contain the word "Adivasi" from the back cover of the Grade 9 and 10 Bengali Grammar and Composition textbook underscores the successive governments displaying an apparent aversion to officially recognising the term. This reluctance is not a mere oversight but a calculated stance rooted in historical, constitutional, and socio-political complexities. It seems that the usage of the word has become a contentious issue.

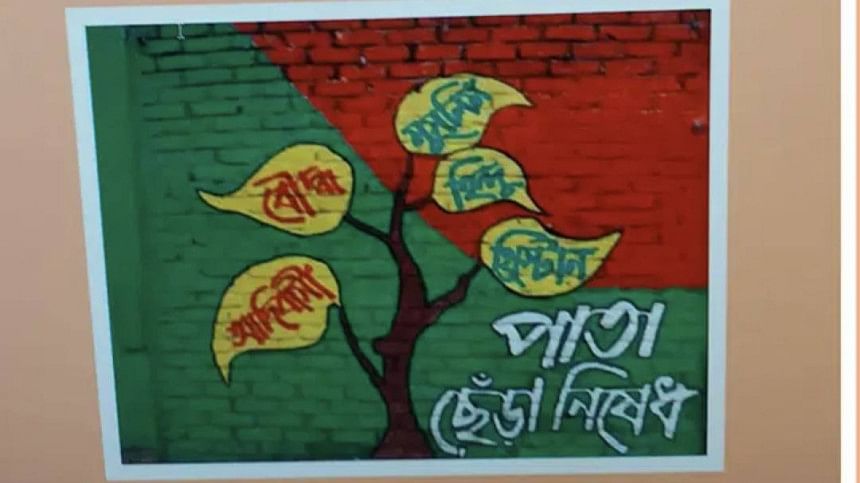

The graffiti on the textbook symbolised a broader movement against discrimination, advocating for the rights of marginalised communities, including Adivasis. Its removal, following pressure from groups like "Students for Sovereignty," reflects a deeper unwillingness to confront systemic issues affecting these communities.

The graffiti featured in the textbook -- a powerful symbol of anti-discrimination -- served as a rallying point for students advocating for equality and justice. Its removal sends a troubling message: that the government is unwilling to stand against discrimination and instead prioritises appeasing groups that continue it. This act of erasure not only undermines the struggles of Adivasi communities but also weakens the broader movement for social justice in Bangladesh.

The graffiti is the part of people's uprising. Changing or removing it is an act of disrespect to the July uprising. If any group speaks against it, their true intentions need to be exposed.

The graffiti symbolised the diversity, pluralism, multi-religious, multilingual, and multi-ideological identity of Bangladesh and the message of the graffiti was one of the achievements of the uprising. We cannot let that achievement go to waste.

One of the primary justifications for avoiding the term "Adivasi" is grounded in the Constitution of Bangladesh. The Constitution refers to ethnic groups as "small communities" or "tribes," deliberately avoiding the word "Adivasi." Proponents of this terminology argue that recognising these groups as "indigenous" could imply certain rights and privileges under international frameworks, such as the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP). Official recognition as "Adivasi" would necessitate addressing longstanding issues of land rights, autonomy, and cultural preservation—obligations that the government may find politically inconvenient.

This pattern is not new. In 2009, the then-government led by Sheikh Hasina gave a message but later the very government said that there were no "Adivasis" in the country.

Over the years, successive administrations have demonstrated a similar reluctance, often citing constitutional limitations while sidestepping the moral and ethical implications of denying the existence of these communities.

A certain group often frame the recognition of Adivasis as a threat to national sovereignty, arguing that it could encourage separatism or foreign intervention. By aligning with these groups, governments seek to maintain political stability, albeit at the cost of marginalising vulnerable communities.

The refusal to recognise Adivasis has far-reaching implications. It perpetuates a cycle of marginalisation, denying these communities access to basic rights and resources. By failing to acknowledge their identity, the government also undermines the rich cultural diversity that is integral to the nation's heritage.

Moreover, this denial risks alienating Adivasi communities further, fostering resentment and deepening divisions within society. It contradicts Bangladesh's commitments to international human rights standards and tarnishes its image as a progressive nation.

The continued reluctance to embrace the term "Adivasi" is emblematic of a broader unwillingness to address the structural inequalities faced by indigenous communities in Bangladesh. While constitutional arguments and political calculations may provide convenient justifications, they fail to address the moral imperative of ensuring justice and equality for all citizens.

Recognising Adivasis as indigenous is not merely a matter of semantics; it is a crucial step toward rectifying historical injustices and building a more inclusive society. The government must move beyond symbolic gestures and take concrete actions to uphold the rights and dignity of these marginalised communities. Only then can Bangladesh truly claim to be a nation that values equality, diversity, and justice for all.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments